Court of Last Resort

Three rows from the basketball court, two men wore orange prison jumpsuits, No. 8 on the front, and Kobe Bryant got it.

That the Lakers were in Denver, that the crowd booed and heckled him only 120 miles from the mountain resort where he had been accused of rape, and from the courthouse where he returned frequently to defend himself against the felony charge, removed the possibility of misunderstanding.

As Bryant walked onto the court, the men raised their beer cups, saluting him from 20 feet away.

He’d seen other signs in other arenas. “Guilty” in Detroit. “No Means No” in San Antonio.

He had heard the chants, the boos, the rush to conclusions. Only 25, he had a charmed life. He was rich. He had won three NBA championships. Yet now he was considered so imperfect -- so vulnerable -- that two men dressed like inmates mocked him.

Bryant met their loopy gazes. Moments before the Lakers would play the Nuggets on a Wednesday late in February, he stared at one man, then the other.

Nine men in uniforms waited behind him, but he lingered a few seconds on the orange jumpsuits. Finally, he clapped his hands twice and ducked his head slightly, chasing away the image.

Next game. Next whatever.

Somewhere between the frivolity of basketball and the gravity of a criminal trial dangles Bryant, going on a year, going on a lifetime.

On June 30 of last year, he left Los Angeles on a private jet, Laker management and medical personnel unaware he was to undergo surgery in Vail, Colo., to fix his swollen knee.

That night, Bryant and a 19-year-old resort employee had an encounter in his room. She says she was raped; he says they had consensual sex.

A Colorado jury will attempt to sort out the truth, but already the encounter has cost him millions in attorneys fees and lost endorsements -- and far more that is incalculable. His meticulously crafted reputation is a shambles. The relationship with his wife, Vanessa, was strained.

And he lost what he long has held dear. Control.

Suspicious by nature, private through nurture, Bryant was nearly always sheltered -- by his parents, the Lakers, and by hired hands wearing sunglasses and hidden microphones. Through it, though, he steered the ship. He alone determined who was allowed on and who was tossed overboard.

It all seemed to work so well. He was a pitchman for mainstream giants Coca-Cola, McDonalds and Nike. He is regarded as one of the best players of his generation, perhaps of all time, precocious, egocentric but undeniably gifted, with a flair for the big play.

Yet despite overcoming distance and discord to repeatedly rescue the Lakers, even at the end of days spent in an Eagle, Colo., courthouse, Bryant’s relentless drumbeat of crease-and-fold life-management, his steady rhythm of stewardship, has vanished.

He must now rely on a battery of high-priced attorneys and, eventually, 12 people he has never met. And it will take more than determination and a couple of hand claps to send the difficult parts away, to bring the old life back.

The Ballplayer

It is again a Wednesday night, now in May and in San Antonio, and the Lakers are struggling in the Western Conference semifinals against the Spurs.

Bryant is in foul trouble, so he sits on the bench, the series slipping toward 0-2. His face is expressionless, his eyes flat, his posture soft, his game inexplicably ordinary.

The Lakers leave the floor at halftime and Bryant shuffles among them. In the stands beside the tunnel, a man rises and holds a sign over his head. Bryant glances up.

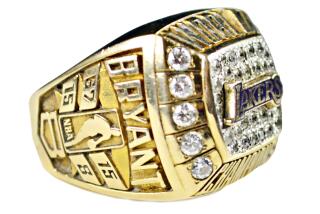

The sign reads, “At Least Kobe’s Wife Got a Ring,” a reference to the $4-million gift he bought Vanessa shortly after the allegation against him became public.

Bryant looks away. It wasn’t a great day.

In the morning newspaper, Laker center Shaquille O’Neal’s father had questioned Bryant’s commitment to the team agenda. Some of his teammates smiled, a few because they were amused by the old man’s temerity, others because he had said what they held inside.

Another critic, another hit absorbed silently. Earlier that evening, Bryant pulled black socks over his feet amid the bustle of the pregame locker room. Reporters on approaching deadlines ignored him, long ago run off by flat answers or surly dispositions.

Still, the Lakers lean on him, like it or not. Their chances of winning an NBA title largely depend on Bryant, and somewhere under their thick layers of ego, his teammates know it.

“To have him make it to this point, among all the trials and traveling, I don’t think any of us could imagine it going as smoothly as it did in terms of his productivity,” Laker forward Rick Fox said.

