Mr. President, Pardon Jack Johnson

Even those Americans who remember the name of Jack Johnson, the first African American to hold the world heavyweight title, often forget that he spent seven years in Europe as a fugitive and that when he returned to the United States in 1920, he was required to serve a year in Leavenworth.

His crime, hard as it may be to imagine today, was that he crossed state lines with a woman -- a white woman -- and prosecutors weren’t about to let him get away with it. Especially after all the trouble he’d already caused and all the rules he’d already broken.

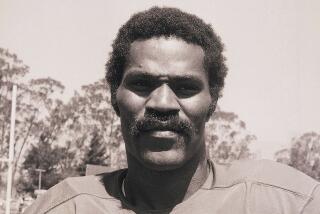

To understand why the U.S. government pursued Johnson for so many years, one must go back to 1908, when Johnson, a 6-foot-1 former dockworker, defeated Tommy Burns and won the world heavyweight title.

His victory shook white Americans hard and prompted a search for a “great white hope” who could win back the title. But repeated attempts were unsuccessful. Two years later, when Johnson defeated the legendary Jim Jeffries, who had come out of retirement and whom most whites considered unbeatable, it sparked deadly race riots across the country.

Johnson was everything that a black man of his era was not supposed to be: outspoken, articulate, intelligent, powerful, wealthy, good-looking and charming. This made him a hero to most of black America, but it also made him a dangerous enemy to much of white America. His mere presence threatened the notion that African Americans belonged to an inferior, subservient race.

Unable to beat him in the ring, his enemies sought other ways to bring Johnson low. In 1912, federal authorities in Chicago went after him in court instead, bringing charges against him for violating the Mann Act, a federal law designed to help fight prostitution by making it a crime to transport a woman across state lines for “immoral purposes.” But virtually everyone knew -- and the prosecuting attorney even admitted -- that the real object was to punish Johnson for daring to engage in romantic relationships with white women.

In court, the federal prosecutors argued that Jackson committed a “crime against nature” for engaging in sexual intercourse with a white woman. The fact that he married the woman only a few months after he was arrested made no difference. He was convicted and sentenced to a year in prison.

After the verdict, the district attorney said that “it was [Johnson’s] misfortune to be the foremost example of the evil in permitting the intermarriage of whites and blacks.”

While his case was on appeal, Johnson fled the country. He lived in Europe as a fugitive from justice for seven years, losing his title in Havana in 1915 to a much younger white opponent after a grueling 26-round fight in 100-degree-plus heat.

He returned to the U.S. in 1920, surrendered to authorities and served a year at Leavenworth.

He never again was given a chance to reclaim the title he had fought so hard to win. Today, his story is known mostly to avid sports fans.

In many ways, Johnson’s adversaries succeeded in their mission to cut him down to size. They sought a conviction against Johnson to send a message to African Americans: Don’t hold your head too high. Don’t believe you’re any better than you really are. Don’t walk too proudly. And never engage in intimate relations with whites.

Today, I am filing a petition with the Department of Justice, prepared by the law firm Proskauer Rose, which documents in detail that the decision to indict Johnson -- and, in the end, the conviction itself -- was racially motivated. The Committee to Pardon Jack Johnson includes prominent Americans from politics, including Sens. John McCain and Edward Kennedy, as well as boxers Vernon Forrest, Sugar Ray Leonard and Bernard Hopkins.

A presidential pardon will not change history. Certainly it will not make life easier for Jack Johnson, who died in 1946. But as McCain has explained, “pardoning Jack Johnson will serve as a historic testament of America’s resolve to live up to its noble ideals of justice and equality.”

*

Ken Burns is a director, producer and writer whose films include “Brooklyn Bridge,” “The Civil War,” “Baseball,” and “Jazz.” His forthcoming film, “Unforgiveable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson,” will be broadcast on PBS in January.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.