Wallet Disney

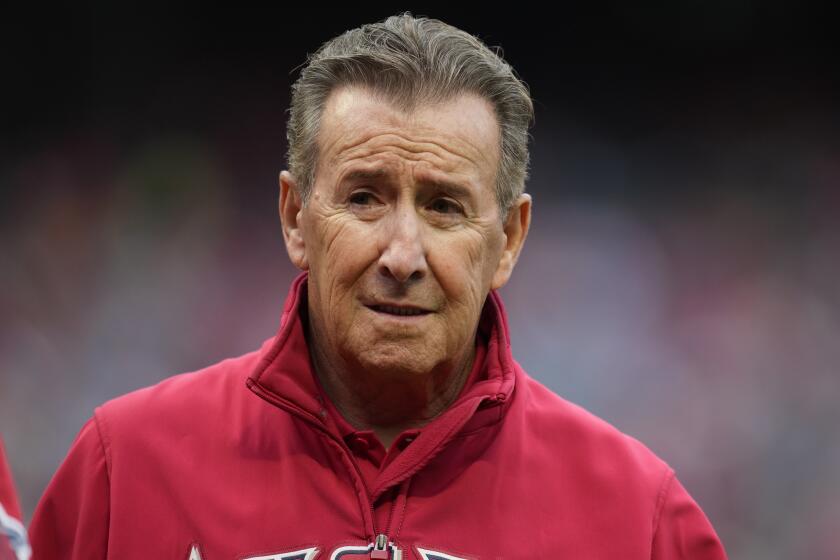

Terry Collins managed the Houston Astros in 1996, when the Walt Disney Co. bought the Angels and stuffed the baseball team into a tiny corner of the company portfolio.

Drayton McLane, the Astros’ owner, was a grocery salesman. A rich and successful one, to be sure, but still a grocery salesman. McLane would now compete against Disney, one of the world’s most visible corporations, one that recorded a $2-billion profit last year.

“In Houston, we had one guy telling us an individual owner couldn’t compete with the corporations,” Collins said, “so we thought they’d spend a lot of money.”

Agents drooled and owners panicked when mighty Disney strode into the brave new world of professional sports, but not until Wednesday--six years into the lifetime of the Mighty Ducks and almost three years into its management of the Angels--did the company make a free-agent splash in either sport.

Disney dug deep, very deep. In just the kind of move McLane and other owners feared--and fans cheered--the Angels signed first baseman Mo Vaughn to a contract that guarantees him $80 million over six years, the highest average annual value in major league history.

Why now?

Mickey Mouse is not allergic to spending vast sums. Disney paid $19 billion to acquire ABC/Capital Cities, but the company did not consider bidding $19 million for free agents like Roger Clemens, the dominant pitcher the Angels so desperately coveted two years ago, or Ron Francis, the talented center who could have joined the Ducks’ Paul Kariya and Teemu Selanne this year and formed the most devastating line in the NHL.

So why now, at four times the cost?

“People think Disney just decided to spend some money. They didn’t,” Angel General Manager Bill Bavasi said. “They’ve never been afraid to spend the money, as accused.

“There’s a change in action, but not a change in philosophy. We just haven’t seen the players we thought were the right fit for the right type of money. If we had seen a player like Mo Vaughn last year, he would have been signed. That’s easy to say, but that’s the truth. Players like this don’t come around very often.”

Before Bavasi could sell Vaughn on the Angels, he and Disney sports chief Tony Tavares had to sell Chairman Michael Eisner and the rest of the corporate posse in Burbank on Vaughn.

To Disney, Vaughn is Selanne with a bat. Although the Ducks have yet to sign a major free agent, they acquired a superstar in his prime when they traded for Selanne in 1996. They subsequently extended his contract by two years and $19.5 million.

Selanne, a former kindergarten teacher in his native Finland and the “First Godfather” to the national children’s hospital there, works tirelessly with kids and charities that benefit them. Vaughn, a community icon in New England, envisioned and developed the Mo Vaughn Youth Center near Boston.

Vaughn, like Selanne, embraces leadership not only on the playing field and in the community but in the locker room as well, a personality package Bavasi stressed in a seven-page recruiting pitch to Vaughn.

“If you could read the letter he had written to me, along with the deal he had offered, you could tell what kind of people he was looking for,” Vaughn said.

“You could see Disney was looking to put itself in position to win. They wanted talent with attitude. Disney really wanted to spend some money to get some attitude.”

Attitude doesn’t pitch, though, and the Angels need a top starting pitcher. They needed one two years ago, but they refused to bid for Clemens, a five-time Cy Young Award winner. They needed one last year too, but they passed on the ace of the 1997 market, Darryl Kile. So now Disney pulls an $80-million rabbit out of its hat?

