Bush’s march to war

Plan of Attack

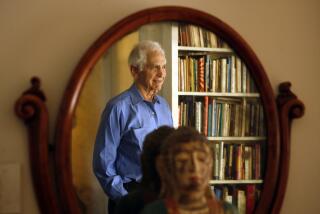

Bob Woodward

Simon & Schuster: 443 pp., $28

*

National polls published this week report that Americans likely to vote in the next presidential election say that a candidate’s stands on terrorism and the war in Iraq are more important than their positions on the economy, education or healthcare.

That shift in interest accounts for part of the extraordinary buzz that has surrounded “Plan of Attack,” Bob Woodward’s engrossing and astonishingly detailed reconstruction of how President Bush reached his January 2003 decision to launch an unprecedented preemptive invasion of Iraq and to overthrow Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship. In still larger measure, the attention given this book since snippets of its content began to leak late last week is justified by the work itself.

“Plan of Attack” is a remarkable book, one that fulfills the too often ephemeral promise of what has come to be called investigative journalism. What Woodward has delivered is not so much a first draft of history but history in real time. Other writers and scholars proceeding at a more deliberative pace surely will add vital details and illuminating insights to this account, but they will just as surely take this book as their starting point. The American people seldom have been given this clear a window on their government’s most sensitive deliberations, with the opportunity to pass judgment on what they see still before them in November. Anyone who goes to the polls without becoming familiar with this book’s contents and forming an opinion about their significance risks dereliction in the exercise of his or her franchise.

Readers will find it necessary to draw their own conclusions about this story’s implications, because of Woodward’s scrupulous adherence to certain journalistic conventions. This is a narrative rich in exotic detail and vivid characterizations, but virtually devoid of judgments. Many will find that frustrating; others will agree that reporters necessarily forswear their right to judge so that others may truly exercise theirs. Moreover, while “Plan of Attack” has a propulsive narrative structure, Woodward’s prose can charitably be described as utilitarian. (Anyone who has followed the careers of Woodward and Carl Bernstein since their collaboration on the compellingly written “All the President’s Men” by now has formed a pretty clear notion of Woodstein’s division of labor.)

Last weekend, the Washington Post, where Woodward is an assistant managing editor, published extensive excerpts from the book. Before and since its official release Monday, the author has been a ubiquitous television and Internet presence. Thus, “Plan of Attack’s” most newsworthy revelations are, by now, fairly well known:

* On Nov. 21, 2001, long before he ostensibly decided on war, Bush instructed Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld to update contingency plans for an attack on Iraq.

* At least $700 million in funds appropriated by Congress after the Sept. 11 attacks for the war against Al Qaeda and its Taliban allies in Afghanistan were diverted without legislative approval to finance preparations for an attack on Hussein.

* Bush’s Cabinet was divided between Secretary of State Colin L. Powell and his aides, who opposed war, and Vice President Dick Cheney, Rumsfeld and his circle of neoconservative advisors, who came into office spoiling for another go at Iraq.

* On Jan. 11, 2003, Cheney, Rumsfeld and Gen. Richard B. Myers, chairman of the Joint Chiefs, met with Prince Bandar bin Sultan, Saudi Arabia’s ambassador to the U.S., and showed him essential details of the war plan. Bandar’s principal concern seemed to be that, this time around, the Americans wouldn’t kill Hussein. Cheney assured the prince that the Iraqi strongman was “toast.” Bandar casually mentioned the Saudis’ hope to increase oil production so as to hold gas prices down before the election. He requested and received a subsequent meeting with Bush. Powell had yet to hear of the plans for war.

*

Tsunami of disclosure

For an administration that has prided itself on its internal discipline and lack of leaks, Bush’s government has spawned an unusual number of astonishingly detailed “insider” books. (It’s almost as if some pent-up demand that would not be denied ultimately produced a tsunami of disclosure.)

First came Woodward’s own bestselling “Bush at War,” which portrayed the post-Sept. 11 president as an unexpectedly resolute and sober leader. The chief executive’s satisfaction with that portrait led him to suggest this new volume to Woodward and to make himself available for an unusual series of taped, on-the-record interviews. He also instructed 75 members of his administration to make themselves similarly available.

