A Formula for Disaster in Irvine School Funding

When Irvine school trustees voted early this month to strip nearly $5 million from next year’s district budget, it was after several months of dire warnings that the cuts would be inevitable if Irvine residents refused to levy a new parcel tax on themselves.

Three months after the measure failed, the cuts are a painful new reminder of an unusual predicament that lies buried deep in the Irvine’s sleepy, undeveloped past: The state pays this wealthy suburban community about $100 less per student than the average district in California receives.

“The reason that Irvine gets less is because 25 years ago we were bean fields and tomato fields and orange groves,” said Irvine PTA activist Leslie Alden Crowe.

Crowe’s explanation covers half of the equation for school funding disparities that exist statewide, and even among otherwise similar districts in Orange County. Simply put, a community’s healthy tax base doesn’t automatically translate into more money for the local school district.

The other half of the complex state funding equation lies in a year-old program under which the state rewards districts with historically poor attendance rates if they are able to cut absences. Districts like Irvine with very good attendance had nothing to gain, further widening the funding gap.

The difference between the state average and what Irvine receives for its 23,000 students comes to roughly $2.3 million, almost half the amount of the recent budget cuts which will devastate the district’s elementary science, art and music programs, increase class sizes and slash the number of guidance counselors, nurses and school librarians.

It’s enough to set school officials’ blood boiling.

“If the revenue limits were set today . . . does anyone doubt that Irvine would have a higher tax base per student than Garden Grove or Santa Ana?” asks Paul Reed, Irvine’s deputy superintendent for business services.

Yet both those districts--less affluent than Irvine--won by a longshot in the last school year: Garden Grove by about $38 more per child and Santa Ana by more than $46 per student. The best-compensated school district in the county last year was Los Alamitos Unified, which received $4,490 per student. Irvine got $4,189.

The state average was $4,287 for unified school districts, those which include elementary through high school. Elementary districts receive an average of $4,116 and high school districts, $4,947.

The current school-funding policy dates to 1972, when the state overturned the system by which cities had funded their school districts.

A new system that was seen as more equitable was put in place: The state collected a share of the money counties took in from property taxes, and then divided that money up among school districts according to funding formulas.

The court ruling that led to this change created so-called revenue limits--a ceiling on the amount of money each school district can receive per student. This was seen as a way to prevent some districts from being flush with funding, while others struggled financially.

The limits were set based on what the communities were spending on education at that time. In the early 1970s, Irvine was an agricultural community with very few students and a small commercial base, and so was spending very little on education.

More changes came in 1976, when the California Supreme Court found that the system of school finance was still inequitable. The state was forced to establish a new set of spending limits, and to ensure that all schools receive roughly the same amount per student, within a $100 range. It narrowed the disparities among rich and poor districts, but didn’t eliminate them by any means.

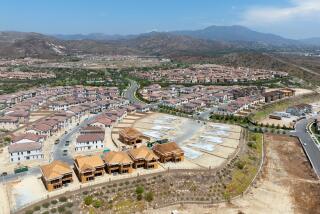

Fast forward to today, and consider what has happened to Irvine.

Home prices--and thus property tax revenues paid by homeowners in the city--have soared along with those in most of the county. But relative to the county’s other unified school districts, Irvine remains rock-bottom in state funding as of the 1998-99 school year, the most recent figures are available.

Over the decades, the state has periodically dedicated additional funds to narrowing the gap, raising the bar on the lowest-funded districts and making cost-of-living adjustments across the board.

But at the same time, because of inflation, the $100 range of funding from the 1970s has grown to a current band of about $332, according to John Gilroy, an official in the fiscal services division of the State Department of Education.

The $332 discrepancy is legal, according to the courts. But James A. Fleming, superintendent of the Capistrano Unified School District, believes otherwise. His district was funded at nearly $44 below the state average last year.

“It’s a completely asinine system that hurts schools in places like Capistrano and Irvine,” Fleming said. “The state of California is engaging in an unconstitutional and illegal allocation.”

Added to the mix was a new funding formula that took effect in the last school year, rewarding districts that raise attendance rates. Schools no longer get paid the allotted amount for each student on days when the students are absent, but they do receive a higher payment for each day a student is actually in class. Districts with relatively high absence rates received a greater increase per student.

Irvine has traditionally maintained consistently good school attendance, with absence rates generally at or below 3%. The district did not lose money in the shift, but other districts that were able to raise attendance rates received significantly more money than before.

“Irvine and other districts are not going to get those bucks because we’re already doing well,” said Crowe.

The new system “didn’t disadvantage anybody,” Gilroy said. “Irvine had less of an opportunity to raise their limits.”

Irvine’s Reed estimates that under the current system, it would take a statewide pool of $200 million to raise Irvine and comparable districts to the state average. The last round of what’s known as equalization funding was $600 million paid to districts between 1996 and 1998.

Gov. Gray Davis’ current budget plan does not call for any additional money to bridge the funding gap, but school officials in low-wealth districts throughout the state are hoping that the state’s strong economy will help their cause. .

And a new $150-million bill, to be introduced by state Sen. Adam Schiff (D-Burbank) late this month, would also seek to narrow the gap.

Lobbyist Bob Blattner, director of legislative services for School Services, will be pressing Irvine’s case in Sacramento. “It looks more and more possible all the time” that cash-strapped districts will see some relief, Blattner said.

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

School Funding

A look at how much was allotted per student by district, for the 1998-99 school year, the most recent figures available.

*--*

Elementary Fountain Valley $4,034 Westminster $4,048 La Habra City $4,064 Huntington Beach City $4,066 Ocean View $4,067 Anaheim $4,070 Centralia $4,071 Savanna $4,071 Fullerton $4,079 Cypress $4,084 Magnolia $4,087 Buena Park $4,093 State Average $4,116 High School Huntington Beach Union $4,878 Anaheim Union $4,905 State Average $4,947 Fullerton Joint Union $4,993 Unified Irvine $4,189 Laguna Beach $4,222 Brea-Olinda $4,223 Garden Grove $4,227 Saddleback Valley $4,228 Santa Ana $4,235 Capistrano $4,236 Tustin $4,242 Orange $4,248 State Average $4,287 Placentia-Yorba Linda $4,381 Newport-Mesa $4,395 Los Alamitos $4,490

*--*

Source: Orange County Department of Education

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.