Drug Ballads Hit Sour Notes

TIJUANA — It was supposed to be the day the music died.

In an elegant hotel salon, the governor of Baja California gathered with guests of honor to witness a solemn promise to purge the state’s radio airwaves of “narco-ballads”--songs about narcotics traffickers--a genre as popular, gory, and hard to banish as gangsta rap.

“Narco-ballads set a bad example for the younger generation,” said Mario Enrique Mayans Concha, the sober, suited president of the Baja California chapter of Mexico’s Chamber of Radio and Television Industry, who has presided over the 2-month-old ban.

But on a recent night at a crowded Avenida Revolucion hangout, men in 10-gallon hats, leather dusters and cowboy boots were stamping their feet and singing along to a narcocorrido about a death match between a drug lord and a cop.

This is Mexico’s latest culture war, unfolding on its newest front: the cradle of the Tijuana drug cartel.

For the establishment, the enemy is narcocultura, the pop culture fascination with Mexico’s gangster underworld and its overlords.

Officials are tired of seeing reliquaries of the so-called narco-saint, Jesus Malverde, sold on the steps of the downtown cathedral. They’re tired of seeing the accused Tijuana drug lord Eduardo Arellano, as photogenic with his tousled good looks as a jeans model, smiling jauntily back at them from a “Most Wanted” poster at the U.S. border crossing.

They’re irritated that a growing number of young people seem to know by heart the lyrics of a tune that boasts that “the little Colombian rock is making me famous.”

But can Mexico, a U.S.-certified partner in the war on drugs, quell a popular regional musical genre with an official scolding? When senior clergymen called for a government ban this summer on a Mexican movie about a carnally passionate priest, the film became a runaway hit.

Mexican regional music, which includes narcocorridos, already claims slightly more than half of the $600 million a year in U.S. sales of Latin music--and Los Angeles is a major market.

“Ballads are a tradition in Mexican music, it’s true--but ballads about the heroics of the Mexican Revolution, and other historic moments,” said Mayans, of the radio trade association. “The narco-ballad is not a tradition.”

But narcocorridos are a modern manifestation of a musical tradition that is as old as Mexico itself. Around the campfires of the Mexican Revolution, troubadours rallied illiterate soldiers and peasants with songs about battlefield victories. During Prohibition, they sang of rum-runners. In modern times, they celebrated heroes like Cesar Chavez.

Today they sing of drug lords, with such faithful attention to headlines that one Tijuana television journalist used a narco-ballad as the mock narration for news footage of a splashy murder.

It was a particularly grisly drug killing that provided the catalyst for the movement to ban the ballads, some say.

In February 2001, masked men with automatic weapons lined up 12 boys and men and gunned them down in El Limoncito, a tiny village in the Pacific Coast state of Sinaloa--a massacre attributed to a drug turf war.

A few months later, at a broadcasters’ convention in Sinaloa, the birthplace of Mexico’s most famous traffickers, radio owners announced they would no longer play narcocorridos in the state.

“If they could do it there,” Mayans reasoned, “there was no reason we couldn’t do it in Baja California.”

Last December, the Mexican Senate exhorted states to restrict narcocorridos, saying the songs “create a virtual justification for drug traffickers.”

Influence on Teens

In January, Chihuahua legislators adopted a nonbinding resolution asking radio stations not to play the songs, calling them a siren call to a life of “violence, criminality and drug trafficking” that “teenagers imitate to the detriment of society.”

Consensus in Baja California jelled in July. Broadcasters gathered in a tastefully understated salon of the Hotel Lucerna and signed the pact.

“It’s not an obligation or a censorship. It’s voluntary,” Mayans said.

Programmers agreed to support Mexican traditions, and “the narcocorrido is not a Mexican tradition,” he said. “The narcocorrido is an apology for violence.”

But the lingering mystique of the narco-pose was all too evident on a recent night at the “Cowboy Bar” on Avenida Revolucion in Tijuana. Onstage, the dashing, mustachioed Roman Coronado sang about a Mexican federal policeman who defected to work for the drug cartel.

“Give me a line of coke,” Coronado sang. “I was once a federal agent, but it did me no good, because the Mafia was too numerous, and the police too few.”

When four glowering young men swept into the bar, patrons got out of their way. Waiters tripped over themselves to provide the sullen quartet with Remy Martin. Women whispered: Who are they?

