Rampant Piracy Threatens to Silence Latin Music Industry

MEXICO CITY — They have been compared to the Rolling Stones for their longevity and legions of loyal fans. They’ve sold tens of millions of albums in Latin America. Now the seminal Mexican rock group El Tri is getting dumped by its record label. The reason: Bootleggers are the only ones profiting.

Piracy is so rife in Mexico that the vast majority of the band’s album sales are illegal CDs peddled on the street. So although most anyone over the age of 13 knows the words to “Que Viva El Rock and Roll,” El Tri and its label, a division of Warner Music Group, rarely see a peso from those recordings.

“If we play somewhere on a Friday night ... by Monday it will be [for sale] in the subway,” said Alex Lora, the gravel-voiced front man for El Tri. “It is becoming a way of life.”

El Tri may be among the first big Mexican acts to lose a contract to piracy, but it may not be the last. Entertainment bootlegging is sweeping the globe, but nowhere has the landscape changed more quickly than in Mexico. An estimated six out of every 10 CDs sold are believed to be bootlegs, vaulting Mexico to the No. 3 spot worldwide, behind China and Russia.

But unlike those nations, Mexico has a long-established commercial industry that is getting pummeled in the process.

Music retailers are closing their doors, as sales last year plunged to $347 million, down 25% from 2002, dropping Mexico out of the world’s top 10 music markets for the first time in years. Recording industry employment has fallen by nearly half since 2000, and the government is losing more than $100 million annually in tax revenue.

Labels are culling their rosters of established acts and signing fewer new ones. Pirates have robbed musicians of so many sales that the Mexican industry last year slashed the standard for granting gold records by one-third to just 50,000 copies -- one-tenth of the U.S. threshold.

“It’s an economic crisis” for the industry, said Fernando Hernandez, director of the Mexican Assn. of Phonogram and Videogram Producers, known as Amprofon.

But Mexican consumers say record companies could learn a thing or two from pirates, who provide entertainment that’s fast, cheap, reliable and customized. Bootleggers have been known to provide special orders and speedy delivery to rival anything from the studios.

“We were always running with shackles on,” said Oscar Sarquiz, a former executive with music marketer Columbia House Co., which closed its Mexican operation in 2002. “You tell the pirates you want [a compilation of] the 12 best heavy metal groups, they’ll say, ‘Here you are.’ ”

The shadow industry has likewise become a major employer, providing jobs to tens of thousands of itinerant vendors who oppose any attempts to squelch their livelihoods. Mexican artists are wary of complaining too forcefully, lest they be perceived as greedy and indifferent to their struggling fans. Meanwhile, organized crime and corrupt cops are profiting handsomely from the trade.

It all adds up to a bootlegging juggernaut some fear may be unstoppable. Industry veterans who have watched legal music sales all but vanish in smaller markets such as Paraguay and Venezuela are shaken at the assault on one of the hemisphere’s giants.

“If you lose Mexico, you’re dooming the [Latin music] industry,” said Raul Vasquez, a former recording executive who is now the Latin American regional director of the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry, a trade group battling piracy. “We’re at a very critical point.”

Analysts say Mexico’s poverty, sluggish job market, lax law enforcement and 100 million consumers have created the perfect climate for piracy. The country’s ubiquitous street markets are crammed with cut-rate knockoffs of all types of merchandise. But purloined entertainment is especially coveted by pop-culture-savvy Mexicans, many of whom can’t afford to shell out $15 to $20 for a new release -- nearly a week’s pay for some in a nation where the minimum wage is less than $4 a day.

Music theft in the U.S. is largely digital, with consumers swapping computer files for personal use. In contrast, Mexico’s piracy is a gigantic commercial enterprise involving everyone from importers of blank discs and the plastic jewel cases to hold them, to factory workers in clandestine factories and an army of street vendors. This vast underground assembly line last year delivered more than 85 million illegal CDs to eager buyers, according to Amprofon.

The cost of entry is low, just a few hundred dollars for a CD burner and some blanks. And profit margins are fat. Bootleg discs are so cheap to produce that CDs selling on the street for as little as 6 pesos, or about 50 cents, can still fetch a 100% markup.

“There is a lot more competition than there used to be,” said Jesus Flores Delgado, a Guadalajara music vendor who has peddled a variety of products in his two decades on the streets. “But it’s a lot less work than selling tacos or something like that.”

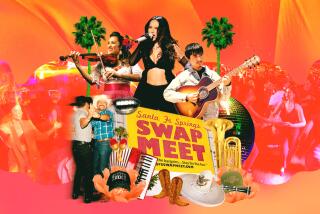

Though gangsters control production and distribution in some places, hawkers like Flores are everywhere. Far from a clandestine trade, pirated music and movies are sold openly on street corners and in public markets, often with stereos blasting to attract customers.

