Death Awakens Soccer World

LONDON — Jeff Astle was known in the 1960s English soccer world as a player who was “good in the air,” a forward whose ability to out-jump defenders and head the ball into the net made him one of the great goal scorers of his era. Former teammates at West Bromwich Albion in Birmingham remember him as a brave, powerful athlete, and long after he’d retired, fans still hailed him on the city’s streets as “the King.”

Yet when he died last January at 59, after a four-year illness, Astle couldn’t remember anything about the game he loved, or even the names of his grandchildren.

Last month, a coroner ruled it was heading the soccer ball that had killed him.

“There was evidence of soft trauma to the brain from continual heading of a heavy football,” said South Staffordshire coroner Andrew Haigh, who’d ordered the inquiry into Astle’s death.

All those balls bounced off his forehead and toward the net or the feet of teammates were, it turns out, like taking jabs in the head to a boxer.

The coroner’s ruling was registered as “death by industrial disease,” but the implications for the sport in Britain are potentially more dramatic.

It marks the first time any legal ruling has linked heading a soccer ball and degenerative brain disease. No one knows how many soccer old-timers are living out their years in the fog of damaged brains but the anecdotal evidence suggests Astle was not a rare case, and professional soccer is only now realizing it may have a big problem.

“Oh there are quite a number of footballers who died of it,” said Tom Finney, 80, one of the legends of English football.

Finney ticks off the names of some who ended their days suffering from Alzheimer’s-like symptoms. And he repeats the conventional wisdom that the old, heavy leather balls the game once used are to blame.

“Now Willie Cunningham, if he headed that ball, he used to pass out,” Finney said.

The sport’s establishment accepts the heavy-ball theory, noting that current synthetic balls are lighter and -- crucially -- engineered to be water repellent. Astle was part of a generation that played with a ball that took on water as it rolled along wet grass. The sodden ball would as much as double its one-pound weight by late in a game.

Those who played with the old leather recall it with dread.

“On a wet day, just kicking it was bad enough,” said Willie O’Neill, who played with Glasgow Celtic in the mid-1960s.

O’Neill just laughed when asked if he’d been a big header of the ball.

“The name of the game is football,” he said.

Recalled Barry Fry, 58, a teammate and friend of Astle, “You had loads of concussions in those days, but we just gone on with it, really. Those old [fields] didn’t drain well and sometimes we’d play through six inches of mud and muck. That laced ball would cut your forehead, cut your eye if you caught it wrong.”

Since the ruling on Astle’s death, there have been numerous attempts to describe what it felt like to head a leather ball. A bag of bricks is the most popular analogy. A half-ton of impact, offered one ballistics expert.

“Think of someone heaving a bag of potatoes toward you, then you rise to meet it while twisting your neck to redirect it,” said professor David Graham of the Institute of Neurological Sciences in Glasgow, one of Britain’s leading authorities on brain injuries. “Because you have one or both feet off the ground, you’re not stable, so it may cause the brain to move inside the head.

“It’s the movement of the brain against the skull that causes the damage,” Graham said. “Even if you meet the ball head on, the brain will still move.”

Before thousands of soccer moms and dads dissolve in panic, Graham points out that he isn’t drawing any firm conclusion on whether heading the ball leads to cognitive impairment in later life.

“You’d have to test for other factors, such as whether the lifestyle of the post-career athlete enhances their predisposition to changes in the brain,” he said, a diplomatic reference to the hard-living ways of English soccer.

The style of play also has changed, with the ball played much more along the ground than in the air these days. In retirement, Astle would watch games on television and complain that players would not go up for the ball.

“Jeff would go, ‘Ah, they’re frightened of messing their hair up now, they don’t want to move the gel along,’ ” said his widow, Laraine Astle.

But with compensation lawyers warming up their briefs on the sidelines, the game’s authorities are taking a harder look at the health implications of heading the ball.

England’s Football Assn., while expressing sorrow but no culpability for what happened to Astle, commissioned a study last year into the effects of heading. Thirty young players identified as having good prospects for long careers are participating in tests that will measure any changes to their brains over the next 10 years.

But some science on the subject already exists. Norwegian researchers first detected a problem in 1989, when a study of 33 members of their national squad found one-third suffering from “central cerebral atrophy.” A wider Norwegian survey three years later discovered 80% of an even bigger sample of active and retired players showed at least mild neuropsychological impairment, described as headaches, dizziness and irritability.

They also had a “significantly higher incidence and degree” of spinal damage than the rest of the population.

“So what?” goes one school of thought. All high-performance athletes are pushing their bodies to extremes and doing damage in the process. How does heading a soccer ball stack up against the health risks of, say, the use of steroids or the helmet-to-helmet impact in American football?

After all, according to one report, more people are killed in soccer by poorly anchored goalposts falling on them than from heading the ball. And kids are now playing with a smaller, lighter ball, making it a safer game -- even if the American Youth Soccer Organization did narrowly reject a proposed rule change last year that would have banned heading for players under 10.

Yet with manufacturers bragging that their labs produce a modern soccer ball that can be kicked at up to 114 mph, perhaps players are entitled to full disclosure before they decide to stick their brain in front of it.

“Jeff never thought about it, it was his job,” Laraine Astle said.

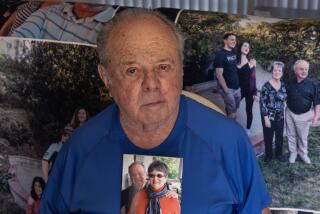

She met her future husband when they were teenagers and they were married for 38 years. She wept as she told how, over four years of wasting health, he turned from a “happy-go-lucky man with a marvelous memory” into a restless invalid, angry and unaware what was wrong with him.

“More than half his goals were scored with his head because he knew how to do it properly; he always hit it in the right place,” she said proudly. “He was the best header in the game. And now he’s gone and can’t see his grandchildren, because football killed him.”

The coroner’s verdict has given her something to hang onto.

“There are people in the game who would like this swept under the rug but they can’t pretend anymore,” she said. “I won’t let it go away. I want to know what football is going to do about it.”