IN OLD VIRGINIA, A PRESIDENT REVEALED

MOUNT VERNON, Va. — I was admiring a pair of white silk breeches that once belonged to George Washington when the museum curator offered this tidbit of information: The Father of Our Country didn’t wear underwear. For men in 18th century America, it seems, a long shirt did the trick.

My guide on this behind-the-scenes visit to the National History Museum in the capital went on to point out Martha Washington’s corset, describing how, during the hot, humid Virginia summers, she cast it aside and went about the house in loose-fitting gowns.

Whoosh! In those few startling moments, all the dust blew off the Washingtons. They stood before me as never before, two living people.

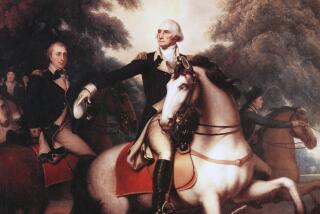

Now we are in the year of the bicentennial of Washington’s death, in which he is being presented in exhibitions and events not just as military hero, farmer, businessman and president, but also as a lover of fun, dancing and the ladies, to whom he often wrote poems in his youth.

I live in northern Virginia, where the heritage of Washington’s era is familiar, a backdrop of daily life. When warmups to the bicentennial year began, I decided to try looking at some key spots in our first president’s life with fresh eyes.

I started with the bicentennial’s traveling show, “Treasures From Mount Vernon: George Washington Revealed,” in New York, which travels to the Huntington Library in San Marino in spring (March 16 to June 6). And I confess that I was surprised by its forthrightness in presenting Washington the man. One of the first objects to greet me was a pair of Washington’s famous dentures, made not of wood as many people believe, but of lead, wire, human teeth and cow and elephant teeth carved to size. No wonder his lower lip juts forward in his likeness on the dollar bill. Looking at the dentures, you wonder how he ever managed to open his mouth, much less chew.

Concentrating as it does on personal items and anecdotes involving them, the exhibit breathes life into the general, as he was called even by members of his family. There are examples of his remarkably well preserved clothes, for instance. Standing about 6 feet 3, he was, by his own admission, “pretty long in arms and thighs.”

From her own clothes on display, it is plain that Martha made an ample, if short, companion. Her voluminous bathing dress, sewn of checkered homespun, adds yet another detail to private life in that time and place: The ankle-length dress has a lead-weighted hem, a precaution taken to keep it from ballooning up in the water of the mineral springs Martha occasionally visited.

Much taken with the humanity of the material, I found myself increasingly charmed by the explanatory labels, many of which contain quotes from family members, friends and associates. They shed quite a bit of light on Washington’s relations with the opposite sex. One female contemporary, the wife of a colonel, writing to a friend, reported that the general could be “downright impudent at times--such impudence, Fanny, as you and I like.” A fellow officer was amazed when at a party Washington danced with the man’s wife for three hours “without once sitting down.” A gentleman at another ball remarked that the general danced every dance, “that the ladies might get a touch of him.”

My favorite label suggests that Washington had an earthy sense of humor. It contains a quote from a letter that he sent to an old colonel who had just taken a new wife: He suggests that to satisfy her, the officer should “review his strength, his arms and his armament,” then “make the first onset . . . with vigor that the impression may be deep if it cannot be lasting or frequently renewed.”

For visitors to the exhibition who have never been to Washington’s home, there is a 10- by 6-foot model of the mansion at Mount Vernon. Its exterior walls slide open to reveal all of the interior, including rooms on the third floor rarely seen by the public because of difficulty of access. Created on a 1-inch-to-1-foot scale, it is furnished with exact miniatures of hundreds of the Washingtons’ belongings, right down to the candlesticks.

While the traveling exhibition brings Washington and his world amazingly close, there is nothing quite so exhilarating as actually visiting sites he knew in his beloved Virginia, many of them little changed in two centuries. For this bicentennial year, the state has developed five driving tours that follow his footsteps through different periods of his life (see Guidebook), beginning with the 250-year-old town of Alexandria, which he helped lay out as an assistant surveyor when a youth, and winding up at Yorktown battlefield, on which he defeated the British in 1781.

