THE THIGH’S THE LIMIT

So far as I know, I was the first in countless generations of my family to wear a bikini. That is, I probably have been more scantily clad in a public place than most--if not all--of my female ancestors since the loincloth era. My photo albums document the diminution of swimwear in the 20th century. I have shots of my grandmother and her sisters at Rehobeth Beach, Del., in the 1920s in saggy, striped knit, knee-length woolen suits said to have weighed two pounds dry and eight pounds wet. The fact that they are not wearing black stockings as well indicates the century’s first major weakening in an ethos of absolute female modesty. At that same beach in the 1930s, I see my mother as a teenager: She is wearing a surprisingly modern-looking, pale-colored one-piece with little briefs that, in turn, are covered by a “modesty panel.” She looks long-legged, curvy and great. My mother married my father in 1946--the same year the bikini was invented by a French designer named Louis Reard, but she did not rush out to buy one. Indeed, bikinis were too scandalous even for the French; professional models there refused to wear them and Reard had to hire a stripper to show the scanty things. Although strikingly full-cut by today’s standards, the first bikini was considered by many people, including my mother, as indistinguishable from a stripper’s G-string. Meanwhile, in the realm of ready-to-wear, American lingerie companies had taken up swimwear design and were employing every structural trick they knew, including built-in bras, stays, bones, zippers and punishing amounts of elastic. Snapshots of my mother as a newlywed on the beach on Catalina Island illustrate the point. She’s wearing a stylish one-piece that’s form-fitted and zippered, with thick straps that tie behind her neck and a puckered, elasticized back. And the bra on that thing! Stay out of its way! In other snapshots from that holiday, my mother sunbathes in a modest halter top and waist-high, zippered matching shorts, a look considered scanty in her time, and as daring and baring a bathing ensemble as she would ever don.

Women’s swimwear has historically existed in the touchy territory between modesty and exhibitionism, flesh and fabric, decency and naughtiness, dress and undress. But it wasn’t until 1952, when the comely but athletic swimmer Esther Williams wore 28 different swimsuits in “Million Dollar Mermaid,” that the bathing beauty became an American icon and the bathing suit became popularly and commercially linked to female sexual desirability and physical ideals. The way a woman looked in a bathing suit was a measure of her perfection--or lack of it.

The one-piece bathing suit became required attire on TV beauty pageants in the ‘50s. In the ‘60s, the naughtier, scantier bikini, popularized by the 1960 song “Itsy Bitsy Teeny Weeny Yellow Polka Dot Bikini,” colonized the poolsides and beaches. But the bikini never earned my mother’s approval. She saw it, correctly, as part of a progressive trend to be as naked as possible in public. Also, the prices scandalized her. So little fabric for so much money.

Ineluctably, the bathing suit continued to shrink, and the gaps between designer swimwear, ready-to-wear and my mother’s idea of appropriateness continued to widen.

Rudi Gernreich made headlines with his topless bathing suit in 1964, right about the time bikinis were de rigueur, and a scant three years later, in 1967, I fought and wrangled and wept and finally forced my disapproving mother to buy me my first two-piece swimsuit. There’s a snapshot of me with two high school friends on spring vacation in Guaymas, Mexico, standing under a cabana, squinting at the camera. My friends wear bikinis that by today’s standards would be considered quite modest--and I’m in a downright matronly blue-and-white checkered suit with inch-thick blue straps and bottoms that look like Carters full-cut briefs (my mother also never condoned bikini underwear). Even so, I loved it. Perhaps it was my first major weight gain of 10 pounds in that first semester of college, or perhaps it was the body-consciousness that comes with maturing, but I would never again take joy in buying and wearing a bathing suit. Once I left home and was free to buy any swimsuit on the rack, shopping became a different kind of torture: a garishly lit, unforgiving study of my body’s imperfections.

Still, in the ‘70s, I wore bikinis because my mother wasn’t there to stop me and I weighed a mere 115 pounds. I managed to embody my mother’s very worst fear (beyond the bikini) and went skinny-dipping and did a lot of topless tanning. Who needed Rudi Gernreich’s pricey product when half a bikini did just fine?

In the early ‘80s, I’m pictured in a pink string-bikini looking pretty darn good. Of course I did. I was compulsively dieting and running seven miles a day. But hey, I was under 110 pounds, and for the first and only time in my life, I managed to have as perfectly constructed a body as obsessive behavior could create.

Once I stopped the regimen, I filled out again, naturally, and reverted to a standard black maillot, very flattering and forgiving. But I was still thigh shy and avoided the camera. In the mid-’80s, a saleslady convinced me to try the new French-cut suit, which was slimming and flattering, especially with regards to the thigh. But it required such torturous waxing that it made grandma’s wet wool suit seem desirable. Around that same time, I was thrilled to see a style called “little boy shorts” in swimwear again, until I tried them on. Although covering far more than any bikini bottom, they proved far crueler, rubberbanding the upper leg so that all but the teeniest thighs and derrieres bulge grotesquely.

And then along came thongs, the suit that stated with absolute finality the rarely acknowledged truth that swimwear can be far more discrediting to a woman’s appearance than complete nudity, especially when it comes to thighs. I steered clear and stuck with the eternal black maillot. There’s me at Zuma Beach in a black Ann Cole with a pretty Kenzo sarong.

The turn of the century in swimwear seems to be about choice and variety. Recently I went swimsuit shopping, and I found myself wistfully, even elegiacally, studying scanty suits as works of art and imagination and loving unconditionally a green beaded bikini by Inca and a Ralph Lauren made from bandanna fabric. The racks of solid electric blue and hot pink and chartreuse Calvin Kleins are just what I spent years searching for. The prints, too, are no longer just a steady diet of fluorescent Hawaiian florals. And the styles are astonishing, from micro-thongs to bathing suits with built-in flotation devices and suits with UV-ray protection and rash guards. There are even bathing suits with sleeves.

Other generously cut suits include “tankinis” and the skinny-strapped “camikinis,” both of which, the saleswoman told me, have the flexibility of a two-piece with the look of a one-piece. She failed to mention how they fit: The tight little top falls an inch short of meeting the tight little bottom, creating a perfect life preserver where my waist used to be.

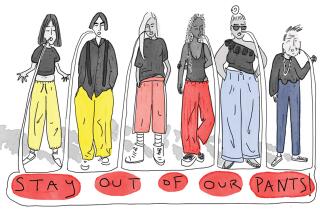

There are smart little swim dresses that minimize every conceivable physical shortcoming, real or imagined. If concealment has finally become as popular as revelation, it’s not due to the feminine modesty that my mother and her mother endorsed. We women conceal because, by and large, we almost all fall physically short of Esther Williams and half a century of Miss Americas and the models in several decades of Sports Illustrated swimsuit issues. We’re thrilled to see cover-ups and “modesty panels” and sarongs and sassy little skirts and the gloriously named hybrid of skirt and short, the “skort.”

Skort. Perhaps in the year 3000 some distant relative will scan her family’s photographic history of swimwear and write with a certain wryness, “And there’s my great-, great-aunt Michelle in a turn-of-the-century skort.”