Sudan Rebel Leader Turns From War to Government

RUMBEK, Sudan — When John Garang left Khartoum 22 years ago, he was a fast-rising military officer in the Arab-led Sudanese Army sent to quell a budding insurgency in his southern homeland.

Instead, Garang joined south Sudanese rebels and led them into Africa’s longest civil war, a struggle that has claimed the lives of at least 2 million people and displaced 4 million.

At 60, the former Marxist has outlasted three Arab governments in Khartoum, crushed internal mutinies that threatened his leadership and formed an alliance with the Christian right in the U.S. to pressure Sudan’s Islamist regime to end the war.

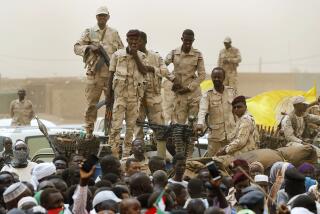

On Friday, the leader of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement made his first visit to Khartoum since 1983 to attend today’s scheduled inauguration of a joint government that will make him president of a semiautonomous southern region and vice president of Africa’s largest country. More than a million people lined the streets of the capital to greet him.

“The struggle has been long and it has been hard,” Garang said during a recent visit to Rumbek, a remote village he uses as his southern base.

Many are hailing Garang’s return to the capital as a triumph. The population there includes many who fled the fighting in the south. But notwithstanding the parade his followers threw for his arrival in Khartoum, Garang’s political battles are just beginning. Some Sudan watchers wonder whether Garang will succeed in helping to bring peace and stability to a nation that has known war for all but 10 years since its independence from Britain in 1956, or whether he will join the long list of leaders who have failed to make the transition from rebel chieftain to statesman.

“It’s simple to destroy,” said Gabriel Mathiang, a former rebel commander who is now speaker of the new southern Sudan People’s Liberation Movement parliament. “It’s harder to build.”

If Garang succeeds, he could help lift 12 million people from extreme poverty in what is regarded as one of Africa’s most backward regions. Despite the 1978 discovery there of some of the continent’s largest oil reserves, the south remains largely devoid of paved roads, electricity, water, hospitals and schools. Because war has made many regions off-limits to doctors and aid workers, diseases that have been controlled in many parts of Africa -- such as polio, malaria, guinea worm and river blindness -- are still rampant in south Sudan.

Garang and his supporters say northern leaders have used Sudan’s newfound oil wealth to buy sophisticated weaponry so they could maintain their comfortable lifestyles and their grip on power. But next week, Garang will sit in a new Cabinet alongside Sudanese strongman Lt. Gen. Omar Hassan Ahmed Bashir, whose regime Garang once described as “the Taliban of Africa.”

“Garang has never trusted anybody from the north,” said Lt. Gen. Lazarus Sumbeiywo, the retired Kenyan army commander who helped mediate the peace deal. “He always thinks they have some trick up their sleeve.”

Garang’s inclusion in the government offers an opening for the restoration of U.S.-Sudanese relations, damaged by Sudan’s sheltering of Osama bin Laden in the 1990s and a recent crackdown in the western Darfur province, where tens of thousands of people have been killed by government-backed militias known as janjaweed. An estimated 2.4 million Darfurians have also fled their homes, many to refugee camps in neighboring Chad. President Bush has described the violence as “genocide.”

U.S. officials expressed hope that Garang’s participation in the national government will help end the crisis in Darfur.

Garang has long offered moral support for the Darfur rebels, and many believe he backed the uprising with guns and ammunition smuggled in from neighboring Eritrea. Garang denies that.

Playing the peacemaker in Darfur would broaden Garang’s political base.

“Garang has evolved into more of an African leader that we can deal with,” said a senior State Department official, speaking on the condition of anonymity. “He’ll never be a one-man, one-vote kind of democrat. And we’ll have to see if he’s matured enough to become a power broker in Khartoum. But if you look at where he was before, he’s come a long way.”

U.S. intelligence officials have been quietly reestablishing links with their counterparts in Sudan as part of Washington’s war on terrorism. In another sign of improving relations, Deputy Secretary of State Robert B. Zoellick will lead a U.S. delegation today at the inauguration.

But the Bush administration has refused to lift economic sanctions imposed against Sudan in the 1990s over the government’s alleged sponsoring of terrorism and repression of the southern population.

Garang’s ties to the United States date to the 1970s, when he graduated from Grinnell College in Iowa, followed by a doctorate in agricultural economics from Iowa State University and a year of military training at Ft. Benning, Ga.

Garang fought briefly against Khartoum in the early days of the civil war, which pitted mostly Arab Muslims in the north against mostly black animists and Christians in the south. The nation enjoyed peace in the 1970s after a peace agreement reached between rebels and the Gaafar Nimeiri regime. But the discovery of oil led Khartoum to break the agreement, and north-south hostilities resumed.