My wife, Liet, and I began our own little tour in Fredericksburg, another charming town filled with 18th and early 19th century buildings, about an hour’s drive south of Washington, D.C.

Our first stop was the modest clapboard house that Washington bought his widowed mother, Mary, in 1772. Her sundial still marks the hours in the garden, and “her best dressing glass”--a mirror made of silvered tin to avoid the glass tax imposed by the British--continues to reflect the light of day in her bedroom.

George’s only sister, Betty, lived nearby at Kenmore Plantation, a Georgian-style mansion filled with exquisite antiques. It also boasts two of the most superb molded plaster ceilings in the United States--so beautiful that Betty’s husband arranged, at Washington’s request, for his “stucco man” to go to Mount Vernon to execute the plasterwork that graces the formal dining room to this day.

Travelers without the luxury of time would do well to pursue only one or two of the state-recommended tours, however interesting these might be, and concentrate their energies on Mount Vernon, which is just 13 miles south of Washington, D.C., and accessible by public transit from the city.

Our first president’s estate is, curiously, not a government monument; it is maintained by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Assn., which purchased it in 1853.

This year, the mansion has been given a special freshening up, and it looks more like what it was when Washington died here in his bed on Dec. 14, 1799, than in all the intervening years. Beginning this week, more than 300 items related to the Washingtons’ life here will be displayed in the house, 102 of them on loan from private and institutional collections.

Liet and I spent a day at Mount Vernon in December, and the excitement among the staff was almost palpable as they prepared for the big year. Our enthusiastic guide on the house tour had a great name, Nancey Drinkwine. As she escorted us about, she proudly revealed that she would be Abigail Adams during the bicentennial year, one of several “first-person characters” who, in period attire and well versed in the lives of the historic people they represent, will tell stories about the house’s occupants and the furnishings.

The first room we entered was the green, two-story-high, formal dining room, added to the mansion by the general to accommodate the ever-growing number of guests eager to be in his presence. Even as we stood there, the room was receiving its final touches for the bicentennial, with a restorer on a scaffold minutely applying green paint around the delicate Wedgwood-like white plaster reliefs garlanding the upper walls. Light poured through the massive Palladian window onto an enormous rectangular table set for dinner, with a big meat pie (a plaster replica) on a platter placed in the middle. Such a pie, according to the original recipe (which visitors can pick up in the kitchen, a separate building), would have contained a boned goose, turkey, fowl, partridge and pigeon, the smaller stuffed inside the larger, surrounded by chunks of hare, woodcock “and what Sort of wild Fowl you can get,” baked in a crust prepared from a bushel of flour and six pounds of butter.

Though the Washingtons entertained often--in 1798 alone, they had 700 overnight guests--they did not own a large dining table; instead, they set out trestles and planks, which could be covered by cloths and easily dismantled when the meal was over, presumably to make room for the dancing the general so enjoyed.

To go from this elegant chamber to the main hall, we had to step outside onto the columned piazza, which functioned as an extra room during the hot summer. Sitting on the Windsor chairs that graced the shaded terrace, the Washingtons and their guests could take the air and look across the lawn to the sweep of Maryland countryside on the other side of the Potomac River, a stirring view that remains unsullied to this day.

The broad hall also provided relief from the heat when the doors on the west and east fronts were left open and the warm air was drawn up the stairwell and out the cupola on the roof, creating a breeze.

Washington’s study, on the south side of the house, served as his inner sanctum. He could go there from his bedroom directly above by private staircase, wearing, perhaps, his checked dressing gown (included in the traveling exhibition) and minus, I would imagine, his dentures. Alone, he could shave at a dressing table, then get down to business with his secretary. He owned 70,000 acres of land, 8,000 of which made up the Mount Vernon estate and adjacent farms, which he inspected almost daily on horseback.

The general was an enterprising farmer, using advanced scientific methods. A replica of the 16-sided round barn he designed for efficient threshing has been erected in a dell on the grounds.