“Right or wrong, maybe we had concerns with Clemens about his age,” Bavasi said. “Right or wrong, maybe we had concerns with Kile that he had had just the one strong year. Our judgment is that this is a special guy.”

Granted, but what about Randy Johnson, the Angels’ remaining target? Vaughn and Johnson each marked the 1998 season by feuding with ownership on a bumpy ride to free agency, but Vaughn hit 40 home runs, batted a career-high .337 and powered the Boston Red Sox into the playoffs.

Johnson grew so disenchanted in Seattle, posting his worst season this decade (9-10, 4.33 earned-run average), that Manager Lou Piniella finally told him he ought to pitch better so the Mariners could trade him. While Vaughn never shirked from his role as team leader and spokesman, Johnson typically shrugged off the media and once scuffled with teammate David Segui over the volume of the clubhouse stereo. The next day, the emotionally charged Johnson shut out the Angels, striking out 15.

“He can’t pitch better than that, which makes you wonder where it’s been all season,” Piniella said after the game.

Yet Disney stands ready and willing to pay Johnson the same $13 million per season now committed to Vaughn, albeit over four years, not seven. Disney wants to win. The Angels need an ace. Johnson would be that ace.

Bavasi invested prudently in long-term contracts for a core of young stars. The Angels finished second in the American League West in 1995, second in 1997, second again in 1998. In the absence of big-time, big-ticket help, this is a second-place team, and no longer a young one.

“This act has pretty much worn thin,” pitcher Chuck Finley said in September. “The song is getting a little sour. I sense patience running out around here.”

When respected veterans like Finley and shortstop Gary DiSarcina wonder about ownership commitment, Disney takes note. When the novelty of the renovated Edison Field wears off and the tease of competitive teams wears thin, Disney acts.

“What puts fans in the seats is a winning ballclub--not a competitive ballclub, but a winning ballclub,” former Angel president Richard Brown said.

During the 1995-96 transition from Autry family management to Disney management, Brown consulted extensively with Disney officials.

“They expressed some concern about spending money,” Brown said.

“I think it’s just an educational process. They came into the industry, and they acted as responsibly as they could. But the teams that have won since they’ve been in have been the Marlins and the Yankees. Both had extraordinarily high payrolls.

“It’s a poker game. The stakes are high. If you want to stay in, you have to bet.”

On the day the Angels signed Vaughn, the industry took notice, inside and outside the Angel offices.

Said Dodger General Manager Kevin Malone: “It shows they really want to try to win. They’re doing what they feel they need to do.”

Said Collins, now the Angel manager: “Is Disney ever going to spend money? Guess what? It’s been spent. And it’s been spent wisely, on as good a talent as there is in baseball.

“I think that gives our organization--and Disney-- tremendous credibility within our industry.”

The Ducks may never take a seat at the free-agent poker table. The disparity between the highest team payrolls and the lowest team payrolls is nowhere near as great in the NHL as in major league baseball, and the correlation between team payroll and team success is nowhere near as pronounced.

In addition, while baseball players achieve free agency after six seasons, regardless of age, hockey players must wait until age 31. By that time, Kariya would have completed 12 seasons in the NHL, in a sport far more grueling.

But Kariya’s contract expires after this season, and Disney almost certainly will raise his salary from $8.5 million to $10 million or more.

At Wednesday’s news conference, the first question asked concerned Tavares’ infamous 1997 statement: “I don’t think anybody is worth $10 million.” Tavares did not attend the news conference and declined comment later, but Bavasi fielded the question smartly.

“If I walk up to you and ask you if somebody’s worth $10 million to play baseball, you might say no,” Bavasi said. “But the current market is what it is, and we are players in this market.”

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

The Money Is Flowing

Largest guaranteed contracts in Angel history:

$80 Million (6 Years); Mo Vaughn, Signed Nov. ’98

$22.5 Million (4 Years): Tim Salmon, Signed Feb. ’97

$18.5 Million (4 Years): Chuck Finley, Signed Dec. ’91

$16.05 Million (3 Years): Ken Hill, signed Nov. ’97

$16 Million (5 Years): Mark Langston, Signed Dec. ’89

$15.5 Million (4 Years): Bryan Harvey, Signed Dec. ’91

$14 Million (3 Years): Mark Langston, Signed Feb. ’94

$12 Million (3 Years*): Chuck Finley, Signed Jan. ’96

$11.7 Million (4 Years): Gary DiSarcina, Signed June ’96

$11.4 Million (3 Years): Chili Davis, Signed May ’95

$11.4 Million (4 Years): Gary Gaetti, Signed Jan. 91

* An option year since has become guaranteed, raising the contract value to $17.8 million over four years.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.