A Steep Fall Into Gang Life

At 16, he was a top student, star athlete and police Explorer.

At 21, he was a Crip bent on avenging a murder.

How one black teenager, nicknamed Gizmo, went from promise to catastrophe in a few years reveals the complicated relationship between African Americans and the Los Angeles Police Department in the city’s most violent neighborhoods.

Police in South Los Angeles mix it up with the same people all the time, mostly young black men. They alternate between friendly persuasion and ruthless confrontation, tactics they say they used to try to save Gizmo. His family says they only made things worse. Both sides describe a relationship that was tense, emotional and strangely intimate.

As with many South L.A. stories, this one begins with a bullet.

Gizmo was shot walking home on a spring morning in 2001. He was 16, advanced in high school for his age, and two weeks shy of graduation. The gunmen were gang members from another neighborhood.

He tried to run, but made it only as far as two parked cars. He crouched between them and listened to bullets hiss by his ear. “Sip, sip, sip,” he said, recalling the sound. One clanged against metal, inches away. Then something slammed his body forward, and he went numb.

He was lucky. The bullet damaged organs but didn’t kill him.

Among the first to visit him in the hospital was Officer Gary Beecher.

Beecher, 38, ran youth programs in the LAPD’s Southwest Division, and had recruited Gizmo to the Explorers.

A former outfielder once drafted by the Angels, Beecher was a seasoned patrolman who had worked gang units.

He has also worked with hundreds of black and Latino youths in South Los Angeles as a coach and as a volunteer in sports leagues.

Gizmo was among Beecher’s favorites.

“A super kid,” the officer said. “He always went above and beyond what I told him to do. Always, ‘Yes, sir, what do you want me to do next?’ ”

Recovering in the hospital, the bullet still inside him, Gizmo told Beecher that LAPD investigators had asked him to identify his attacker.

Gizmo was reluctant -- loath to be known as a snitch.

Beecher urged him to cooperate.

Are you a gang member or not? the officer asked.

A Model Student

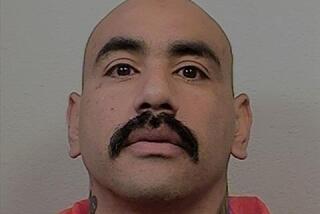

Gizmo was slim, with very dark hair and skin, large, wide-set dark eyes, and a way of tilting his chin high when he spoke. He was sharp, a fluid talker full of lithe, quick movements -- always busy and darting soundlessly around the house.

As a toddler, he had been tiny for his age, and family members borrowed his nickname from that of a very small toy. As Gizmo grew up, he remained slight, but was superbly agile, a sprinter and natural baseball player who was also a model student.

He had a half brother, five years younger, whom the family called “Red” because of his light, ruddy skin and red hair. Red had more brawn than Gizmo and was also more gregarious and defiant. Unlike his studious older brother, Red hated school.

(Gizmo and members of his family insisted that the brothers’ full names not be used and that their mother and grandparents remain anonymous. They said they feared further violence from gang members if their identities were revealed.)

Children of a single mother and absent fathers, the boys were raised by their grandparents -- a retired teacher and aerospace worker. The family thought it best to raise the boys in a two-parent home; their mother visits daily.

The elderly couple were devoted to the boys. They took them on fishing expeditions. Sports trophies, dozens of them, accumulated six deep in the couple’s living room.

The grandparents were delighted when, at age 14, Gizmo told them he wanted to be a police officer. They signed him up as an Explorer at Southwest, which neighbored the 77th Street Division where they lived.

LAPD Explorers is an educational program for teenagers interested in law enforcement careers. Beecher thought Gizmo a great candidate.

And the grandmother welcomed Beecher into the family. “A loving person,” she called him. She felt she and Beecher shared a goal: to steer Gizmo away from the local gang, a subset of a larger gang and consisting of about three dozen young men.

Gizmo couldn’t walk out his front door without seeing one of the gang, Beecher said.

“You live in that neighborhood, you are going to be associated with them,” he said. “You’ve got to say, ‘Hi,’ to them or they’re going to kick your ass.”

Being an Explorer took courage. The toughs called him blue boy, police flunky.

But he seemed impervious. He was a college-bound baseball infielder at Manual Arts High School and took weekend Advanced Placement courses at USC. He was named the Southwest Division’s outstanding Explorer recruit.

