Bonannos Self-Destruct as Stand-Up Guys Fade

NEW YORK — They appeared in the courtroom barely 30 feet apart, the notorious past and noxious present of the Bonanno crime family.

At the defense table sat a stand-up guy: Anthony Spero, reputed Bonanno consigliere, placidly sucking a fruit-flavored Life Saver. His face betrayed no emotion during his racketeering trial last March. Spero, 72, wore a dark, conservative suit and tie.

During a lifetime in the Mafia, Spero kept his mouth shut, even while serving a two-year extortion rap. He remained a figure of mob respect, a man who had dined with the late boss Carmine Galante and attended the wedding of John Gotti’s daughter.

On the witness stand sat a self-professed “rat”: Joseph Calco, a Bonanno hanger-on. Calco, 33, ran with street thugs like “Eddie the Crackhead.” He picked up tips on mob life from television and magazines.

Facing a life sentence for murder, arson and drug trafficking, he turned federal informant.

Growing up in Brooklyn, Calco had revered Anthony Spero; his best friend was Spero’s godson. And now Calco’s testimony, in this antiseptic courtroom, could jail Spero for life.

After the Brasco fiasco of the early 1980s, the Bonannos had tried to avoid both headlines and prosecutors.

But boss Philip “Rusty” Rastelli and his underboss were convicted of racketeering in 1986, and 18 Bonanno-linked Mafiosi were jailed a year later for running the “Pizza Connection”--an international heroin ring that moved its product through pizzerias.

The family was increasingly in the shaky hands of made men like Tommy Pitera.

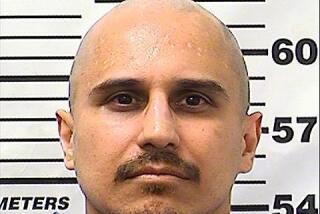

Short and steely eyed, with a once-broken nose and slicked-back hair, Pitera personified the new-breed Bonannos.

If Joe Bonanno was considered a man of honor among the mob, Pitera was undeniably a man of horrors. His home library included “The Hitman’s Handbook” and “Kill or Be Killed.”

“Tommy Karate” practiced what he read. He was charged in 1992 with nine murders, and blamed for two dozen more. He was the poster boy for the new Bonannos: drug dealer, psychotic killer, obvious law enforcement target.

Typical Thugs Meet Typical End

Pitera’s bunch was a typical ‘80s Bonanno crew. His 30-man gang butchered drug dealers, then stole and sold their heroin, cocaine and marijuana. The dismembered victims were buried in a Staten Island bird sanctuary.

His demise was typical too. In 1992, helped by the testimony of a dozen mob turncoats, Pitera was jailed for life.

By then, Anthony Spero was the acting Bonanno boss after Rastelli’s death in jail. Spero, then 63, aspired to a Joe Bonanno-style retirement, tending to his homing pigeons on a Brooklyn rooftop.

“I’m getting old,” he had told a federal investigator shortly after his promotion. “You won’t see me around here.”

But Spero continued operating from his private social club in Brooklyn’s Bensonhurst section.

While a boss like Joe Bonanno was far removed from the streets, Spero enjoyed little insulation.

By 1994, federal authorities estimated the Bonannos numbered between 50 and 75, a fraction of their former manpower. Now the weakest of the five families, the Bonannos watched their revenue dry up as Vincent “The Chin” Gigante and the Genovese family established themselves as No. 1.

The Rastelli conviction shut down money from the city’s moving and storage business, while a 1992 prosecution booted the mob from the garment district. In 1995, Mayor Rudolph Giuliani ejected six allegedly mob-affiliated companies from the Fulton Fish Market.

While Giuliani took on the fish market, Joe Bonanno celebrated his 90th birthday at an Arizona gala attended by “Godfather” actor Alex Rocco and author Gay Talese.

In Brooklyn, Spero had finished his stint as acting boss. His brief reign would later come back to bite him.

In the late ‘90s, Spero was targeted by federal authorities through his ties to “The Bath Avenue Crew.” The Bensonhurst street gang was slow-witted and quick-tempered. They earned money through burglaries and dope deals, not multimillion-dollar concrete payoffs.

The Bath Avenue boys included seven gunmen, each with a number--1 through 7--tattooed on his ankle.

The group’s leader was Paul Gulino, a Tommy Karate protege desperate to become a made man. When that didn’t happen fast enough, Gulino announced plans to kill Anthony Spero.

Spero was not amused.

An angry Spero sent out the word: “Paulie’s got to go.” One Sunday morning in 1993, crew member Joseph Calco put two bullets in Gulino’s head. A short time later, the ninth-grade dropout was greeted on the street by Spero with a kiss and a hug.

“You’re a good guy,” Spero reportedly told Calco. Spero allegedly ordered two other murders: one of a Bonanno wannabe who had botched a hit, another of a burglar who had robbed his daughter’s home.

Spero was indicted for the slayings in May 1999. Last year, Calco became a federal informant to dodge his own life sentence for murder and assorted crimes.

Calco’s testimony against Spero was incriminating, if not always intelligible. The key prosecution witness spoke about standing in the “foley” of a mob social club.

“Like a foyer?” a federal prosecutor inquired.

“Foy, foyer, whatever, however you say that,” replied Calco.

The jury heard from Calco and nine other informants, then took just two days to convict Spero. The septuagenarian mobster, convicted in April, appears destined to die in federal custody.

Few Family Crews Remain Active

The Bonannos’ future is not bright. They claim just eight working crews--street gangs like the Calco bunch, not the well-oiled operators of the past.

Its one positive--continuity of leadership--only makes reputed current boss Joe Massino an enticing law enforcement target. One prosecutor estimates the Bonanno operation could be finished “in two to five years.”

Whenever that happens, the family’s cause of death will be suicide.

Nearly two decades ago, Joe Bonanno griped that people like Pitera and his ilk were not worthy of carrying his surname. Two years ago, his son Bill expressed the same emotions.

“There has not been a Bonanno family since 1968,” Bill Bonanno said bluntly. “The people in my world fell into the same trap as society in general. They’re a product of ‘the opera generation--me, me, me.’

“It is a different mob.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.