Managed Care: You Get What You Pay For

Whether Americans’ future health care is provided by the private managed care system or a single-payer government system, it is plain that there will be limits on what is reimbursed.

But at this point much of the public does not seem ready to accept such limits. There is tremendous resistance, with people sometimes going as far as to file claims circumventing the restrictions through subterfuge.

Two cases that came to my attention this past week both illustrate what seem to be unrealistic expectations of an HMO by patient and, in the first case, an employer.

In both cases, complaints were made against Health Net, the state’s fifth-largest managed care firm, with more than 2 million clients enrolled.

In the first case, I received a copy of a Feb. 9 letter regarding an upholsterer, Armando Hernandez, sent to Health Net by Peggy Radle, office manager at the Gardena furniture manufacturer Martin Brattrud.

“As you know, Mr. Hernandez had emergency surgery while visiting in Mexico on Sept. 30, 1998,” Radle wrote the HMO. “It is now nearly 4 1/2 months later, and after countless phone calls and correspondence sent to your staff, you now are apparently asking for information which could have been requested 4 1/2 months ago.”

The Hernandez claim with Health Net, for nearly $1,700, was that after months of fruitless visits for rectal pain to the Mullikin Medical Center in Long Beach, he had been on a trip to Mexico when an emergency arose. He had surgery that corrected the problem.

When I phoned him, however, Hernandez told a somewhat different story.

Over many months, he said, he had been unable to see his primary-care physician, seeing a physician’s assistant and two Mullikin emergency doctors instead, and finally he had decided to go to Mexicali, 230 miles from Los Angeles, and see a Mexican specialist.

He said this specialist immediately performed surgery, removing a benign tumor. He had paid the doctor out of his savings and was now seeking reimbursement from Health Net, which contracts with Mullikin to treat its members.

Hernandez said his employer had warned him “not to tell the insurer I went to Mexico for a consultation or it might not pay me, to say I was there on vacation.”

The human resources director at Martin Brattrud, Nanette Davis, confirmed to me that she had advised the subterfuge, feeling that unless this was a clear emergency, Health Net would refuse payment, viewing it as an impermissible departure from its network of doctors.

Two practitioners with Mullikin, surgeon Sandy Witzling and Randee Willis, the physician’s assistant, both insisted to me that Mullikin gave Hernandez satisfactory treatment. Witzling, who has seen Hernandez four times since he returned, said that Hernandez had not had a tumor removed in Mexico but had had surgery on an abscess and come back with an infection.

Ron Yukelson, a spokesman for Health Net, said that if Hernandez felt he had been inadequately treated at any time at Mullikin, he should have reported it to Health Net and it would have taken action.

Franklin Tom, corporate counsel for Health Net, observed: “Under an HMO network, you need to stay within the network. An emergency situation . . . would be a different thing altogether.”

In other words, if a Health Net member goes to China and comes down with appendicitis, Health Net will pay for surgery there. But it probably won’t pay if Hernandez crosses the Mexican border to get treatment he could have gotten in the network here.

Still, Health Net is not saying definitely that it won’t reimburse Hernandez. Instead, it is asking for medical records from Mexico showing that an emergency existed on the day he had the surgery.

Yukelson also noted that Health Net has other, more expensive plans that would allow a patient more leeway to leave the network and still be entitled to at least some reimbursement.

I can’t help but feel it is vital for all to realize that you may be able to get what you pay for in managed care, but probably not more.

The second Health Net case involves a young schoolteacher from Monrovia, Laura Kiker.

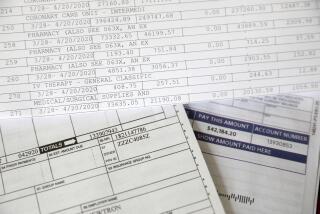

Health Net paid $45,000 for surgery at UCLA Medical Center after Kiker suffered five years of back pain, complicated by a snowboarding accident.

But she was dissatisfied by postoperative therapy within the Health Net network at the Pasadena Rehabilitation Institute and sought payment for therapy at the more expensive Michael Fortenasce and Associates, outside the network.

Health Net declined to authorize this, but it offered her therapy at a network facility in Pomona, 20 miles away, which Kiker said was too far for someone in her condition to drive on her own. She acknowledged having made a recent 400-mile trip to Fresno and back but said she did not do the driving.

More recently, in a Feb. 8 letter, a Health Net case coordinator, John Cregan, said that the HMO would make no more payments for therapy because it “is not medically necessary.” He said an outside review agency had upheld the denial (although apparently without any input from Kiker).

Cregan told Kiker she could appeal, but the point may be moot, because even if Health Net were to authorize more therapy based on pleas by her doctor, Duncan Q. McBride, that she continues to have significant pain, there is an impasse over where it would take place.

Kiker told me that she could join a PPO, with many more treatment options, but that it would cost her $2,400 more a year, plus a 10% co-payment for each doctor visit. This compares with $187 a month she pays now, plus a $5 co-payment for each authorized medical visit.

Again, I’m afraid, if you can afford more under the current system, you can get more treatment options.

Ken Reich may be contacted with accounts of true consumer adventure at (213) 237-7060 or by e-mail at ken.reich@latimes.com.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.