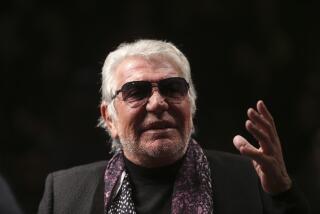

Carlo Mariotti, 76; Italian Stone Artisan Left His Stamp on Public, Private Projects Around the World

Carlo Mariotti, an Italian stone artisan whose travertine graces many of the world’s most recognizable buildings, including Getty Center and the new Walt Disney Concert Hall, died of cancer Thursday in a Rome hospital. He was 76.

Mariotti battled a series of cancers for 14 years, said Carolyn Hench, a Los Angeles representative of his firm.

Revered by architects for his charm and imaginative use of stone, Mariotti left his stamp on dozens of projects small and large, private and public, at home in Italy and abroad. He worked and became friends with such architects as I.M. Pei and the late Minoru Yamasaki, designer of the World Trade Center towers in Manhattan.

Most recently, Mariotti & Figli, as the Mariotti family’s fourth-generation business is known, provided stone for the new Bank of China headquarters in Beijing and the new UCLA hospital under construction on the southern end of the Westwood campus. In the 1990s, Mariotti also donated the travertine to repair the famed Spanish Steps in Rome.

“He really left his mark all over the world,” said L.C. “Sandi” Pei, a son of architect I.M. Pei and a partner in Pei Partnership Architects, which worked with Mariotti on the Bank of China and UCLA projects. “He set a standard that will be very difficult for people to measure up to. He really was a titan.”

Mariotti had “an openness and joy of living,” said Taro Yamasaki, Minoru Yamasaki’s son, whom Mariotti hired to photograph dozens of projects for two self-titled books about the Mariotti business.

Known for his gracious hospitality, Mariotti often invited architects and builders to his family villa in Bagni di Tivoli, 12 miles east of Rome.

In a recent profile in The Times, Mariotti described himself as a grateful patient whose life had twice been saved by doctors at UCLA. By way of thanks, Mariotti offered more than 3 million pounds of buff-colored travertine at a rock-bottom price for the new hospital. “I’m part of the veneer,” he said in a February interview at UCLA. The stone now encases the outside walls in the form of 15,000 panels.

While recovering at UCLA Medical Center from his first cancer, sarcoma, in 1990, Mariotti dreamed up a guillotine-like machine to split stone blocks along the stone’s bedding plane.

The effect so impressed architect Richard Meier, who designed the Getty Center, that he agreed to use the stone, with its rough, fossil-flecked finish, throughout his project. At the Disney Concert Hall, highly polished stone from Mariotti’s firm decks steps and floors.

Born on Oct. 1, 1927, Mariotti studied piano in Parma, Italy, as a young man. More mason than musician, he joined the family enterprise at 19.

One of his early assignments was finding the proper travertine for the classical obelisks that now flank the Via della Conciliazione, the concourse that leads from the Tiber River to St. Peter’s Square in Vatican City.

In 1955, Mariotti took on his first full-scale assignment in the United States, fashioning an arch and cornice for jeweler Harry Winston on New York’s Fifth Avenue.

In the 1960s, Mariotti travertine became the unifying force for the Lincoln Center complex in New York. The half a dozen high-powered architects who designed the various components had disparate views on building styles, but they all could agree on Mariotti travertine.

Mariotti, who called himself the Marble Man, had been honored recently with Italy’s Cavaliere del Lavoro, an award presented to citizens who have distinguished themselves in business.

Mariotti is survived by his wife, Stefania, known as Titti; four children, Carla, Fabrizio, Primo and Stefano; and seven grandchildren.

A funeral is planned for Saturday in Tivoli, Italy.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.