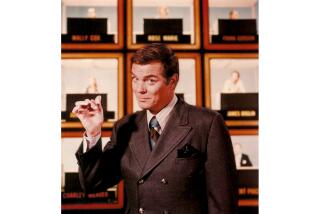

Bill Welsh, TV Pioneer and Local Booster, Dies

- Share via

Bill Welsh, a pioneering KTTV broadcaster and a longtime president of the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce who was often introduced simply as “Mr. Hollywood,” has died. Although Welsh was reluctant to discuss his age, he was believed to be 88.

Welsh died Sunday of an aortic aneurysm in his Thousand Oaks home, Hollywood Chamber of Commerce spokeswoman Ana Martinez-Holler confirmed Monday.

He was considered a founding father of local television and of the $922-million Hollywood redevelopment effort now underway to rescue the crucible of movie-making from decades of decay. The late Times columnist Jack Smith once said of him: “If you saw him walking down Hollywood Boulevard, you’d say, ‘Who is that man? I’ve seen his face a thousand times.’ ”

“Bill Welsh loved Hollywood, and Hollywood never had a greater booster,” said Johnny Grant, with whom Welsh hosted more than 300 Hollywood Walk of Fame ceremonies, placing stars in the sidewalk honoring celebrities.

“He was unflappable and always the consummate professional,” Grant said. “His shoes will be hard to fill.”

Welsh had his own star on the Walk of Fame, placed discreetly about a block west of Vine Street. He had declined a prestigious location near Mann’s Chinese Theater, scoffing: “No. I don’t want 3 to 4 million people coming in from out of town every year and saying, ‘Who’s he?’ ”

President of the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce from 1980 to 1990, Welsh also served on the Project Area Committee for Hollywood redevelopment and was a key force in pushing the renovation plan through the Los Angeles City Council in 1986.

It was Welsh who raised $150,000 in 1983 for a crucial feasibility study, and Welsh who called Mayor Tom Bradley and other community leaders together at a Brown Derby lunch to convince them that redevelopment could--and should--happen.

Initially, the program was highly controversial and opposed by many, who felt massive redevelopment including new hotels, restaurants and high-rise office towers would disenfranchise the poor and minorities. But Welsh never wavered in his campaign to wipe out the grime, prostitution and seediness into which Hollywood Boulevard had sunk and to replace it with glittery and profitable new business and entertainment centers.

“I think it’s an accepted fact that if you’re not moving ahead, you’re falling back, you’re losing ground,” Welsh told The Times in early 1987. “I think redevelopment is going to be so well done that even our loudest critics . . . are going to say, ‘I don’t know why I opposed it. . . . It turned out to be wonderful.’ ”

In a tangential part of his plan, Welsh helped push the Metro Rail Red Line subway through to Hollywood and Vine, serving on the Greater Los Angeles Transportation Coalition and Metro Rail Phase I and Phase II benefit assessment district committees.

Although he made his home an hour away, Welsh considered himself a son of Hollywood as well as a father, and always said the redevelopment plan was his way of giving something back.

“I had a good fortune to get into television in 1946; I grew up with the industry,” he said in 1987. “I’ve had a wonderful life, all because of Hollywood. Now I want to put something back in. When I get older, I want to be able to look out a window and say, ‘You know, we got a better community because a lot of people believed in it, and I was one of the people who believed in it.’ ”

Welsh had bit parts in about 20 movies in the 1950s. He was born in Greeley, Colo., and grew up across the street from Colorado Teachers College. When he enrolled there, he was put in charge of working the public address system at athletic events.

That led to his first job, reading commercials and playing records on local radio station KFKA, where he earned $7 a week but got only about $3 or $4 because the station was too poor to pay the rest. (After he said in a 1985 Times interview that the station still owed him $22, Greeley’s KFKA sent him a check.)

In 1935, when Welsh happened to visit the Greeley police station in search of news, he found it: A police sergeant friend had just been murdered. Welsh’s coverage of the crime was picked up by Denver newspapers, and Denver radio station KFEL offered him a job.

In Denver he covered sports and other events, experimenting with pioneering remote broadcast equipment. He once persuaded Eleanor Roosevelt to wait at the Denver railroad station until he could get the hookup to work.

Welsh got to Hollywood in 1944, lured by broadcasts from Los Angeles radio station KFI of the Phil Harris orchestra playing at the Ambassador Hotel’s Cocoanut Grove. His initial job was with an advertising agency, but Welsh was soon broadcasting USC and UCLA football and basketball games on radio. He made his television debut on KTLA Channel 5 in 1946 announcing a hockey game.

Indefatigable and with unquenchable optimism, Welsh was undaunted by the fact that at the time there were only about 300 TV sets in Southern California.

“I saw television as the future,” he told The Times years later. “People would say, ‘You’re making a terrible mistake. This television thing--it’s never going to happen in our lifetime.’ Three years later, the same people came back and said, ‘Hey, Bill, how do I get into television?’ ”

He was on screen for two seminal events in television history: the first telecast of the Rose Parade and the Rose Bowl game on Jan. 1, 1948, and the live coverage of toddler Kathy Fiscus’ fall into a San Marino well in 1949.

“Stan Chambers [who remains a newscaster at KTLA] and I did 27 1/2 hours live on the air,” Welsh recalled in 1991 when he received the Los Angeles Area Governors Emmy Award. “People had never seen anything like that before in their homes.”

The incident graphically demonstrated the impact of live television coverage and helped expand perception of the new medium from mere entertainment to a revolutionary disseminator of news.

The Kathy Fiscus telecast, Welsh said in another interview, “shut down the town. Nobody went to the theaters. Nobody went to the restaurants. They all stayed home.”

“We put ourselves on the air and just started talking. The equipment kept operating and we were still there when they were able to drill a second shaft beside the well and to find that she was dead. Television was a little more sensitive to people’s feelings in those days. We did not stay on the air to watch them bring up the body.”

But Welsh was asked to do something that no modern newscaster would be expected to do: walk over to the Fiscus house and tell the family their little girl was never coming home.

Welsh signed a permanent contract with KTTV on April 1, 1951, and for years was director of sports and special events. Over his career, he broadcast 49 Rose Parades. He covered 63 sports, ranging from football and basketball to wrestling and jalopy races, lawn bowling, cricket and golf.

The versatile broadcaster also hosted an early version of divorce court, beauty pageants and game shows. He presented a program staged in grocery stores from Santa Catalina to Pomona called “Star Shoppers,” broadcast Hollywood Bowl Easter sunrise services and covered whatever else was going on, including, as Jack Smith once wrote, “cats up a tree.”

Welsh once joked that KTTV kept him on the payroll over the decades because “when they want to do something live . . . they need somebody who can talk and talk and talk.”

The articulate Welsh’s ability to talk without a script served him well on television and in his Hollywood boosterism among citizens groups and politicians.

“The secret of being able to ad-lib,” he once told The Times, “is you’re not really thinking about what you’re saying at the moment. You’re thinking about what you’re going to say next. You’re framing that in your mind and your mouth is on automatic.”

Welsh preferred live television, thought later scripted programming got downright boring, and relished his annual dates in Pasadena for the Rose Parade.

Welsh is survived by his wife, Lucinda Pennington.

Martinez-Holler said a memorial service will be planned.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.