From Musty Maze to Crown Jewel

LONDON — For more than 5 million people each year, a visit to the British Museum meant a trek through parked cars and chaotic crowds, around a forbidden central courtyard and along byzantine corridors to locate--with the help of a map--number-coded rooms filled with treasures from the world’s great civilizations. It was a challenge for the hearty, a nightmare for the faint of heart.

Not any longer.

A three-year, $150-million renovation of the British Museum unveiled by Queen Elizabeth II on Wednesday has turned the musty 19th century labyrinth into an urban landscape, pleasing to the eye as well as the heart, and a fitting crown to a year of millennium cultural projects in London, including the stunning Tate Gallery of Modern Art.

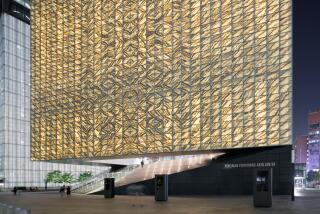

Gone are the cars from the British Museum’s frontyard, replaced by landscaping. Inside, the museum’s two-acre Great Court (which has been dedicated to the queen) has been cleared of a clutter of book stacks and covered with a monumental glass roof, a latticework of triangles designed by Lord Norman Foster that reveals passing clouds and, occasionally, sunlight.

The Reading Room--the focal point of the Great Court and a workplace for great English-language authors ranging from Charles Dickens to W.B. Yeats, as well as for philosophers such as Marx, Lenin and Gandhi--has been refurbished and opened to the general public for the first time in 150 years.

And throughout the vast, bright, marble-tiled courtyard, studded with ancient sculptures such as the 300 BC Turkish stone lion of Cnidus, are steel pillars bearing clear directions. No more numbered rooms. No radar required to find Egyptian mummies and the Rosetta Stone. Instead, there are signs and arrows indicating the way to African, Asian, British and other European art and artifacts. Suddenly, the museum is larger, more open and accessible, and the Great Court is the hub.

Critics have been awed by the overhaul.

“It has out-Louvred the grand Louvre in Paris,” wrote Hugh Pearman in the Sunday Times Magazine. Comparing Foster’s roof to I.M. Pei’s glass pyramid at the Paris museum, he added: “The British riposte . . . is just as radical, even more ingenious and . . . arguably more dramatic.”

The Daily Telegraph’s Richard Dorment called the Great Court “the most surprising, and most sensationally beautiful, space in London.” His colleague at the paper, Giles Worsley, added that “it will be a dull visitor who does not stop for a moment, transfixed by the looming image of the Reading Room and the oscillating curves of the new roof.”

The Ravages of Time and of a Growing Collection

It may be hard to imagine getting so worked up about a roof--but this one is an 800-ton, three-dimensional sculpture made up of 19 miles of steel and 3,312 glass panels, each cut into a unique triangle, all coming together in a high-tech swirl around the green copper dome of the Reading Room and above porticoes’ classic Ionic columns to create the largest covered plaza in Europe.

“Everybody who walks through there says, ‘Wow,’ ” museum director Suzanna Taverne said in front of a newly restored entrance.

The British Museum was designed by Sir Robert Smirke in 1823 as a stone quadrangle, with a series of porticoes surrounding a garden. Home to the museum and British Library, the four-wing building was soon bursting at its seams. Five years after its completion in 1850, the Reading Room--designed by Smirke’s younger brother with a cupola wider than the one at St. Paul’s Cathedral--was added to the courtyard, slightly off-center.

But books spilled out of there too, into temporary shelters erected in the courtyard, which evolved into a maze of alleys. Over time, the buildings blackened with grime, and the dome of the Reading Room cracked and crumbled to the point that librarians often scrambled to cover books with sheets of plastic against falling raindrops and bits of plaster. And a dingy gray entrance hall colored the atmosphere in the British Museum, which, designed for 100,000 visitors annually, nonetheless drew more than 5.5 million a year to its fabulous collection.

Radical action was required. After much agony, the decision was made to move the British Library to its own quarters, which was done in 1998. Foster & Partners won the bid to renovate the museum with engineering firm Buro Happold, a job paid for by about $67 million in National Lottery funds for millennium projects and the rest in private donations.

“We came up fairly early with the idea of covering the courtyard,” Foster said in an interview in the Reading Room. “And with the idea that this space, even though the British Library had moved, should continue as a library. So many people have passed through here, it is so steeped in history. And the British Museum is a receptacle of learning.”

The design, he said, “is a combination of responding to the old but not being intimidated by it, of confronting it and building on it.”

In came the cranes and excavators, the workers with hammers and drills to erect the computer-designed roof, refurbish the Reading Room and rebuild the south portico torn down long ago. New gallery spaces, a theater and educational center have been added along with museum shops and cafes that are discrete enough not to look like a mall.

The Glitch That Stonewalled the Project

Like many of this year’s millennium projects, this one had its controversy. The Millennium Dome in Greenwich was a flop and will close at the end of the month. The Millennium Bridge--also designed by Foster--to link the city of London with the Tate Modern across the Thames River wobbled so much on opening it was immediately closed and must undergo a multimillion-dollar reinforcement.

Asked if the museum roof, naturally expanding and contracting in the elements and mounted on sliding bearings, would sway, Foster said sheepishly, “It has to move. We hope it moves in the right way.”

The problem at the British Museum was with the rebuilt south portico, the main entrance to the Great Court. It was supposed to be covered in English Portland stone, but halfway through construction it was discovered that the contractor had substituted a less expensive and slightly paler French limestone.

“It was straightforward deception,” museum director Taverne said.

English Heritage, a preservation group, and other arbiters of taste were called in for consultations and agreed not to pull down the work that had been done. The facade of the new south portico is a lighter color than the others, but then it is 150 years newer, Foster noted. Some payment was withheld, and the case may go to court.

The drum-shaped Reading Room, meanwhile, was covered in a bright Spanish limestone. Inside, the blackened windows were replaced by clear glass, through which the 19th century stone facades and 21st century glass-and-steel roof are visible. The interior of the dome was gilded and repainted in its original eggshell and pale-blue colors. Its book-lined walls and blue-leather desks remain, to be supplemented by 50 computers with access to a vast art database.

A seemingly endless list of names of the great poets, novelists and thinkers who used the room is inscribed on the wall: T.S. Eliot, Aldous Huxley, Rudyard Kipling, George Orwell, Virginia Woolf. It looks like a temple of learning illuminating the Great Court at the heart of the museum.

“The Great Court truly lives up to its name,” wrote Jonathan Glancey in the Guardian newspaper.

Many critics say it is the crowning achievement of Foster’s distinguished career, which includes reconstruction of the Reichstag in Berlin and the Hong Kong International Airport.

Foster is not ready to throw in the towel on his career or to rush to judgment on the British Museum.

“You can do all of the simulations on computer, the studies of wind tunnels and lighting, but in the end it is all about the senses, the way it sounds, the way it feels. In the end you have to wait until the crowd arrives,” Foster said.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.