MISSING PIECES

What he wants, what he needs, is right there in front of him. Eye level. So close he could almost reach out and grab it.

It’s almost as if it were 15 feet in front of him, down a clear path, with everybody watching.

Inhale. Exhale. Bend the knees. Cock the wrist.

Win an NBA title.

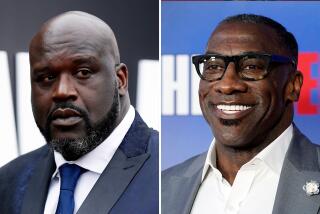

Only for Shaquille O’Neal could destiny seem tangled up in something so ordinary and something so sublime.

All he’s being asked to deliver is the easiest thing, and the hardest thing: Make free throws, carry the Lakers to a championship.

Pretty much everything in between, he has already done.

“It’ll happen one day,” O’Neal said when asked if he feels a desperation to win a title. “If everything works the way I’m planning, it’ll happen.”

Then he smiles, and adds in a typical O’Neal deadpan, “If not, I’ll be a bum. I’ll be the worst big man ever.”

It is hardly, of course, that drastic, but close enough to stop his laughter fairly quickly.

Two weeks into his eighth NBA season, and O’Neal is playing a more complete game than ever before.

At 27, he is in shape, at his peak, inflicting his will upon opponents at both ends of the floor, eagerly devouring the advice and cajolery of his new coach, Phil Jackson, who came to the Lakers primarily for the chance to work with O’Neal.

His relationship with Kobe Bryant has warmed, to the point where they have at times taken adjacent lockers for road games and can jokingly play one on one sometimes after practice.

His offense has expanded to include some short-range jump shots and he has, so far, fit willingly and cohesively into Jackson’s passing-oriented triangle system.

But O’Neal, a career 53.6% free-throw shooter, is also worse than ever at the line, painfully wrestling each shot to the basket, despite hours of practice, thousands of shots and nightly debate in the postgame locker room and on the talk shows.

“It’s just going to be a growth thing, and the sooner we attack the problem from the real cancer and start working on chemotherapy on this thing--if I can take this allegory a little bit farther--the better off we’re going to be,” Jackson said. “Because he’s going to make progress during the course of the season.

“Might as well face it now, early in the year, and have it not be a problem in the playoffs.”

O’Neal’s nightly failures at the line, though, have come to represent all of his shortcomings, all of his frustrations, and all of the expectations the NBA-watching world places on a 7-foot-1 mammoth with fast feet, explosive legs, and a good-natured disposition.

Each miss seems like a piece of the same easy story--giant can do things no one else can, giant has obvious weakness that prevents him from being an end-game force, giant never reaches mountaintop--and only O’Neal himself can change it.

By making free throws. By winning championships. They are the great agony and the great promise of Shaquille O’Neal. How could they seem so much the same?

He was ejected twice in a recent four-game stretch, once for shoving back after absorbing hard fouls, once for fighting with Charles Barkley after Barkley threw the basketball at his head.

Jackson suggests that the drumbeat of foul after foul--especially the successive games in which Dallas Coach Don Nelson sent players to foul O’Neal intentionally--and question after question about missing free throws has created a growing tension and, perhaps, a lower free-throw percentage.

Dale Brown, O’Neal’s coach at Louisiana State and an enduring mentor, says he too has noticed something.

“I find him to be a little more agitated than ever right now,” Brown said from Baton Rouge, La. “That agitation, I think, is maybe due to the fact that he is being fouled heavy and also that so much is expected of him because of the money and the things that he has.

“I think what he feels more than anything is perhaps that he’s getting fouled so much. . . . The same thing happened here. It almost took the fun out of the game for him in college.”

The Goliath Story

As he starts what figures to be the peak period of his career, after physically dominating the league for seven seasons without having the team and the chemistry to win a championship, O’Neal says he expects to play eight or nine more seasons, plenty of time to develop all sorts of new career paths and story lines.

But for now, he can compare himself to nobody else in history, except one: Wilt Chamberlain, who dominated his smaller, weaker foes, but did not win a title until his eighth NBA season, when he was 30.

Who struggled with his free-throw shooting his whole career.

Who died last month, causing O’Neal some amount of reflection.

“Wilt’s death, he took it kind of personal,” said O’Neal’s friend and bodyguard, Jerome Crawford. “I think he understood Wilt’s philosophy and it’s starting to maybe wear in.”

Said O’Neal, “I don’t know what kind of life he led, but the big guy, nobody feels sorry for you. That’s fine. That’s life. If you’re good looking, the girls like you, then you just have to accept it. . . . “

Brown says that he brought the teenager into his office when O’Neal was leaving LSU after his sophomore season and cautioned him about the fate that awaited him.