His grandmother treasured that trophy above the others, giving it a special place in front of the piano.

As Gizmo lay in his hospital bed, Beecher told him he was confronted with a choice: Testify, and demonstrate that he was not a gang member, or decline, as gang members nearly always do. The teenager understood.

He was a not a gang member, he told the officer. He would help the police.

Gizmo identified his attacker and was ordered to appear in court. In the hallway, he found himself facing his assailants’ angry friends and relatives. He felt keenly aware of the difference between himself and the officers standing with him, he said. Police had the protection of their uniforms. He was just another black teenager.

His attacker was convicted. But Gizmo said he walked out feeling scared and alone. It dawned on him that cooperating with police involved far more danger than he realized. He had considered the police his friends. Now, members of his family said, he felt betrayed by police and endangered by a legal system that seemed indifferent to his safety.

Already he had been shot, and threats had always been part of life in his neighborhood. But after testifying, he said, “I felt I was targeted.” Gang members would confront him and say, “We heard about you.”

Gizmo became “like a different person,” his grandmother said. He seemed withdrawn, gave up his dreams of college ball and was angry at the police.

Beecher had hired Gizmo as a youth football official the fall after the shooting, but lost touch when the season was over. He thought the youth had moved on, the way Explorers do when they graduate -- as Gizmo did -- from high school.What Beecher didn’t know was that Gizmo was becoming involved with a different arm of the LAPD: The 77th Street Division’s gang detail.

Gizmo had finally joined the local gang.

Terrified of Retaliation

Gizmo’s grandfather has a thick mustache and favors crisp shirts. The grandmother is a small woman with large eyeglasses and long, glossy black hair, pulled back in barrettes.

The couple are from Arkansas. Both are in their late 70s and in poor health; Gizmo’s grandmother uses a cane.

The family lives off the Harbor Freeway in a neighborhood of run-down houses and pretty ones side by side -- a pile of mattresses here, a hedge of canna lilies there.

The grandmother said Gizmo was terrified that the rival gang would kill him for testifying, so he began carrying a gun and sought protection from the neighborhood gang. Red followed his brother’s path.

Red, always more difficult than Gizmo, was arrested in a car with gang members seven years older, guns and ski masks in the trunk. He was placed on felony probation.

Gizmo was arrested with a gun and also given probation.

“Would you rather get caught with a gun and get jail for a year, or get caught without a gun and get killed?” he said.

The brothers began to get stopped regularly by police. Probationers can be searched without cause, and three or four times a day Gizmo or Red would be outside or on the way to the store, and officers would demand that they lift their shirts to show whether they were hiding weapons. Or police would order their hands on their heads and pat them down. If the brothers stepped into the street, they got jaywalking tickets.

Each time they were stopped, the grandmother said, the brothers seemed angrier, more contemptuous of authority. She was beginning to feel that the stops were undermining her efforts to straighten them out. Gizmo would no longer listen to her. He refused to talk to Beecher, and he told his grandmother that he now hated police.

Police “embarrassed and humiliated them for no reason in front of the neighbors,” she said. “I’m not defending the wrong things my kids did. I know they did wrong things.... But we needed help. And the police weren’t helping.”

Meanwhile, she said, officers never seemed to catch the neighborhood’s violent predators.

Police said they were not stopping Gizmo and Red to harass them, but to prevent crime.

Such tactics may draw community anger, said LAPD Det. Will Beall, but the 50 homicides in the 77th Street Division so far this year “are not a figment of the racist imagination.”

Asked if frequent searches were an effective deterrent, LAPD gang detail Officer Greg Martin of 77th Street said: “Sometimes ... maybe on an hourly basis.”

There was another reason why police paid so much attention to Gizmo and Red.

They allege that the pair terrorized neighbors. Police said they could not persuade neighbors to stand up as witnesses against the brothers, so they used stops and searches to let the pair know they were being watched.

The tactics reflected an odd condition of high-crime neighborhoods: many unsolved crimes but few mysteries. Police and residents often have a good idea who the criminals are, but the offenders seem untouchable.

Residents are angry with police for not catching the shooters. Police are angry at residents for not identifying them. To some officers, it seems as if neighbors were colluding with gangs. “A mass Stockholm syndrome,” one 77th Street detective said.

Police dismissed the grandmother’s claim that they hastened Gizmo’s fall. “It’s an excuse,” one detective said.

