Freeing Lincoln

Frederick Douglass gave an Independence Day speech in 1852 titled “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” Good question. Racial slavery was the appalling contradiction at the heart of the early republic. Slavery’s unbridled tyranny mocked the American Revolution’s bedrock principle of human equality. One of every five Americans was a slave on July 4, 1776.

The statesmen who won the Revolution, drafted the Constitution and conducted the new government through its infancy could comfort themselves with the hope that their descendants would somehow achieve a gradual, peaceful emancipation. Instead, as the United States grew, slavery flourished and found ardent defenders. No longer did slaveholders lament slavery as a “necessary evil.” They began to celebrate it as a “positive good.” So mighty did slavery ultimately prove that its destruction required a second and more sweeping American Revolution, a vast civil war of unprecedented scale and catastrophic destruction. Emancipation was the great turning point of the Civil War.

On the morning of New Year’s Day 1863, the White House was thrown open for the customary reception. Any visitor willing to endure the line that snaked across the lawn could exchange New Year’s greetings with the president. Abraham Lincoln worked the crowd for two hours, shaking hands like “a farmer sawing wood.” By the time he finished, his huge right hand was swollen and trembling. And now he needed a steady hand. Waiting for him in his office upstairs was the final copy of the Emancipation Proclamation. Only his signature was required to proclaim millions of enslaved Americans “forever free.”

As he dipped his pen, the president fretted that a shaky signature might make it seem that he harbored doubts. Then, with an effort of will, he firmly inscribed his name. For Lincoln did not doubt the wisdom or the righteousness of the Emancipation Proclamation. He called it “my greatest and most enduring contribution” and “the central act of my administration and the great event of the nineteenth century.” Lincoln was right, of course. Emancipation is easily the most revolutionary and far-reaching national policy ever embraced by a U.S. president.

Yet, as Allen C. Guelzo writes in his fine new study, “the Emancipation Proclamation is surely the unhappiest of all Abraham Lincoln’s great presidential papers.” Guelzo traces Lincoln’s tortuous journey to emancipation and explains why the crucial document has been so sadly underrated. He does so in a brisk and elegant narrative that is likely to stand for some time as the definitive account of Lincoln’s noblest achievement.

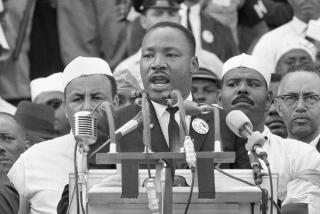

In 1963, when Martin Luther King Jr. gave his “I Have a Dream” speech beneath the brooding gaze of the massive statue within the Lincoln Memorial, he extolled the Emancipation Proclamation as the “momentous decree [that] came as a great beacon of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice.” Today, that momentous decree is being passed off as a monumental fraud, and the Great Emancipator is often portrayed as a cynical manipulator. The Emancipation Proclamation now seems best known for what it supposedly did not do.

Those who discount Lincoln’s boldness and moral urgency simply do not understand slavery’s baleful dominion over antebellum America. The slaveholders’ political power had long seemed unassailable. During the years from the birth of the nation until Lincoln’s 1860 election, the slaveholders and their Northern allies kept a stranglehold on the national government.

Nevertheless, the new counter-myth of emancipation charges that Lincoln, personally indifferent to the evil of slavery, was at best a reluctant liberator. The cagey politico grudgingly turned to emancipation only after the struggles of abolitionists in the North and freedom-seeking slaves in the South left him no other choice.

During his early career, after all, Lincoln had never made common cause with the abolitionists, who demanded an immediate, unconditional end to slavery. When the Civil War broke out, the new president quickly declared that the North was fighting to save the Union and not to free the slaves. He didn’t get around to emancipation until 1862, 1 1/2 years after the fighting started, and even then he delayed its implementation until 1863. And Lincoln’s proclamation applied only to those parts of the South still in rebellion; it left slavery intact in the loyal slave states and regions held by the U.S. military. In other words, the executive order applied only in places where the executive had no enforcement power -- an apparent contradiction that has given rise to the wrongheaded slur that the Emancipation Proclamation did not free a single slave.

To add insult to injury, the proclamation’s language is painfully turgid and legalistic. Lincoln was one of the finest prose stylists of 19th century America. Surely if he had really cared about the slaves, the writer who gave us the luminous cadences of the Gettysburg Address and the eerie grandeur of his second inaugural address could have thrown a few inspiring passages into his most important state paper.

By demolishing these misconceptions, Guelzo goes a long way toward restoring Abraham Lincoln to his proper place as the master spirit of emancipation. Easiest to dismiss is an alleged indifference to the brutal labor system Lincoln called a “monstrous injustice” and a “vast moral evil.” “I am naturally anti-slavery,” he once said. “If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong. I cannot remember when I did not so think, and feel.”

Just as preposterous is the notion that the Emancipation Proclamation was somehow ineffectual. It handed down a death sentence to the 250-year-old institution of American slavery. That the sentence took more than two years to execute completely (slavery was unconditionally outlawed in December 1865 by the 13th Amendment) in no way diminished its finality. The document’s lack of literary felicity is irrelevant. Guelzo reminds us that, unlike Lincoln’s celebrated speeches, the Emancipation Proclamation was a legal document and “legal documents cannot afford much in the way of flourishes. They have work to do.”

Guelzo’s book also succeeds in restoring emancipation to its historical context. Lincoln was the embattled and highly unpopular president of a democratic nation fighting for its survival. His seemingly slow progress was a measure of the difficulties he faced. He was struggling to hold together a fragile coalition. In 1862, he had reason to fear a military coup d’etat by proslavery generals in the Union army. He was afraid that moving against slavery would push the border slave states into the arms of the Confederacy.

Lincoln also knew that much of the white population of the North was bitterly prejudiced against African Americans. The president thought that the Northern war effort could be fatally damaged if he appeared to be a champion of black freedom. When freedom came, it must come as a war measure, not a humanitarian crusade. Lincoln moved toward emancipation just a step or two ahead of the people; he never moved fast enough to threaten their commitment to Union victory. It was probably the most brilliantly crafted performance in American political history. Guelzo has provided the best account to date of the political virtuosity and unswerving idealism that gave Lincoln his victory in the difficult battle to destroy slavery.

Long ago, in a far smaller compass, the greatest African American leader of the Civil War era voiced a comparable judgment. By 1876, Frederick Douglass, once a fierce critic of Lincoln and always a man deeply suspicious of white America, had concluded that: “From a genuine abolition point of view, Mr. Lincoln seemed tardy, cold, dull, and indifferent, but measuring him by the sentiment of his country -- a sentiment he was bound as a statesman to discuss -- he was swift, zealous, radical, and determined.”

*

From Emancipation Proclamation:

Jan. 1, 1863

And by virtue of the power, and for the purpose aforesaid, I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free; and that the Executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons....

And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind, and the gracious favor of Almighty God.

In witness whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed.

Done at the City of Washington, this first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty three, and of the Independence of the United States of America the eighty-seventh.

-- Abraham Lincoln

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.