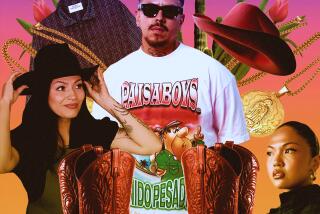

Latin artists are the most copied, from romantic crooner Luis Miguel to Long Beach’s own Lupillo Rivera, the bad boy of the narco-ballad. Still, Elvis Presley and the Beatles can be found in the humblest of stands. Young fans of alternative sounds flock to Mexico City’s Tianguis de Chopo market every Saturday to score the Sex Pistols and Marilyn Manson for a few dollars each.

Many of the finished products look amazingly authentic. The capital’s rough Tepito neighborhood, a notorious center for piracy, boasts an extensive wholesale section where bootleggers can stock up on blank discs, pilfered liner notes and plundered cover art as easily as if they were shopping at Office Depot.

“The government and the police see it but they don’t do anything,” said Isaac Massry, founder of the Mexico City-based Discolandia chain, which shuttered about half of its 25 stores in recent years because of sales lost to the black market. “When they do close one down it’s up and running again in two hours.”

Corruption plays a role, with some cops and officials in cahoots with the pirates. But in a nation where nearly half the workforce toils in the underground economy because there aren’t enough legitimate jobs, authorities haven’t the resources or the incentive to bust every small-time operator who is just trying to put food on the table.

Indeed, peddlers are organizing to protect their livelihoods. Wearing T-shirts that read “I’m a merchant, not a delinquent,” about 500 vendors of bootleg merchandise marched in Mexico City recently to protest a change to federal law stiffening penalties for those who produce or sell counterfeit goods.

“I have to support my kids,” said Juana Pineda, a single mother of four who sells stolen music. “If [Mexican President Vicente] Fox wants me to stop selling pirated products, I’ll happily do it on the condition that ... he supports them for me.”

Mexico has made some efforts to crack down. In addition to the recently toughened piracy penalties, legislators are seeking other legal changes to make it easier for police and prosecutors to shutter stands, levy fines and file criminal charges. The government has boosted vigilance at customs to root out covert shipments of blank discs and other materials of the trade.

Law enforcement is seizing record volumes of counterfeit products. From July 2003 through March 2004, Mexican authorities made 129 arrests, seized more than 22 million discs and knocked out equipment capable of cranking out more than 250 million CDs annually, according to the Assn. for the Protection of Intellectual Phonographic Rights, an anti-piracy group whose Spanish abbreviation is APDIF. But such investigations take time and money in a nation where cops are busy handling violent crimes.

“It’s like trying to block out the sun with your finger,” said Roger Hernandez, director general of the Mexican office of APDIF. “It’s not enough.”

Officials in the west-central state of Jalisco have decided to take a different tack. They recently launched a pilot program in the capital city of Guadalajara aimed at helping vendors of bootleg movies and music convert to selling the real thing. The idea was to offer these shadow entrepreneurs the opportunity to buy original product at discount prices, as well as modest loans to finance their inventory.

But so far only about a dozen of nearly 200 targeted vendors have made the switch, and even they are backsliding. Pitching his wares at a street market one recent afternoon, program participant Luis Gomez demonstrated why.

Pulling out two identical-looking, plastic-wrapped DVDs of a performance of British pop star Robbie Williams, Gomez explained that the one on the right was an original that he sells for 180 pesos, or about $16, a couple of dollars less than in music stores thanks to his discount. The one on the left was a bootleg priced at about $6.

“I’d rather sell the originals,” Gomez said with a shrug. “But the customer decides.”

Indeed, the toughest challenge facing Mexico may be changing the behavior of buyers rather than sellers. The industry has run ads featuring popular Mexican singers imploring fans not to buy stolen music. But the message isn’t resonating with Paulina Sanchez.

Sunglasses perched on her head as she browsed the CDs in Gomez’s stand, the fashionable 22-year-old said she couldn’t remember the last time she bought a legitimate record.

“I can buy five fakes for the price of one original,” Sanchez said. “It just doesn’t make sense to pay more.”

Some industry veterans agree. Former music industry executive Sarquiz said the labels had been slow to tailor products suited to the tastes and pocketbooks of consumers in the developing world. He said bootleggers had filled that void, doing special orders, compiling greatest-hits collections and more.

“They deliver incredibly good service,” Sarquiz said.

In fact, bootlegging is so ingrained in the culture that many have simply resigned themselves to the fact. El Tri’s Lora lent his name to the industry’s anti-piracy campaign. But he admits that his band does nothing to stop sales of illegal music -- even outside its own concerts. He said the group’s one attempt to negotiate sidewalk space for legal vendors ended after bootleggers picketed the gig, accusing El Tri’s members of being corporate sell-outs.

Lora said the band’s main source of income has always come from performing about 250 live shows a year, something that even Mexico’s powerful pirates can’t take away.

“The commercial [recording industry] may disappear,” said Lora, whose group recently celebrated 35 years together. “But we’re going to keep rocking.”

*

Times researcher Cecilia Sanchez contributed to this report.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.