Indeed, in a season of unparalleled distraction, on a team that listed and sagged under the weight of four superstars, he was first team All-NBA and first team All-Defense. And with the Lakers in danger of again being eliminated by the Spurs, Bryant played splendidly in four consecutive victories.

“The determination he has, I can compare only to a guy like Michael Jordan,” teammate Horace Grant said. “The work ethic, the heart, things like that. I know one thing, he still wants to become the best basketball player in the history of the game.”

Bryant began the season uncertain if he would play basketball at all. He was two days late to training camp in August, and when he arrived he was thin and looked tired. His skin was nearly the color of shale, as though he hadn’t been outdoors in months. His knee had not yet healed.

He was there because he had nothing to hide, he said, and because his young wife had insisted he come. He said he would make the basketball court his personal shelter, and it would protect him from those who would judge him prematurely. He, in turn, would protect his family with all his might.

“When I saw him in Hawaii, it was like seeing a different person,” Grant said. “You could see the wear and tear on him, mentally and physically. You knew deep down inside it was really tearing him up.”

Still, morning after morning, he found his sneakers, found the keys to his Mercedes or his Ducati motorcycle, found just enough desire to play.

In gyms from Honolulu to El Segundo to New York, he stood in body, and maybe in mind. Bryant’s life had split three ways -- at home, with his wife and year-old daughter; in Colorado, facing the sexual assault charge; on the basketball court, with his teammates.

He missed one game and lots of practice time because of court hearings, left his team during a trip to spend a night at home, was awakened in his bedroom by alarms at 4 a.m. so he could catch his chartered jet back to Eagle. But in public the segments of his life remained apart, separated by Bryant’s elusiveness, his ability to compartmentalize -- and directives from the Lakers to reporters not to reference his legal issues, at the risk of revocation of their credentials.

Basketball, a game of five, became his nightly catharsis, a way to play away the shame, the anger, whatever was there that day. Some games, he padded nervously and played with ferocity. In others, his shoulders fell, his eyes went dull, and he had just enough energy to get to work.

Many nights, Bryant remade himself from defendant to All-Star in a few trips down the floor.

He would stand among teammates, staring off somewhere or sharing a private joke, and together they would pretend to ignore the boos or the cheers, depending on the arena. He played the season free on pocket change, a $25,000 bond, the symbolic tether to the Colorado legal system, to The People of The State of Colorado vs. Kobe Bean Bryant, Case No. 03CR204.

He said in Hawaii that he preferred to be at home, with Vanessa and their daughter Natalia. If it ever appeared otherwise, he said, it was because “I don’t have any choice.”

“You can’t imagine what it’s like going through what I’ve gone through, what I’m still going through,” he said. “But I come out here to play, this is my job. I’m going to come out here, I’m going to do it well.”

He was the leading All-Star game vote-getter among Western Conference players. When the Lakers won and Bryant scored, the fans at Staples Center chanted “MVP! MVP!”

But there were issues, and they were obvious.

The Lakers had added Karl Malone and Gary Payton to their lineup, both taking massive pay cuts for the chance to play alongside O’Neal and Bryant, and for Coach Phil Jackson. Malone and Payton were convincingly subordinate to the roles of O’Neal and Bryant, respectful of what had been built.

What they did not expect was to be ignored, to stand open and willing and Hall of Fame credentialed while Bryant played away his demons with one-on-three forays and wild shots.

On Dec. 19, Bryant flew at dawn to Eagle, attended a day-long court hearing, returned to Los Angeles, jogged onto the Staples Center floor before the second quarter, shot without conscience and won the game with a last-second jumper.

Afterward, Bryant reflected on “the irony of it” while teammates groused privately about his offensive gluttony and Jackson observed, “He tried to take some shots that I wouldn’t recommend him to take.”

But it was Bryant who was carried from the floor by a standing ovation, one of several for him that night, though more than one Laker passed without offering so much as a handshake.

Against Orlando in March, one game after he took 25 shots and scored 35 points against the Chicago Bulls, he took three shots and scored one point in the first half. It was as if he was saying, “Try to do it without me.” The Lakers trailed by 11 points.

Yet, after halftime, he was suddenly himself again, erupting for 37 points -- a franchise record-tying 24 in the final quarter -- to spark a victory in overtime.

Then there was his perplexing behavior during a critical game in April against the Sacramento Kings. Having taken 72 shots in the previous three games, Bryant took only one in the game’s first 24 minutes. This time there was no rally at the end. He finished with eight points and the Lakers were crushed.

