Trial Strategy of Jackson Prosecutor Puzzles Some

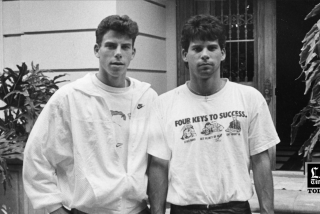

SANTA MARIA — The husky 14-year-old boy who said he watched pop star Michael Jackson molest his older brother was cornered in cross-examination, frustration showing on his boyish face.

He’d testified dishonestly about a seemingly insignificant point, telling jurors that trees blocked the view of a clock tower at Jackson’s Neverland ranch, a point he eventually recanted. It was the second time he had admitted fibbing under oath and one of about a dozen inconsistencies that would be exposed during cross-examination.

“What does it matter?” the boy told Jackson’s defense lawyer, Thomas A. Mesereau Jr. “I don’t know what you’re trying to get at.”

The first days of a trial can burn indelible memories in jurors’ minds. For the eight women and four men deciding the fate of one of the world’s most recognizable celebrities, those first impressions may be of Mesereau grilling the alleged victim’s family.

Santa Barbara County Dist. Atty. Tom Sneddon put the accuser’s brother and sister on the witness stand before calling the alleged victim, a former cancer patient who said Jackson molested him at the singer’s Neverland ranch when he was 13.

But with Jackson’s defense scoring points on cross-examination, some experts question the order in which Sneddon has called the witnesses, noting that the early weak testimony could taint the case.

One former law enforcement officer who knows Sneddon well said the prosecutor is on track. Sneddon is presenting his case chronologically, starting with the airing of a 2003 British TV documentary in which Jackson admitted sleeping with children in a nonsexual manner and moving to the alleged crimes that were the focus of the children’s testimony.

“What he’s trying to do is lay down a story first. Once the story is told, the prosecution has in mind to bring in the corroborating witnesses and the experts to bolster the story,” said former Santa Barbara County Sheriff Jim Thomas, who is analyzing the trial for NBC. “I think the D.A. is feeling pretty good about the case. These are kids. They’re coming across as kids.”

But by the time the alleged victim was called to testify Wednesday afternoon, Mesereau had already cast doubt on the credibility of the boy’s brother and sister, experts say. The defense attorney highlighted the brother’s conflicting accounts of where he was when he saw the molestation, whether he knew where to find a key to Jackson’s wine cellar, and whether there were clocks at Neverland.

“There are discrepancies in the brother’s testimony for which the only logical explanation is he’s lying. That casts a shadow on the credibility of all the family witnesses,” said Denise Gragg, an assistant public defender in Orange County. “If this case relies on his credibility, then the prosecution is going to have a real tough go of it.”

On the stand, the 18-year-old sister sometimes spoke in a little-girl voice.

“That’s my mommy,” she said, identifying her mother in a photo beamed on the courthouse wall.

When the questioning grew hostile, she became unresponsive, explaining that she couldn’t remember things that had happened when she was “just a little kid.” Some of those questions referred to events in 2003, when she was 15.

The siblings’ testimony will probably influence how the jury views the accuser, who is scheduled to begin his third day of testimony Monday.

“If you start out with witnesses who get clobbered, then that impacts on the victim himself,” said Orange County defense lawyer John Barnett, who has represented several high-profile defendants, including one of the officers in the Rodney King police beating trial. “The jury must be thinking, ‘This is just what the defense said the case is about: Lying little teenagers whose parents have groomed them to grift.’

“And that’s where they start their case off. It’s a colossal debacle.”

A better strategy to win over the jury, Barnett and others said, would have been to start with the prosecution witnesses who are less vulnerable on cross-examination.

“Here these people are primed for the trial of the century,” Gragg said. “You want to give them something good to start with. You don’t want to give the defense a chance to look like Perry Mason for a week before you give them something good.”

Whether jurors believe the accusations against Jackson may hinge on whether they are able to look beyond the falsehoods and inconsistencies that have cropped up under tough cross-examination.

And that, in turn, could depend on whether the jury is willing to be flexible with children who say they were beaten by their father more times than they can count.

In court, Jackson’s alleged victim, his older sister and his younger brother all testified that they were frequently assaulted at home, with the sister, now 18, saying the attacks occurred almost daily.

According to prosecutors, that backdrop of domestic violence is crucial to understanding that the children’s testimony about Jackson is essentially true, even if some of the details are not. Jackson’s attorneys, though, say the kids’ anguished past is irrelevant; they contend that the case is nothing more than a chain of lies fabricated to wring money from a vulnerable celebrity.

Some experts on domestic violence see a sad, familiar pattern in the court appearances of the three teenagers.

“There’s a tendency for a lot of child witnesses to minimize acts of abuse,” said Tom Lyon, a USC law professor who specializes in the study of domestic abuse. “A lot of times, children who are molested will say, ‘I was asleep,’ or ‘I decided it was just a dream so I didn’t tell anyone.’ ”

On the witness stand this week, the accuser’s 14-year-old brother was confronted with a deposition he gave at age 10 in his family’s lawsuit against JC Penney. The mother contended she and her children were roughed up and she was sexually assaulted by security guards after being falsely accused of shoplifting.

In his deposition, the boy was asked whether his father ever beat his mother or anyone else in the family. To his embarrassment in court this week, he had answered “never” -- allowing defense attorney Mesereau to cast him as a liar, even at a young age.

But the answer was typical of many abused children, Lyon said: “He was clearly trying to protect someone he loves.”

Also typical, he said, was the brother’s reaction in describing how he saw Jackson allegedly masturbating as he fondled his brother. The boy said he watched only for a few seconds, and then didn’t tell anyone until a psychologist elicited the story months later.

Understandable as that may be, it puts prosecutors in a jam when trying to prove molestation beyond a reasonable doubt.

“The problem,” Lyon said, “is that true accusers don’t look much different than false accusers.”

Prosecutors are expected to present experts on child abuse in an effort to scientifically explain the children’s inconsistencies. Defense attorneys are expected to offer a less complex explanation: The children, they say, are lying.

Thomas, the former sheriff, said Sneddon understands jurors in this part of the state and expects that they will be able to overlook some early missteps by child witnesses.

“You’ve got to give them a break,” Thomas said. “You’re talking about kids versus a polished attorney.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.