“I said, ‘Until you win an NBA championship, and that’s almost impossible for anybody, you will be the modern day Wilt Chamberlain,’ ” Brown recalled. “It’s never the guards and the little guys who get that. It’s always the biggest big center.

“Shaquille is the most generous, most happy-go-lucky guy you’ll find. But that’s never portrayed. He’s always this huge, tough guy. Maybe some of that’s his fault. Maybe he doesn’t want that side of him to be portrayed. But he’s a gentle giant. I think maybe Wilt was the same way.”

And somehow, maybe that is part of being Goliath in the NBA: You act ferocious or opponents might think they can get away with anything. You are treated as if you’re invulnerable. Along the way, you miss free throws.

“There’s no comparison with anyone else in the league,” Houston Rocket center Hakeem Olajuwon said before a recent matchup with O’Neal. “Nobody’s like him. . . . He’s only like Wilt, but of our time. You have to compare apples with apples.

“I think with Shaq, it’s just a question of time. I think he’s going to get there eventually, no question. He knows, for example, for myself, it was 10 years. He knows there’s a price to pay.”

Said former Bull center and current assistant coach Bill Cartwright, a key part of Jackson’s first Chicago title run: “Winning a title is not an individual thing, it’s a team thing. Certainly, there’s no question that with the right combination of people around him, especially with the coach that they have now, they’re going to win and they’re going to win big.

“I think that’s more of a thing for Jerry West to say, ‘OK, now we have this force, this Wilt Chamberlain Jr., so let’s get him some people around him.”

Michael Jordan himself didn’t win a title his first six seasons in the league, veteran Laker big man John Salley points out. Not until Jordan was surrounded with a deep and talented supporting cast, and not until Jackson installed the triangle and a winning atmosphere did the Bulls take off.

To measure O’Neal by the number of rings won, at this point, may not be fair to him or the league.

“Look at the history of the game,” O’Neal said. “Talent means nothing, except for that [1980s Magic Johnson, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar-led] Laker squad. All the other squads that won it didn’t really have a lot of talent, they just had teamwork.

“Aren’t I right about that? The Lakers had a lot of talent. But Chicago had Jordan and [Scottie] Pippen and guys you never even heard of. Guys you look at on paper, you’ll kill them. . . .

“San Antonio, they’ve got one or two players and a ton of role players. Talent doesn’t work all the time. Maybe we’ve had too much talent. Too much salt in the soup is not good. Just enough salt is perfect.”

Which is where Jackson and his staff come in. And where the Lakers’ roles become more clearly defined and more precisely followed.

O’Neal’s teams have been swept out of the playoffs four of the last five seasons--twice with the Lakers, twice with Orlando, where once it was by Jackson’s Bulls. Jackson suggests that means that when matched against a foe with an answer for O’Neal, his teams have had no ability to adjust.

“I think Phil knows I’m a team player, that’s why he came here,” O’Neal said. “If he thought I was arrogant and didn’t want to listen, I don’t think he would’ve come.

“I knew he was going to be a hard-nosed guy. I knew he was going to come with a winning attitude, and he was going to change our attitude. I was ready for that.”

Jackson, for his part, says he never thought about O’Neal’s reputation for going through coaches--he has had five in eight seasons.

“You know, it never even occurred to me,” Jackson said. “Maybe it’s just confidence on my part, that I don’t look at that as a factor with this player.”

Foul Play

The crisis of the moment, of course, is not related to coaching.

The issue is O’Neal’s 34.9% free-throw percentage, how it affects his game, and what that means for a team that expects to move deep into the playoffs.

Brown mentions that O’Neal’s huge hands make it hard to set up properly with the ball, and that O’Neal did make them more regularly in college during a brief, aborted trial period shooting underhanded, though O’Neal begged Brown to allow him to shoot regularly instead of “granny style.”

Crawford says O’Neal will haul him to an outdoor basket to grab rebounds, day and night, and that O’Neal can be quite consistent.

Jackson says O’Neal must shoot with more arch. O’Neal says he can’t understand, he makes them in practice.

“Don’t ask me dumb questions,” O’Neal bristled recently, when asked if he believes opponents might continue to try to provoke him into retaliating.

But a few days later, after the Lakers had beaten Phoenix to go 7-2, and 6-0 in games he was around to finish, O’Neal quietly said that both losses were “100% my fault” and volunteered that he knows his free-throw shooting must get better.

It’s right there in front of him.

“I know if I want to get to the big dance, if we want to win it, I’m probably going to have to hit those shots,” O’Neal said. “And I will.”

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

Free-Throw Percentage

Shaquille O’Neal’s free-throw percentage per year compared to the league average.

More to Read

All things Lakers, all the time.

Get all the Lakers news you need in Dan Woike's weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.