Lousy parenting is to blame, snapped another detective. “The police can’t be in every hallway, every boy’s room,” another said.

Despite the friction, each side spoke of the other with familiarity and emotion. Most people in the rest of the city rarely come into contact with police. But Gizmo’s grandmother can tick off the names of 77th Street officers. She knows their ranks and assignments. Officers, in turn, refer to members of the family by first names.

In conversations, the grandmother maintained that police often used threatening, childish and callous language with Gizmo and Red. “ ‘I hope they get you,’ ” she alleged that one officer said.

Police deny saying that, but they admit taking a tough line, predicting that the brothers would be murdered if they didn’t shape up.

“Our perceptions and their perceptions are never matched up,” said LAPD gang Officer Grace Garcia.

Distrustful of LAPD

When the brothers’ growing profile started drawing assaults by rival gangs, the grandparents wanted to leave. But they lived on a fixed income in a house they had owned for decades, and they couldn’t afford to start over, the grandmother said. She also wasn’t sure that she could persuade Gizmo to move away from the gang.

Earlier this year, Det. Beall offered to enroll the family in the state’s relocation program for crime witnesses if they would testify about one attack on the family. The program provides a small sum for rent and moving expenses. Take the deal, he urged them, “or your boys will end up dead or in prison.”

But the family no longer trusted the LAPD.

In March, Officer Garcia and her partner scuffled with Red, now 15, who ran inside and locked the screen door when they tried to search him.

Later, as police searched the brothers’ room, the grandmother followed them and was escorted out. They say they did it gently; she said roughly.

“One of the officers grabbed my wrist and twisted it,” she said. “I said, ‘What I look like? I can’t hardly walk, can’t hardly move!’ ”

In early May, Red was sitting on his front porch on the red ice chest that his grandfather used when they went fishing.

A carload of rival gang members sprayed the house with AK-47 bullets. Red stumbled inside and collapsed. Gizmo stared at the wound in his brother’s side -- “big enough to put a spoon in,” he said -- and begged him to speak.

Red died. Later, filled with grief, Gizmo stormed around the crime scene, calling for retribution loud enough for police to hear.

Det. Beall heard of Red’s death by phone at home. He felt a rush of hopelessness. He spent the rest of the afternoon, he said, “stalking around the house.”

LAPD Det. Scot Williams recalled Red’s body laid out on a stainless steel autopsy table:

His tattoos were those of an adult, he said, a hard-core gang member. Red may have been just 15, he recalled thinking, but “this is not a little kid.”

What Went Wrong?

Gizmo remains at his grandparents’ house. Police believe it likely that someone will kill him too, or that he will avenge Red.

A central question remains: Why did Gizmo slip?

A number of officers said they were sure that his gang involvement began before he testified in court and that he had lived a double life.

But Beecher, the officer who recruited Gizmo into the Explorers, said he believed that the truth was more complex. He recalled Gizmo often telling him that he had a plan to escape the neighborhood: a full-time job, college and an apartment far away. But as Gizmo got older, he confided to the officer that he didn’t think he had the means.

Beecher said he couldn’t know for sure but thought Gizmo put up a valiant fight. “In that environment,” he said, “it’s like he had no other choices.”

Gizmo said no one had it quite right. Not the police. Not his grandparents.

He did join the gang after he testified, he said -- partly for protection, partly to make money from selling drugs. But he was wavering long before. The gang members were his childhood friends. Whenever you want to come home, they told him often, you can come home.

Rival gang members, meanwhile, didn’t seem to care whether or not he was in a gang. They shot at him anyway.

So, although he concentrated on school and Explorers, inwardly he toyed with joining. He would have done it long before, he said, but for Beecher.

“He cared,” Gizmo said. “He was the one reason I even considered police work.”

After testifying, he said, “it was all over.”

He joined the gang at 17. He sold drugs, found the job boring, moved up, grew more ruthless. Beecher was no longer around.

“I thought, ‘I’m tired of running,’ ” Gizmo said. “I might as well be a part of it.”

After a while, he no longer felt fear when shot at.

Looking back, “gangbanging is a bad decision ... the mistake of a lifetime,” he said as he used a screwdriver to pry bullets from a door frame inside his grandparents’ house.

“But I can’t get out of it now. And I couldn’t tell you if I want to anymore.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.