“It’s narco-fashion,” acknowledged one of the mystery men, Luis Esquivel, 23, resplendent in canary yellow ostrich skin boots and a red leather coat, while his three companions sported black leather and enough gold jewelry to reduce the national debt.

“It’s all about trying to act like narcos, drug dealers, to get respect,” said Esquivel. “I like to give that impression. You get the girls’ attention right away.”

The real life of this electric cowboy is more banal: Esquivel is a San Diego community college student.

“It’s more the younger generation that likes narcocorridos,” Esquivel said. “It’s like rap and hip-hop. A lot of the corridos are associated with drugs and Mafia in Tijuana ... They see big-time Mafiosos living a fantasy, doing whatever they want.”

Another musician at the bar, Abel Guzman, sings a favorite narcocorrido, about a drug cartel gunman who is called before his godfather boss to sputter out his denial of involvement in the notorious torture-murder of a U.S. anti-drug agent.

“The death of Enrique Camarena is a legend, so it became a corrido,” Guzman explained. “If someone is killed, people write a corrido about it, and his death becomes history. That’s why people love corridos.”

For hard-core fans, paramilitary kitsch seems part of the appeal.

The album cover of “Mi Oficio es Matar”--”Killing is My Business”--shows singer Jesus Palma with a bazooka. Fabian Ortega--”the Falcon of the Sierra”--dressed up his album cover cowboy look with an AK47 assault rifle.

Narcocorridos eschew the crowing roosters and barnyard sounds of ranchera music for more urban atmospherics--sirens, gunfire and helicopters.

Art, Life Intersect

The industry is rife with rumors of relationships between musicians and traffickers.

Some balladeers have stumbled over the line between art and life, and become the victims of the violence they portray.

Rosalino Sanchez, a poor Mexican immigrant in Los Angeles, rose to fame as a narcocorrido star--”Chalino”--whose street “cred” was enhanced by the pistol he wore in his belt and the gunman who wounded him onstage near Palm Springs.

In 1992, when the 31-year-old singer returned to his home state of Sinaloa, he disappeared after a concert. His bullet-riddled body turned up later on a roadside.

A few years later the genre exploded into the mainstream.

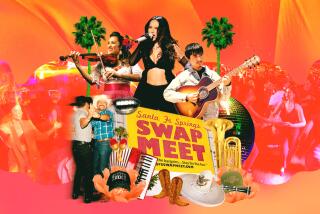

By 1997, the composers of some of the most memorable narco-ballads, Los Tucanes of Tijuana, had more hits on the Latin Billboard chart at the same time than any artist since Selena. Reviews of Tucanes videos of that era described scenes of a policeman being shot and another being tortured--presumably by drug traffickers.

Tucanes’ lead singer, Mario Quintero, said the narcocorrido radio blackout “is not the solution.”

“The movie ‘Traffic’ is like a corrido made into a film, but obviously you can’t prohibit a movie,” he said in an e-mail from Acapulco.

“Prohibiting narcocorridos will not solve the problem.”

But in Baja California, “the problem” is a particularly touchy subject.

Nearly everyone in high-end Tijuana knows someone with onetime links to the Arellano Felix crime family.

Priests baptized their children. Businessmen “borrowed” money from them. Public officials sold land to them. Local families intermarried with them. And radio stations played songs about their exploits.

“It seems hypocritical that the people who created the market for narcocorridos, who popularized them, now want people to stop listening to them,” said Victor Clark, the respected director of Tijuana’s private Binational Center for Human Rights.

“Prohibiting them will just turn them into the forbidden fruit,” he said. “Narcocorridos are deeply established now in the popular culture of northern Mexico.”

Yet radio stations have gone along with the ban. Some listeners call in to register their disappointment--but others just tune in to narcocorridos broadcast from stations north of the border.

“There are a lot of stations in Southern California that play [narcocorridos], and they are high-powered enough to be heard in Tijuana,” lamented Gloria Enciso, of Tijuana’s Radio Enciso. “They should ban narcocorridos from the recording studios.”

There’s no sign officials will try to remove the forbidden music from the honky-tonks where it first emerged.

City patriarchs might publicly support the radio initiative, but more than a few of them own nightclubs where narcocorridos are still popular--and profitable.

“Patrons like them. They request them,” shrugged Manuel Rodriguez, 30, a waiter at the Cowboy Bar. “It’s not the ballads’ fault there’s so much drug violence.”

*

Times staff researcher Robin Mayper contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.