Is It a Teardown or a Treasure?

Jeffrey and Karen Brandlin searched for two and a half years to find the perfect spot to build their dream home. They finally found it in a double lot in Brentwood where a small home already stood.

But the house they purchased was no ordinary home: It was a Neutra. And preservationists were not going to let them replace the work of Richard Neutra, considered a master of Modernist architecture, without a fight.

The Brandlins found themselves embroiled in a debate that stems from a question: Should every structure designed by a prominent architect be saved? As the demand for new and bigger homes and schools threatens a variety of pedigreed buildings, the question is being asked more often.

“How much of the past do we have to preserve?” wondered Maureen F. Gorsen, an attorney representing the Brandlins. To preservationists, “every one is like the Alamo.”

The controversy surrounding the Brandlins comes in the wake of demolitions in recent years of several homes by noted architects, including Rudolph Schindler’s Wolfe House on Catalina Island and his Packard House in San Marino. But it was the leveling last year of the Neutra-designed Maslon House in Rancho Mirage by a Minnesota couple that set preservations and others howling.

After preservationists learned the Brandlins had obtained a demolition permit, the Los Angeles Conservancy nominated their home, known as the Maxwell House, for listing as a city historic-cultural monument. The designation could allow the City Council to delay demolition by up to a year and trigger an environmental review.

Some cities in Southern California, however, lack a legal framework to preserve homes and “many of the most significant examples of residential architecture have no protections,” said Ken Bernstein, the conservancy’s director of preservation issues.

At the same time, Bernstein added, numerous designs by pioneering modernist architects are only now turning 50, making them easier to list. Properties less than 50 years old must demonstrate “exceptional significance” to be added to the National Register of Historic Places.

The Getty Conservation Institute is trying to lay groundwork for a comprehensive citywide survey of historic resources that could identify significant structures. For now, determining the importance of unlisted buildings is not an exact science, since one person’s architectural treasure is another’s teardown.

Take the Morris Landau Residence in Holmby Hills. The Harvard-Westlake School has proposed expanding its middle school campus by leveling the home designed by Paul R. Williams, who became the first African American member of the American Institute of Architects in 1923.

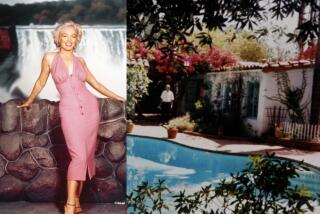

In an era when he was not welcomed in many of the buildings he conceived, Williams taught himself to sketch upside down so he could sit across from white clients to convey his ideas without threatening them. He designed about 3,000 structures, including the First AME Church in South Los Angeles and homes for Frank Sinatra and Lucille Ball.

Marcia Selz, president of the Holmby Hills Homeowners Assn., described the Landau Residence as “almost melodic.” The approximately 10,000-square-foot, two-story home features a partial brick exterior and an elegant interior with a curving staircase, rich moldings and plenty of windows.

“We believe the school is degrading the neighborhood by destroying this absolutely glorious residence by Paul Williams,” said Selz, whose group recently nominated the home for monument status. “The homeowners in our association revere his work.”

John Amato, assistant headmaster of Harvard-Westlake, said the school would like to replace the residence with a new administration building, library, technology center, science classrooms and, to reduce traffic backups on North Faring Road, more than double the driveway.

“We don’t think the way to have this discussion is to disagree with cultural significance,” said William F. Delvac, an attorney representing the school. “That’s not our concern. Our concern is educating kids.”

An environmental impact report, which is being prepared by the city, will consider the project’s effect on the Landau Residence and a school administration building -- the last original structure from the former Westlake School for girls -- which Selz’s group also nominated for monument status.

While some preservationists might argue that every structure by a prominent architect is worth saving, Karen Hudson, Williams’ granddaughter, suggested such decisions should be weighed individually. Other threatened work by Williams includes the landmark Ambassador Hotel, where he redesigned the hotel coffee shop and the Embassy Ballroom.

The Los Angeles Unified School District is studying the property as a potential site for new schools, but has not yet made a decision.