When Garang was ordered to return to the south to quash the uprising, he promptly defected and turned his battalion into one of the first rebel armies.

In the 1980s, he funded his revolt with help from Ethiopia’s Marxist leader, Mengistu Haile Mariam, who received weapons and cash from the Soviet Union. U.S. officials derided Garang as a “Soviet stooge” armed with missiles from Moscow.

By 1991, Garang’s movement was facing a crisis. Some of his own deputies complained about the ruthless tactics he deployed in battles, including stealing or blocking food shipments to the hungry, recruiting child soldiers and attacking aid workers. After his top deputy, Riek Machar, defected that year, the two rebel factions launched fierce attacks against each other for several years, resulting in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people, mostly from disease and starvation.

Also in 1991, Mengistu’s regime collapsed and Garang lost his chief financial backer. Proving his political resourcefulness, Garang turned to the West, emphasizing his movement’s Christian beliefs and playing up Khartoum’s efforts to impose Islamic law on the south.

“His devoutness is directly proportionate to what he thought he could extract from the Christian community,” said Robert Collins, a UC Santa Barbara professor and author of “Civil Wars and Revolution in Sudan.” “He played the Christian card very well.”

Missionaries and U.S. Christian groups, joined by African American congressional leaders, lobbied the Bush administration to engage in Sudan. High-profile figures including Sen. Bill Frist (R-Tenn.) and the Rev. Franklin Graham, son of the Rev. Billy Graham, began calling for humanitarian aid to southern Sudan. Days before Sept. 11, 2001, Bush dispatched former Sen. John C. Danforth as his special envoy to push for peace in the African nation.

Garang started making frequent trips to the U.S., meeting with top administration officials and Christian leaders. The 6-foot-4 militia leader swapped green fatigues for flamboyant African shirts and traded a sidearm for an entourage of cellphone-wielding political aides.

In 2002, peace talks led to a cease-fire, which was followed by an agreement Jan. 9 of this year. Under the deal, Garang will join the Khartoum administration and southerners will receive about one-third of the seats in a new joint government. Oil revenue will be split evenly between the north and south.

At the end of six years, southerners could decide in a referendum whether to break away into a separate country.

Analysts and Garang’s followers agree that maintaining the peace will be more difficult than the battles he has endured since 1983.

“He’s hung in there like grim death over the years,” said Maxwell Gaylard, who spent years in Sudan as chief of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. “But Garang has got real troubles ahead of him.”

He must transform his Sudan People’s Liberation Movement from a fractured, ragtag rebel movement into a democratic civilian government that will satisfy international donors. Under the peace deal, the south stands to receive $2 billion in international aid and $1.5 billion in annual oil revenue. But there is still only one bank in Rumbek, his proposed southern capital, and no investment laws or no official currency.

Rumbek itself is little more than a collection of dirt roads and straw-roofed huts where residents still fetch water from community wells.

On the streets, Garang is widely regarded as a liberator, a Moses-type figure who rescued southern Sudanese from decades of oppression by the north.

“He is always fighting for us,” said Ibrahim Sai Wat, 22, a student who says that thanks to the peace, he has better prospects of finishing his studies. Not long ago, he would have been recruited into the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement.

At Garang’s compound on the edge of town this week, top military and political leaders filed through Garang’s tukal, or grass hut, making final preparations for the trip north and the formal inauguration. Around his camp, scores of excited soldiers piled into trucks headed for Rumbek’s dirt airstrip. Garang brought 1,500 troops to protect him in Khartoum.

Garang can’t afford to take his support in the south for granted, however. Rival southern militias, some of which have been backed by Khartoum, refused to sign the peace agreement and remain a serious threat.

Some southerners have expressed frustration with what they call Garang’s authoritarian style and nepotism. He rewards members of his Dinka tribe with jobs in his administration, according to a survey conducted by National Democratic Institute, a U.S. advocacy group associated with the Democratic Party.

When a top lieutenant openly criticized Garang at a conference late last year, the man received a standing ovation.

Garang is also viewed as out-of-step with other southerners in his long-stated support for keeping Sudan as a unified country, rather than seceding.

“The challenge now for Sudan is to make unity attractive to southern Sudanese so that they vote for it during the referendum,” Garang said during a speech in May marking the anniversary of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement.

Supporters say Garang’s position stems from a desire to one day become president of all of Sudan, not just the south. But most southerners back secession, saying they will never trust the north.

“We are too different. It’s better as two countries,” said Ted Babouth, a movement education administrator and former rebel commander. “At the end of the day, this is a question that may not be up to Garang.”

Analysts say Garang will need to survive the political machinations in Khartoum, where hard-core Islamists view him as an infidel who should not even be allowed into the capital.

Collins, the Sudan scholar, said Arab extremists would be looking for opportunities to sideline Garang.

“The hard-liners in Khartoum are keeping their mouths shut and sharpening their knives,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.