Since then, three other volumes of importance have appeared -- Ron Suskind’s “The Price of Loyalty,” drawn from dismissed Treasury Secretary Paul H. O’Neill’s recollections; former White House antiterrorism advisor Richard A. Clarke’s “Against All Enemies,” which alleges the administration was insufficiently attentive to Al Qaeda; and James Mann’s “Rise of the Vulcans: The History of Bush’s War Cabinet,” which documents the fundamental influence of the neoconservatives.

All three have been vigorously attacked by the White House and its allies. However, Woodward’s narrative of the march to war uses administration sources to corroborate the essential thesis of all three: that the Bush team arrived with an obsessive fixation on Hussein, that it initially discounted the threat from Al Qaeda and that it was excessively in thrall to the neoconservatives’ vision of a muscular new Wilsonianism that would spread democracy at the point of a gun.

Two vignettes that Woodward reports from the pre-inauguration period are particularly telling. In early January 2001, he writes, Cheney “passed a message to the outgoing secretary of Defense, William S. Cohen, a moderate Republican who served in the Democratic Clinton administration.

“ ‘We really need to get the president-elect briefed up on some things,’ Cheney said, adding that he wanted a serious ‘discussion about Iraq and different options.’ The president-elect should not be given the routine, canned round-the-world tour normally given incoming presidents. Topic A should be Iraq.”

A few days later, Bush, Cheney and national security advisor Condoleezza Rice were secretly briefed by CIA Director George J. Tenet and his deputy for operations, James L. Pavitt. They told the incoming president and his two closest security advisors that there were three major threats to American national security. One was Osama bin Laden and his Al Qaeda terrorist network, which operated out of Afghanistan. The other threats, Tenet and Pavitt, said, were the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, although they conspicuously failed to mention Iraq in that context, and the military rise of China, “but that problem was five to 15 or more years away.”

The atrocities of Sept. 11 would follow, and within days, Bush, Cheney and Rumsfeld were pushing for anything that would link Hussein to the attack. When Tenet subsequently briefed the president on the CIA’s by-then firm opinion that Baghdad possessed weapons of mass destruction, Bush -- who invariably displays a particular shrewdness toward political questions -- called the presentation “not something that Joe Public would understand or would gain a lot of confidence from.” Tenet proclaimed the case “a slam dunk.” No one seems to have asked why such an open-and-shut case wasn’t made in that pre-inaugural briefing.

Silence, as it turns out, played a pivotal role in the Bush administration’s deliberations. The president never asked Powell or any other advisor whom he knew harbored reservations about renewed military action in Iraq whether they thought it was a good idea to go to war. Powell, who believed Cheney had a “fever” when it came to Hussein and thought the neoconservatives’ proposals were plainly “lunatic,” never offered his president the opinion for which he was not asked.

Those who come to “Plan of Attack” hoping to find the moment when the president of the United States went around the table and asked his Cabinet and advisors whether the nation should go to war, will not find it. It did not occur, and none of them demanded it. Instead, a highly selective search for advice and a series of maneuvers that made conflict inevitable produced an irresistible slide into conflict. Whether this is the ethic of bureaucracy or steely statesmanship is one of the conclusions on which readers will differ.

The same polls that show terrorism and Iraq rising to the top of prospective voters’ concerns also show that Bush’s approval rating has easily weathered the storms of the last month (further disintegration of the military situation in Iraq and rising American casualties, the hearings of the Sept. 11 panel, the disclosures in Clarke’s and Woodward’s books). It seems likely that readers will take from Woodward’s splendid narrative pretty much what they brought to it, either a belief that the war in Iraq could not have been avoided or a conviction that it was a tragic national mistake.

Point in fact: This week, the official websites of both Sen. John F. Kerry of Massachusetts, the presumed Democratic nominee, and the campaign to reelect Bush/Cheney included “Plan of Attack” on their lists of recommended reading.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.