In the aftermath, Bryant was criticized for an effort that appeared to be either indifferent or by cold calculation. More stinging, an anonymous teammate said, “I don’t know how we can forgive him.”

Bryant stopped talking to reporters for 11 days, but then he had been chilly to the media since early in the season, when his on-again feud with O’Neal brought thick headlines and top-of-the-hour television coverage.

Yet, with all the tumult, and with in-court appearances conflicting with on-court ones, Bryant averaged 27 points after the All-Star break. Further reflecting his uncanny focus, he had a better scoring average and shooting percentage on the road, where he averaged 25.1 points and shot 44.7%, than he did at Staples Center, where fans routinely feted him with standing ovations and he averaged 23 points and shot 43%.

“It seemed as if it was difficult because although he would come and it would be a release, there was still the pressure of his world,” Fox said. “It wasn’t really until he started to feel healthier, physically, when the game came a little easier and it wasn’t a grind to have to be out there, to be the same Kobe Bryant.

“Once he realized that not everybody was going to spend their waking hours booing him and chanting every night, that became better.”

Bryant’s body occasionally failed him. Famously resilient, he missed eight games because of a sprained shoulder, six in January and two in March. He also sat out seven games in late January and early February after slashing his right forefinger in what he said was a household accident.

Asked about holding up through the grind and the hysteria, Bryant said, “I try not to think about it. I try to find the blessing in it, go from there.”

The Accused

On the basketball court, Kobe Bryant’s demeanor is determined, and joyous. He is in constant motion, running, jumping, gesturing.

In Eagle County court, he is equally determined, and grim. He is a study of stillness, seated between attorneys Hal Haddon and Pamela Mackey, hands clasped in front of him, reading testimony on a monitor rather than watching the witnesses.

A trial date is expected to be set May 27, the case having inched along at a pace maddening for an athlete accustomed to determining his fate through his physical ability and mental acuity. Bryant learned the night after the incident that he shouldn’t always rely on his instincts.

He initiated a conversation with two investigators he spotted in the parking lot of the resort and, after waving off his bodyguard as if to indicate he had things under control, consented to speak with them in his hotel room. Bryant’s attorneys are now trying to keep that hour-long, secretly tape-recorded interview out of court.

It wasn’t until after the detectives seized his clothing and sent him to a hospital to produce DNA samples that he finally contacted a lawyer.

Bryant was informed the day after he went home that he had to return to Eagle County to be arrested. The world would know of the allegations.

First, however, he had to tell Vanessa. Just after midnight on July 3, a 911 call was made from Bryant’s house and the Newport Beach Fire Department confirmed that a female was treated at the home at about 1 a.m.

Vanessa accompanied her husband to Eagle on July 4. The rape allegation became public, reporters nationwide flooded the tiny mountain town, and Bryant retreated to the privacy of his multimillion-dollar Newport Coast compound.

His only public comment was a short telephone conversation with The Times eight days after the arrest. “When everything comes clean, it will all be fine, you’ll see,” he said. “But you guys know me, I shouldn’t have to say anything. You know I would never do something like that.”

A single charge of felony sexual assault was filed by Eagle County Dist. Atty. Mark Hurlbert on July 18, and Bryant held a news conference that day at Staples Center, where, with Vanessa at his side, he said through tight lips: “I’m innocent. You know, I didn’t force her to do anything against her will. I’m innocent. You know, I sit here in front of you guys, furious at myself, disgusted at myself for making the mistake of adultery.”

There was a circus atmosphere at his first court appearance, in August, with some 400 media members there, some setting up tents on the lawn and adjoining property. Bryant was greeted by cheers from spectators and curiosity seekers, several with Laker jerseys, painted body parts and crass signs, hoping to get air time.

Bryant has received anonymous death threats -- as have his accuser, the prosecutor and the judge -- but interest by Eagle locals waned months ago. At recent hearings the number of people in attendance besides media and police officers could be counted on one hand.

Four months of proceedings pertaining to the woman’s medical records and sexual history have produced a procession of her former boyfriends, classmates and childhood friends. Most of that testimony has taken place out of public view. Bryant, however, has heard every word, learning far more than he ever anticipated about someone he barely knew.

Observers say he is taking an active role in his defense, asking questions and suggesting strategies during lunch meetings with his attorneys and a battery of investigators at the courthouse or at a nearby condominium.