“My grandfather would be the first person to put education ahead of a ballroom,” said Hudson, who included photos of the Landau Residence and the Ambassador Hotel in her book, “Paul R. Williams, Architect: A Legacy of Style.”

“On the other hand, I look at it from the standpoint of we’re raising a generation of children who I don’t think have an appreciation for the history of our city.”

But a hotel is different from a home, such as the Maxwell House, owned by a private family, the Brandlins, who must absorb expenses caused by the nomination. The Brandlins paid $1.6 million for the 1,700-square-foot home on a huge lot of more than 13,000 square feet.

While the couple, who want to build a contemporary, 5,300-square-foot residence, acknowledge that real estate agents told them the home was designed by Neutra, Jeffrey Brandlin said, “We didn’t realize the significance of it.”

Gorsen, their attorney, said her clients are like many home buyers who have no knowledge of architecture and historic preservation. “They are not subjects with which the average homeowner is familiar or may have even an amateur interest,” she wrote in a letter to the Cultural Heritage Commission.

Apparently the city of Los Angeles was also unaware of the property’s significance, since the Department of Building and Safety issued the Brandlins a demolition permit in March.

In the August nomination of the Brandlins’ house, the conservancy described Neutra as a pioneer in contemporary architecture who did his most distinguished work from Los Angeles, his adopted home.

Originally designed for musicians Charles and Sybil Maxwell, the house is an early example in which Neutra used a pitched roof in deference to zoning codes as well as his musician clients’ dislike of low ceilings, according to Thomas Hines, a professor of history and architecture at UCLA and author of “Richard Neutra and the Search for Modern Architecture.” Preservationists note that it was also an early Neutra home to feature wood siding, which became a common architectural motif in post-World War II homes.

Neutra judiciously and astutely linked house to site, a reason preservationists would like to see the home remain at its present location, according to Barbara Lamprecht, author of “Richard Neutra -- Complete Works.”

“For Neutra, every second of your life was important,” Lamprecht said. “If you had a huge kitchen and spent 15 steps to get from your Sub-Zero refrigerator to your stove, that was time out from a life that should have been lived with intelligence.”

Built in 1941, the Brandlins’ home features clean lines and a large sliding glass door that opens onto a flagstone terrace and a sprawling yard. After obtaining a demolition permit, the couple was contacted by Lamprecht, who urged them to find a new architect or move the home, among other suggestions.

The Brandlins said their designer interviewed an architect specializing in Neutra additions, but were told his fees would top $1 million and he would decide the design.

The couple even agreed to let others, including an architect, videotape and then dismantle the home, storing its Neutra-significant components for reconstruction at another site.

Then, on Aug. 21, the Brandlins received a fax telling them the city had stayed the demolition permit. Soon after, while vacationing in London, they received word that the Cultural Heritage Commission wanted to inspect the home in early September because it had been nominated for monument status. The couple, who would have been out of the country, objected.

In mid-September, after the Brandlins had returned to Los Angeles, four commissioners briefly toured the property, taking special note of a built-in desk and the landscaping.

“To let a Neutra house go down without an attempt to preserve it, we would be criticized throughout the country,” said Michael A. Cornwell, president of the L.A. Cultural Heritage Commission, after the inspection.

“We’re not ill-hearted,” countered Jeffrey Brandlin. “We’re not mean people who want to destroy something. We just don’t like you coming and telling us what we have to do.”

The commission, on the spot, voted unanimously to recommend the home for monument status, sending it to a City Council committee for a hearing. If it clears the committee, the case would be forwarded to the full council.

Catherine Barrier, a preservation advocate for the conservancy, offered to help the couple find another architect sensitive to Neutra or a new buyer. A survey by her group of Neutra’s work in Los Angeles has found fewer than 50 single-family residences that have not been extensively remodeled or demolished.

Jeffrey Brandlin said he and his wife are considering selling the home. On Friday, representatives from a museum and a local university interested in moving the house swung by to take a look.

It was an encouraging sign, but the couple wonder why, if the home is so significant, it was not already listed as a monument -- a designation they certainly would have taken into consideration when house-hunting.

“It would have been nice to specify so you know what you’re buying,” Karen Brandlin said.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.