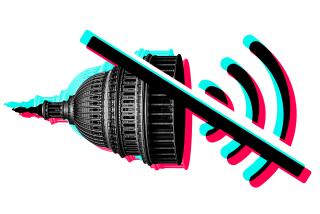

Are Music Videos at Risk of Becoming Same Old Song?

For the record, they’re known as music videos, not “music Viacoms.” But given that Viacom now owns MTV, MTV2, VH1, VH1 Classic, Country Music Television and, soon, Black Entertainment Television, the broadcasting behemoth can pretty much call them anything it wants.

For the viewing public, some observers say, the consequences roughly parallel what’s going on in music radio: As big corporations (including Viacom) gobble up FM stations, playlists have taken on a strip-mall sterility, often heavy on mass-marketed fluff.

“It’s like a conspiracy theory, you know?” countered Viacom spokeswoman Susan Duffy. “Our networks try to put the best possible entertainment on the air, and that’s what their goal is. . . . I don’t think we’ve even been accused of favoring a particular label--and MTV’s been in business for 20 years.”

Still, Viacom’s $3-billion deal a couple of months ago to acquire BET means that it’s likely to serve as the undisputed gatekeeper for music video airplay. And while Viacom has promised to leave creative control in the hands of its respective channels, there’s no telling how long that promise will stick--and how tight a grip Viacom might choose to exert on everyone from record industry executives to the owners of competing music video outlets.

“If you’re an artist or a record company that has poor relations with the Viacom culture, you’re immediately stripped of most opportunities to get your music videos on the air,” said Stan Soocher, an attorney who is chairman of the entertainment industry studies department at the University of Colorado at Denver. “Clearly, it’s beneficial to have more ‘stores’ to sell to in the music video mall, so to speak.”

Soocher added that from a legal standpoint, there could even be possible antitrust concerns, though he noted that “almost all of the Viacom channels offer different forms of programming, and almost all artists fit onto one or two types of channels rather than all of them. So at least you’re facing a situation where not all of the Viacom channels are broadcasting one type of music. If that were the case, the industry would be in a crisis mode from a music video standpoint.”

Viacom’s Duffy emphasized this programming diversity. “They’re going to pick their own videos, they’ll buy their own videos, and they’ll continue to determine their own programming,” she said. “They’re going to continue to do what they’ve always done, which is make their own creative decisions. There isn’t one grand pooh-bah of music video programming here.”

Further complicating the issue are the simple mechanics of music videos. “Most acts don’t make videos now because there is no place to take them,” said Alan Light, editor in chief of Spin magazine. “You’ve got to spend a lot of money on a video to have some chance of it getting shown, and it’s got to be a franchise act. It’s a hard thing to break through.”

Part of the problem is that, under Viacom, music channels have shifted away from videos and more toward lifestyle programming, such as MTV’s “The Real World.”

“You can’t really track ratings on music videos because people watch with one hand on the remote,” Light said. “You talk to people at those channels and they say, ‘We tried shows with just music videos and we just don’t get the numbers.’ ”

Viacom’s line on the BET purchase is that the network will remain much as it was, headquartered in Washington with founder Robert L. Johnson staying on as chairman and chief executive.

“They’ll have access to greater financial resources; they’ll leverage our marketing,” Duffy said. “We have 24 radio stations that are really urban, so there could be synergies between them. I think it’s only going to be a positive for the BET brand and the record labels that promote their music on BET.”

At least one competitor isn’t afraid to say that it feels like a David facing down a broadcast Goliath.

“If you just look at the rest of the satellite and cable television landscape, every other genre has multiple providers and is a competitive landscape--news, women, sports, movies,” said Nora Ryan, general manager of MuchMusic USA, a New York-based music network. “In the end, that’s more choices for the consumer, more editorial points of view and a broader portfolio for the cable and satellite providers. But in music, if any channel other than Viacom makes it, Viacom buys them.”

MuchMusic USA has ambitious plans to more than double its distribution in the months ahead, and gain loyal viewers by doing what Viacom’s channels are seen as no longer doing--giving considerable exposure to new and unknown artists, along with established pop acts such as Hanson.

“Our playlist and video rotations have a focus beyond the video Top 40,” Ryan said. “There’s much more breadth in terms of different types of music, and we have a pointed focus on breaking new artists. . . . That, to us, has been a major point of contention between us and MTV.”

Then again, one has to wonder whether such a strategy will doom the channel to ratings oblivion; will viewers give relatively unknown bands a chance? Ryan thinks so and believes that her channel has pinpointed what might be Viacom’s Achilles’ heel: In the name of ratings and demographic dominance, she said, it no longer takes creative chances.

“If you are so big and so rooted in a brand, after a while the brand comes to define and limit what you’re going to be,” Ryan said. “Therein lies the opportunity for us to come in and fill the gap.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.