Other days he prefers solitude, retreating to his private jet at Eagle County Airport and eating alone. The trial looms like threatening weather, foreboding, seemingly inevitable. He faces four years to life in prison or 20 years’ probation if convicted.

A gag order imposed by judge Terry Ruckriegle prohibits Bryant and the attorneys from talking publicly about the case. The Lakers have their own ban, and enforce it aggressively. However, Bryant went into damage-control mode after the allegation that he failed to give maximum effort during the April 11 game against Sacramento, appearing two days later on KLAC radio during the Laker pregame show.

He asked fans to remember how difficult the season has been for him, given his legal situation.

“That’s another one of the reasons why it upsets me so much to hear people say I tanked a game,” he said. “I fly all the way back here, show up for the game. I play hard, play my heart out, play hurt, and then they want to accuse me of tanking a game.”

The Man

Long a basketball star, for a time a polished commercial pitchman with an impeccable public persona, Kobe Bryant is now tabloid fodder. This, as much as the estimated $3 million he has spent so far for his legal team, is the price he must pay.

The ring he bought Vanessa in August, his seeming devil-may-care motorcycle excursions, tales of a woman in Portland who said he made sexual advances toward her, it’s all out there for the consumption of anyone standing in a grocery line.

Bryant on several occasions has said he is afraid, and never more convincingly than during training camp, when he admitted to being “terrified.”

“Not so much for myself, but just for what my family’s been going through,” he said. “They’ve got nothing to do with this. Just because their names have been dragged through the mud, I’m scared for them.

“I feel like I can deal with this. I have to deal with this. But my family, they’re not to blame.”

Not culpable, yet embroiled nonetheless.

Since the alleged rape, Bryant seemingly has tried to renew his commitment to his wife. In addition to the eight-carat diamond ring, he bought identical his-and-hers diamond bracelets. Before training camp, for the first time in his life, he got tattoos. On his right arm are a crown, Vanessa’s name, angel wings and a halo above Psalm 27, a Bible verse that says, in part, “The Lord is my light and my salvation, whom do I fear? The Lord is my life’s refuge, of whom am I afraid?” Inside his left arm is the name of their daughter, Natalia Diamante.

“This is a crown for my queen,” he said of Vanessa. “She’s my angel. She’s a blessing to me, her and Natalia.”

Lately, he injects his faith into his infrequent interviews.

“At some point in your life you go through so much, it’s too much for one person to carry, too much of a burden,” he said on KLAC. “You just have to surrender it to God, give it to him, pray for his strength, pray for his guidance, pray for his wisdom in these tough times.

“When you feel like you can’t carry that weight any more, you put it in God’s hands, and he will carry you all the way, man, all the way.”

Legal experts have said Bryant’s attorneys appear to be building a strong defense. Yet the tumultuous Laker season is proof that unforeseen obstacles can crack what seems like a solid foundation. And Bryant must make an important career decision before his legal fate is determined.

He has said he will opt out of his Laker contract, not because he wants to leave, but because doing so would allow him to renegotiate with the team for seven more years.

He has been tied to the same organization since he was 17, and free agency seems to appeal to Bryant’s curious side. In July, he could become the league’s most attractive free agent since O’Neal came out of Orlando eight years ago -- even with a trial pending and the possibility that he might never play another NBA game.

“You’d have to take that chance,” one of the league’s head coaches said.

Publicly, Bryant has said, “I love being a Laker. I love putting on the golden armor. That’s what I call it -- the golden armor.”

But privately players have said Bryant can’t fathom playing another minute on the same team as O’Neal.

Even that dynamic may be changing, though. Recently, people close to Bryant have said he may be more willing to consider a future with the Lakers.

Team insiders believe owner Jerry Buss suspended contract negotiations for O’Neal and Jackson as protection against future ultimatums brought by Bryant, who called out O’Neal, accusing him of being out of shape and lacking leadership skills, and revealed he held little respect for Jackson off the court.

Buss has not overtly picked a side but has established keeping Bryant a Laker as the priority. Buss thinks of Bryant as family, in November saying, “I felt a lot of pain for him, [how] a father experiences tremendous pain for the problems his son is having.

“My basic feeling is this is where he belongs.”

But for how long?

More court dates are scheduled. There is the hearing later this month, and others will begin June 21, the day after the last possible game of the NBA Finals, Lakers or not. The jet flights to Eagle will continue, so will the media glare.

That golden armor?

It no longer protects him.

More to Read

All things Lakers, all the time.

Get all the Lakers news you need in Dan Woike's weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.