The cultural flowering of Germany’s Jews

The number of Jews living in Germany was tiny, never more than 1% of the nation’s population and less toward the end, with the advent of Hitler. But their share in the cultural, social and economic life was far in excess, and their prominence might have been a reason for their undoing. Their contribution to science, the humanities, literature and the theater was enormous; in the plastic arts and music, they acted as catalysts, as leading sponsors and agents of new forms and contents. Even an anti-Semite like Wagner owed much of his triumph to his Jewish admirers.

This great role of a small minority is all the more remarkable as the exodus of the German Jews from the medieval ghetto came only late in the day. In 1743, a 14-year-old boy from the provinces walked 100 miles of hilly countryside to arrive in Berlin (as yet closed to all but a handful of privileged Jews) to serve as tutor to the children of one of these families. Moses Mendelssohn (the grandfather of the composer) would later become the interlocutor of some of the leading cultural figures of the day, and, more important, the pioneer of Jewish emancipation -- or, as latter-day critics would say, of assimilation.

It took another hundred years for German Jews to get de jure equality, longer for de facto acceptance. From the early 1800s up to 1918, it was virtually impossible for a Jew to serve as a government official, let alone as a reserve army officer (a crucial status symbol in Imperial Germany) even though they were required to serve in the army. The German-Jewish symbiosis, in other words, lasted for less than a century. But it is also true, as Amos Elon notes in his new book, “The Pity of It All: A History of Jews in Germany, 1743-1933,” that Germany was by no means the most anti-Semitic country in Europe, as some historians have argued.

On the contrary, the overwhelming majority of Jews in Germany were patriots and optimistic. During the century before World War I, German Jewry lost most of its upper class; many, especially among the wealthy and the educated, converted to Christianity either out of a genuine conviction to do so, or else because they could not get, for instance, a professorship or a judgeship as a Jew. The percentage of mixed marriages was so high that some concerned demographers predicted the virtual disappearance of German Jewry within three, or at most, four generations.

In later years, the very concept of a German-Jewish symbiosis came under bitter attack by, among others, Gershom Scholem, the great German-Jewish scholar of mysticism. As Scholem saw it, this love affair had been strictly one-sided, a chase after a chimera: The desire of many young Jews to be accepted by German society at almost any price was aesthetically displeasing, devoid of dignity and accompanied on occasion by self-hate. But it should be recalled that Jewish heritage -- after so many generations of stifling ghetto life -- was hard-pressed to compete with the attraction of Goethe, Beethoven, the Romantics and European culture in general. All that remained was a heavy emphasis on meaningless rituals; having been born Jewish was for many nothing but a stigma, and it came as no surprise that after three generations, not a single of Mendelssohn’s many descendants was still Jewish. In the often-quoted words of Heinrich Heine, baptism seemed the entry ticket to European civilization.

Elon shows greater empathy for the converts and the non-Jewish Jews than for those who tried hard to find some positive content in Judaism. Martin Buber is called narcissistically obsessive, Felix Theilhaber hysterical, and historian Heinrich Graetz appears a narrow-minded simpleton. For the historian of ideas, the non-Jewish Jews are far more interesting.

Elon describes the rise of anti-Semitism both on the ideological and popular level during the 19th century. But with all this, German Jews were doing well; if the grandfathers had been hawking goods in the countryside, the sons had a shop and the grandson quite often went into a profession, usually medicine or the law. Frequently, Jews became booksellers, and selling books was the stepping stone to publishing. By the end of the century, they were in the forefront of German cultural life.

What caused such a burst of creativity? A variety of reasons have been adduced: the stimulus of suffering, tribal pressure, the interplay between challenge and response. For all one knows it might have been a mixture of all these and a number of other factors. But in the final analysis, we do not know, just as one cannot account for the flowering of painting in the Netherlands in the 17th century or of music in Austria at the end of the 18th century or German classicism and romanticism in literature.

They welcomed like all others the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 and even more so World War I in 1914. Elon exaggerates a bit describing as unique the support of German (and Jewish) intellectuals for their government’s bellicose policy. It was indeed not a page of glory in the history of the German intelligentsia, and unique it was not. French martial enthusiasm in 1914 was equal, and philosopher Henri Bergson (whom Elon quotes as an example for a more detached attitude) was anything but an opponent of the war.

In this book, Elon goes over ground that is not exactly virgin soil. Although there still are some major lacunas, an enormous literature has been created since World War II on German Jewry. Few groups of people in the annals of mankind have been as thoroughly studied as Germany’s Jews. But it is also true that most of this literature has not been written for a wider public. This book has much to recommend itself: The author did his homework, he immersed himself in the existing literature, he writes well, he is a master of the telling anecdote, and his judgment cannot often be faulted.

It is less certain, however, whether it can be considered a history of the Jews in Germany. For instance, Elon says there is little religious content in the work of Albert Einstein, Sigmund Freud, Gustav Mahler, Stefan Zweig, Franz Werfel, Edmund Husserl, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Paul Ehrlich, Richard Willstatter, Fritz Mauthner or Franz Kafka. This is a perfectly correct statement, but there is something curious with this list (and similar ones in this book); of the 11 luminaries he mentions, most were not German citizens, and six were not Jews. They had either converted or otherwise had formally dissociated themselves from the Jewish community.

We live in an age in which the term “Jew” and “Jewish” is used even more broadly than by the authors of the Nazi Nuremberg Laws in 1935. Obviously, a book titled “Hitler’s Jewish Soldiers” will attract more attention that one called “Hitler’s Quarter-Jewish Soldiers.” But this custom should be resisted. A great many of those appearing in this book belong to wholly different traditions -- namely Vienna and Prague. German was their native language, but they were not part of German Jewry.

There is another, even more weighty, reason. “The Pity of It All” deals essentially with the great figures of that period, the wealthy and the famous. But the great majority of German Jews were neither Nobel Prize winners nor multimillionaires, but middle-class merchants or lower-middle-class artisans or even working-class people. Not very interesting people perhaps, but they were German Jewry, not Hugo von Hofmannsthal. Could a history of French Jewry be written focusing mainly on Jacques Offenbach, Pissarro, Proust and Leon Blum? Or one on Jews in Britain that concentrated on Disraeli, Viscount Samuel and Siegfried Sassoon?

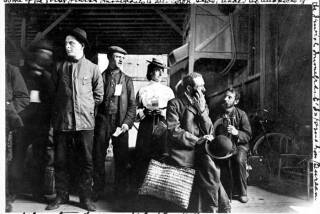

Elon could argue that the situation in Germany was different because the cultural contribution of the Jews was so much greater. True, but the overwhelming majority still did not belong to the intellectual elite. There was a significant number of religious orthodox among them, as well as of Ostjuden, those recently arrived from the East. Readers of a history of Jews in Germany would like to know about how they lived and where they lived and what they did, about their manifold organizations, their schools, their religious leaders, their publications and so on -- not very inspiring stuff perhaps, but essential in a history of this kind.

In brief, one should be grateful for what Elon has done, but the history of an intellectual elite is not a history of a far broader community. Perhaps he can be prevailed upon to change the subtitle in future editions.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.