We viewed the study as it has been presented over the years--a tidy place, leather-bound books on shelves behind glass-paned doors, desk unlittered, one chair in front of it, another chair with fan attachment, activated by a pedal to create a breeze, drawn up to a window. But as we learned from Nancey Drinkwine, the truth was otherwise: The general kept the room crammed with papers, books and such assorted items as saddles, a tool chest, dental equipment, eight swords, seven guns, four pistol braces, one telescope and 11 “spy glasses.” For the bicentennial year something of that happy disorder will be recaptured, with books and papers piled high.

The study will look as Washington might have left it the fateful December morning he went out into snow to work on a project and caught his death of a cold. Suffering from an acutely sore throat that was constricting his breathing, the dying man was bled three times by the doctors attending him in his bedroom. As if that weren’t enough to weaken him and lower his resistance further, imagine the effect of their other treatments: getting him to drink molasses, vinegar and melted butter; forcing him to vomit; bathing his throat in ammonium carbonate; having him gargle with vinegar and sage and then inhale a steam of hot vinegar, all before giving him a final enema. He died saying, “ ‘Tis well.”

We happened to be visiting Mount Vernon on the very day that marked Washington’s death at the age of 67. His bedroom had been arranged to look much as it had been then, with the bedcovers pulled back and various instruments, bowls and towels scattered about. As luck would have it, we were invited to participate in the dry run of a mock funeral procession that will be a regular activity throughout the bicentennial year. A spooky visual presentation called “Washington Is No More,” complete with flickering candles, lugubrious music and mournful first-person accounts, will be shown several times a day in the greenhouse. And a reenactment of the funeral, with reconstructed coffin, cavalry and infantry, cannons, a riderless horse, solemn music and mourners, will wind up the year of commemoration on Dec. 18, the anniversary of Washington’s actual interment.

As our second guide, Sandy Newton, explained to our small group, Washington’s death occasioned an outpouring of grief such as the nation has rarely seen since. The bell of the Presbyterian Meeting House in Alexandria, as just one example, tolled for four days without stopping. With our guide in the lead, Liet and I walked the route the body took from the dining room, where it had lain for three days in strict accordance with the general’s wishes (he had an inordinate fear of being buried alive and wanted everyone to be certain that he was truly dead and not comatose), to the old family tomb, located in a grove of trees overlooking the river.

After visiting the “new” tomb to which the Washingtons’ remains were moved in 1837, Liet and I wandered down the path to another special place, the forested grave site of many of the slaves Washington owned, marked now by a simple truncated column set in a stone circle. Through their labors, these men, women and children made life at Mount Vernon possible. Washington knew this, and it bothered him, as leader of the Revolution that had yielded the country liberty, that many Americans remained in bondage. By the terms of his will, he set his slaves free, arranging for the older ones to receive pensions. There can be no knowing just who lies beneath the thick-trunked oaks that have sprung up there. But it is a place where silence rings loud in the ears.

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

GUIDEBOOK

In Washington’s Footsteps

Getting there: United and American fly nonstop from LAX to Washington’s Dulles Airport. Fares start at $256.

Getting around: The Washington Flyer bus runs every 30 minutes, 5 a.m. to 11 p.m., from outside the main terminal at Dulles to downtown Washington; $16 one way, $26 round trip. Telephone (888) WASH FLY, or (703) 417-8417.

Mount Vernon, tel. (703) 780-2000, is open daily, including holidays, 8 a.m.-5 p.m. April through August; 9 a.m.-5 p.m. March, September and October; 9 a.m.-4 p.m. November through February. Admission is $8.

Information about driving, public transportation and tours from Washington is available at the Mount Vernon number.

Where to eat: The Mount Vernon Inn, which is on the grounds, serves fair fare; there’s also a cafeteria.

Where to stay: Alexandria’s Old Town is full of 18th century charm and is worth a visit itself. Thirty-one Old Town residences offer rooms with private bath, $85 to $150 for a double, including breakfast. They can be booked through Princely Bed & Breakfast Ltd. in Alexandria; tel. (800) 470-5588.

For more information: A free booklet listing George Washington bicentennial events and driving tour itineraries is available from Virginia Tourism Corp., tel. (888) 828-4787. Information also is available on the Internet at https://www.VIRGINIA.org.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.