Rap With Accent Marks

To talk to Jerry Heller these days, you’ve got to get past the rough exterior. Not his. The veteran music executive appears urbane and mild-mannered, more than you’d expect for the man who managed the seminal gangsta rap group N.W.A. It’s Heller’s new business location that seems forbidding.

From the outside of the big slab of a building on Alvarado Street that is headquarters of the fledgling Hit A Lick Records, it looks like nobody’s home. The entrance is protected by a pad-locked iron gate. There’s no sign or doorbell. Trying to knock is futile, because nobody will hear you in the cavernous facility that once housed the IRS, complete with the vaults still in the basement.

But inside, Heller and his two partners, Tony Gonzalez and Pablito Vasquez, have created a high-tech musical incubator for what they hope will be the next big L.A. street craze: homegrown Latino rap and hip-hop.

They’ve remodeled one floor and created a modern complex with high-ceiling recording studios, a screening room with Internet connections under every seat and a private nightclub with a VIP room that has a cigar-smoke extractor and a two-way mirror for discreet views of the dance floor.

“Everything is done right,” says Heller, 60, as he rubs the side of his plush leather chair in the theater which doubles as a conference room. “It has everything we need to be successful.”

Everything, so far, except a big hit.

For its first single, the Hit A Lick team is betting on the smooth and infectious “Dreamin on Chrom,” from an album by G’Fellas titled “Gangster 4 Life.” The tune is sweetened by the R&B-inflected; stylings of guest vocalist Vanessa Marquez, a teenager from Rialto whose parents accompanied her to the recording sessions.

The song’s appealing, party-like video was filmed on the roof of the Hit A Lick building in the tough Pico-Union district, heavily populated by Latinos. The menacing rappers add a charming touch when they come to a line where a profanity should complete a rhyme, but instead put their fingers to their lips and say, “Shhhh.”

“I want my Mom to be able to put on [the song] in the car. My Pops. Everybody, ya know, at the [family] barbecue,” says G-Fellas’ Nino Brown, whose real name is Gilbert Ruedaflores from Hacienda Heights.

Though other cuts are far from G-rated, Heller calls this one “radio friendly,” a good summer song for cruising the boulevard. The album made an appearance at No. 68 with a bullet on Billboard’s R&B; chart this week. Not a smash, but enough to boost the morale of the struggling company.

“We’re thrilled,” says Heller, affectionately called Pops by his crew. “It’s very difficult to come in cold turkey and sell a movement, but this [success] will draw national attention and set the stage for the records we have coming.”

Hit A Lick is the only Latino rap label with a stable of signed artists, he said. They include two pioneer Latino rappers--Frost, formerly known as Kid Frost from the 1990 hit “La Raza,” and Mellow Man Ace who had the bilingual hit “Mentirosa” the same year.

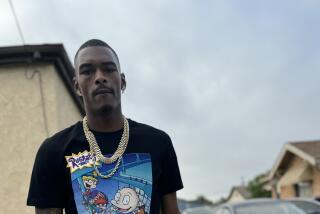

Rounding out the roster are a 20-year-old rapper-composer who goes by Lil’ Blacky, and gangsta rap groups Eastside Ghetto and Big Shots With Malice and ALT. And don’t forget MWA, a Mexican takeoff on Heller’s notorious Compton group.

“Maybe we don’t have the exposure yet,” says Heller, “but we don’t have the competition either.”

The Hit A Lick concept originally came from Pablito, the label’s streetwise president who was so good at building low-rider cars he exported Impalas to Japan. He hooked up with producer Gonzalez, a former deejay and music mixer (known as Tony G.) who worked with Heller at Ruthless Records, which launched N.W.A. Pablito, a Mexican American, and Gonzalez, a Cuban American, designed and remodeled the current Hit A Lick facility and invited the semiretired Heller to come on board in the spring of 2000.

“I’m going to go for it,” Heller recalls saying after seeing the setup. “I think I can do this one more time.” Heller had backed away from the music business after his tumultuous relationship with N.W.A, which detonated the explosive gangsta rap movement with the groundbreaking 1989 album, “Straight Outta Compton.”

The band--hailed by critics but condemned by others for its violent lyrics and anti-authority messages--broke up in a hemorrhage of bad blood. After leaving N.W.A in a dispute over money, Ice Cube lashed out at the group and its manager Heller in the 1991 rap song, “No Vaseline.”

Heller was also involved in a bitter legal battle with the estate of Ruthless’ co-founder Eric Wright, alias Eazy-E, who died of AIDS in 1995 at 31. That suit was settled in December of 1999.

Heller is still entangled in another legal dispute over what he considers his false and misleading portrayal in “Have Gun Will Travel,” a book about Death Row Records written by Ronin Ro and published in 1998 by Doubleday. A trial court threw out claims of defamation and invasion of privacy made by Heller and two other plaintiffs. That ruling was partly reversed earlier this year in reference to one allegedly false statement made against Heller. A new trial date has been set for Dec. 12, Heller said.

“Maybe it was a hiatus,” says Heller of his retreat from the industry. “Maybe I was burned out. But retirement is so final. In my mind, I don’t think I was ever out of the music business for good.”

Despite past controversies, Heller’s new partners express faith. “I know what kind of gentleman this is,” Gonzalez says. “I’ve worked with Jerry since 1985, and all we ever had was one handshake.”

A former agent who represented such varied talents as Johnny Mathis and Van Morrison, Heller remembers the exact date when he and Eazy-E founded Ruthless Records: March 3, 1987.

“People laughed at me,” he recalls. “They thought it was the craziest thing they had ever heard.... But it was absolutely the most important period of my career, because I feel that gangsta rap was the most important movement since the beginning or rock ‘n roll. . .

“N.W.A (artists) were the first great rap audio documentarians of the problems in our inner cities. The fact that we had this new art form called rap, gave them the stage to present these problems to white, middle-class America.”

Heller said he structured Hit A Lick just like Ruthless, giving artists, for example, complete creative license and 24-hour access to the studios.

Whether he can duplicate that success at Hit A Lick remains a big question. The demand for Latino rap is not exactly a groundswell yet.

Gonzalez is aware of the challenges. But he notes that he produced the hits for Mellow Man and Frost more than 10 years ago, “when people still were saying the country wouldn’t listen to Latinos on radio.”

Frost believes he was ahead of his time. But he’s none too pleased with the current state of Latino rap, which got “stuck in cliches about things we don’t have.... Chicano rappers are talking about hitting switches in low-riders, then you see the dude and he’s in a broken-down Hyundai.”

Frost, whose real name is Arturo Molina, is now a father of three and lives in Pasadena. His 13-year-old son is also an aspiring rapper who calls himself Scoop DeVille, just a kid in diapers when his heavily tattooed dad had his hit.

“It’s time to start new, with the young Latin age group,” says the teenager, lounging at Hit A Lick one recent afternoon with his father and fellow rappers.

Heller is ready too.

“I was just waiting for something where I could tell my friends I did it again,” he says.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.