Lost in the Borders Between Cultures

Writers count themselves lucky to be born with even a single obsession. Philip Roth and Raymond Carver, Eudora Welty and William Faulkner are, or were, all monomaniacs--hedgehogs, in the famous formulation of Isaiah Berlin--who have learned to do one thing and do it very well. So what should a reader make of a writer who sinks her teeth into good old-fashioned American topics like carnies and abortion clinic demonstrators, and then sets not one but several stories in Muslim Malaysia? Is this versatility what Sir Isaiah meant by a “fox”?

In her first book of stories, Kim Edwards displays a variety of talents, not the least of which is her ability to jump geographies. Indonesian peasants, American fire eaters and French acrobats insinuate their stories into Edwards’ book, often to great effect. Sometimes her characterizations are hammered thin, as in one teatime tale in which an old-school colonial wife is shown how little she knows her adopted country by the arrival of a fresh, American girl.

Yet Edwards rescues many stories with a brave determination to extend their lives beyond their natural endings and beyond cliche. “The Great Chain of Being” tells of Eshlaini, the oldest daughter of a Muslim family. As each of her siblings is born, her father bestows upon them a second name, an ancestral name that replaces the name given by her mother, a name that fixes each sibling in character and in time. The last to receive her new name, Eshlaini’s story seems to end with the drama that leads her father to finally turn his naming eye on her and determine her fate. And it would be a fine story if Edwards had chosen to end there. But Eshlaini’s life continues, building without twisting to an ending that is even more powerful and certainly more unusual.

Ultimately, one suspects that Edwards, like Somerset Maugham in an earlier day writing of England with one hand and South Asia with another, has colonized a variety of experiences to create her personal empire of stories. And like Maugham, she is at heart a hedgehog, even if she’s dressed up like a fox, obsessed in her own creative and ruminative way with the borders between cultures.

In the best of her stories, that border is a frontier of language. “Spring, Mountain, Sea” recounts the marriage of Rob and Jade, he a Navy translator, she a peacetime war bride he has brought back from Asia to small-town America. Stymied by the language of Twain and the recipes of Betty Crocker, Jade retreats into the cocoon of her own tongue. Defeated by his wife’s exoticism and his town’s Masonic ordinariness, Rob learns how to lie in two languages. As each of their three children is born, he promises Jade that the English names he has given them are direct translations of the elemental Spring, Mountain and Sea she has chosen.

The power of the story, and of Edwards’ best writing, comes ultimately from its ability to cross another border, from the merely multicultural to the universal. Like a fox patrolling the perimeter, Edwards knows the only hope of reconciliation comes from “the power of words to soothe or build or comfort.”

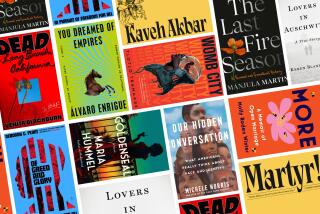

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.