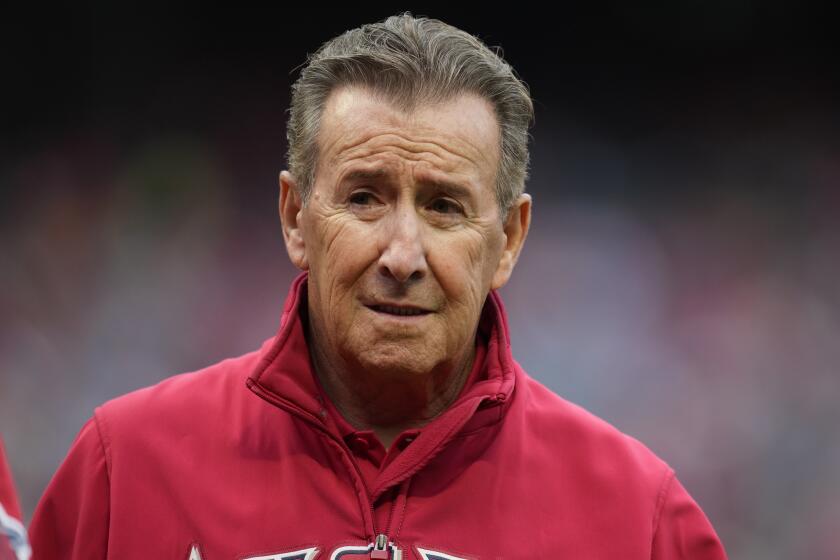

Fame Came Suddenly, and Name Never Left

I first met Bo Belinsky by the pool of the old Desert Inn in Palm Springs.

It was the spring of 1962. Belinsky was a 25-year-old southpaw the then-Los Angeles Angels had selected from the Baltimore Orioles in the minor league draft the previous December.

He had yet to throw a pitch in the major leagues, but he already had a reputation as a cocky, pool-playing wise guy from New Jersey, a kid who had dazzled scouts in the Oriole minor league system but whose discipline didn’t always match his talent. He had reacted to the opportunity the second-year Angels were presenting by staging a contract holdout--”I can make $6,500 shooting pool,” he said of the club’s offer while demanding $2,000 more--and arriving late at his first big league training camp.

Imagine. With his young club hungering for a charismatic personality, with eager Angel reporters having already unearthed some of the wild anecdotes from his untamed years in the Oriole system and salivating at the thought of hearing from the real thing, there he was finally sitting by the Desert Inn pool, wearing shades to deflect the sun, a drink in his hand, perfectly at ease in the sparkling environment, as if he was already the toast of the town and this was just one more introductory news conference.

Emerging from that surreal setting, little could we anticipate the extent to which Belinsky would become the toast of the town, indeed.

Little could we anticipate how his, the club’s and our own lives would change as we tried to keep pace with his dizzying odyssey under the neon lights of the Sunset Strip and his escapades on and off the field.

Little could we anticipate that he would begin his rookie season with a 5-0 record, including a no-hitter against his former Orioles, or that he would soon be dating Mamie Van Doren, Juliet Prowse, Tina Louise, Connie Stevens and Ann-Margret, among other Hollywood actresses, or that Walter Winchell would be flying out to report on his activities as he toured the Strip in a candy-apple-red Cadillac.

Nor, of course, could we anticipate then how quickly it all would end, how the early promise would dissolve in all the late nights, how the Angels would fine him, send him to the minors, ultimately trade him, and he would end up pitching for five big league teams, winning only 23 games after that 5-0 start, losing 51, and how, when we wrote about him in succeeding years, as we often did, it would be in the context of how the magic turned to illusion, of how the neons faded but the memories of that far different time and a far different era remained vivid.

As Belinsky himself often said, “I’ve gotten more mileage out of winning 28 games than most guys do winning 200.”

Now we write in the context of an obituary. Belinsky died Friday in Las Vegas, his home for the last dozen years.

He would have been 65 on Dec.7, but bladder cancer, heart disease and hip replacement took a toll in recent years.

He died peacefully on the couch, his television on, a long way from the bright lights and champagne of his no-hitter, but regrets? A wasted life and talent? Should that be the context?

Maybe it’s more important to know that Belinsky salvaged many of his final years, that he came back from the degradation of a derelict’s existence to throw away the brown bag and deal with his alcohol and drug abuse, that he found God in his later years, became active in the Trinity Life Church, was productive in promotional work for the Findlay Management Group in Las Vegas and made several unsuccessful attempts to reunite with his three daughters from failed marriages to former Playboy centerfold Jo Collins and Janie Weyerhaeuser, heiress to the Weyerhaeuser paper and building materials conglomerate.

On Thanksgiving night, Belinsky had visited a good friend, Louis Rodophele, and his family before returning to his house.

“The real Bo is not the guy everyone envisions 35 years ago,” an emotional Rodophele said Saturday. “Bo had accepted his situation. He was at peace.”

Rich Abajian, another friend and the general manager of the car dealership where Belinsky worked, concurred.

“Bo’s life in recent years may not have been as exciting as it once was, but it was a lot more fulfilling,” said Abajian, a former football coach at Nevada Las Vegas.

“He found Christ, he was active in the church, he read the Bible, he was content. Bo would say to me, ‘Rich, if I had led my life the way I’m leading it now, I’d have won a Cy Young Award.’ And I’d say, ‘Bo, that may be true, but we all take different paths and we can’t look back.’

“I mean, for a long time everything was about Bo and the moment, but he became a lot less selfish and a lot less needy. ... I’m not sure I would describe him as happy, but he was definitely at peace.”

He was also headed back to Dodger Stadium in a couple of weeks, where a production company headed by Maury Povich was to begin work on his life story. Might he have won a Cy Young Award? Well, many in the business, including then-Angel manager Bill Rigney, described him in their moments of frustration as a guy with a million-dollar arm and a two-bit head. Tuning up for his no-hitter, Belinsky acknowledged spending the night before with a woman he had met in a Sunset Strip bar.

“I went back to find her the next night and couldn’t,” a glib Belinsky would say. “That’s when my luck began to turn.”

There was more to it, of course, and Belinsky knew it, knew as he told me not long ago that the bills would eventually come due and he wouldn’t be able to cover them. A fight with sportswriter Braven Dyer in a Washington hotel room served to end his career with the Angels, accelerating the spiral.

Belinsky looked back from a different perspective recently and said, “We all tend to spend the first 40 or 50 years of our life satisfying our egos, the next 10 or 20 trying to wipe the slate clean. I’m at that second stage.”

Who’s to judge whether he cleaned the slate completely?

Dean Chance, the former Angel pitcher who did capture a Cy Young Award despite being a running mate of Belinsky’s during those halcyon days and is now president of the International Boxing Assn., reflected from his Ohio home Saturday and said, “Bo did it his way and I don’t think ever had any regrets. We made mistakes, tried not to hurt anyone. We were kids in a different time, pitching in a great city.

“It was like feeling you had the world at your feet, like it would never end, and I think about those good times a lot and often talked to Bo about them. I can also tell you that if I had a dollar for every time somebody asked me where Bo was and what he was doing, I’d be a wealthy man. Everybody remembered him, and I’m just glad he got his life straightened out and knew in his last years where he was going.”

Chance referred to heaven. Many might have thought Belinsky was one Angel who would never get there.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.