A Labor of Tough Love

- Share via

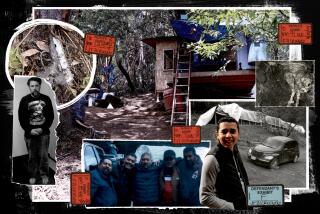

It was hot, but that wasn’t all that was making Michael Wainwright sweat.

“I just pray this goes smooth,” Wainwright said, making his way toward a crowd of boisterous teens gathered outside the sweltering gym at the Nickerson Gardens housing project in Watts.

He was waylaid before he reached the rec center door. “Hey, Wainwright, you got a job for me, right?” shouted a shirtless young man, swaggering over and planting himself in Wainwright’s path.

Wainwright shrugged and sidestepped the youth, clutching two giant piles of documents -- applications, birth certificates, school records -- turned in by Nickerson Garden teenagers who had signed up for summer jobs.

“Did you turn in your documents?” Wainwright shot back. “If I got your documents, you got a job. If you didn’t....”

The boy and his friends began hooting and cussing, mocking the kids filing past them into the gym, where job assignments would be handed out. “If I ain’t got a job, ain’t nobody gon work,” one mumbled.

But Wainwright -- one step ahead of them -- was already engaged in whispered conversation with the self-professed leader of their clique: There might be a couple of unfilled jobs for them, if they settled down.

For four years, Wainwright has been the conduit to work for hundreds of young people in Watts. As head of the Weed and Seed federal anti-crime program there, he trolls Watts’ four housing projects, offering government-funded summer jobs to low-income youths. Always, there are more kids than jobs.

If only that were his biggest problem.

What do you do with a 16-year-old who can’t read well enough to fill out a job application? A 15-year-old whose gang tattoos make him a target outside his housing project? A 14-year-old who needs to work because his mom spent the welfare check on drugs but who missed the deadline to apply because he was locked up in juvenile hall?

How do you function in a place so dangerous that parents go to work with their children on payday so gang-bangers don’t snatch their checks? How do you prepare kids so unfamiliar with convention that their job orientation includes these caveats: “No profanity. You must wear a shirt to work. No rags. No gang banging. No fighting on the job.”

If you’re Wainwright, you set high standards, then bend them. You try tough love, in varying measures of “tough” and “love.” You beg the politicians for more jobs, plead with police for better protection and, sometimes, you side with the weeds you’re supposed to be rooting out.

*

Weed and Seed. It’s a catchy name, a simple concept. Rolled out across the country by the Department of Justice over the last 15 years, the program aims to make neighborhoods safer by helping local police weed out criminals and community agencies bring in services.

In Watts, the weeding process means dislodging gang members from generations-old strongholds and quashing a drug trade that fuels the neighborhood’s underground economy.

The seeding part is not easy either. Often residents are hostile, disillusioned by years of neglect and suspicious of the involvement of the Los Angeles Police Department.

The jobs program -- summer positions for teenagers, internships for young adults, a partnership with Los Angeles Unified that links jobs and classes -- has gone a long way toward easing the tension.

Police say the program has cut summer property crimes by almost one-third in some projects. Wainwright can name dozens of would-be dropouts who returned to school after the program brought teachers into the projects.

But for every youth steered toward productivity, there are others drifting out of reach.

For them the jobs are at best a brief respite from the hostile world of hustling and at worst a dash of cold water on dreams of success and respectability.

Two years ago, 14-year-old Stacey would have been considered a “seed.” Well-mannered, smart and responsible, he spent the summer working in Wainwright’s office: filing, answering phones and earning high marks for his maturity.

But last summer, Stacey didn’t come back. An aunt told Wainwright he was in jail.

Then last month, Stacey showed up at the Weed and Seed office in Watts. “I can’t keep going like this,” he said. “I need a job, man. Bad.”

Wainwright peppered him with questions: Who are you living with? Where’d you get that expensive Sidekick cellphone? Those $300 sneakers in your shopping bag?

Stacey shrugged. “Just hustling, Wainwright. You know how it is.”

Wainwright asked him to empty his pockets. Stacey had almost $300, much of it in $5 and $10 bills.

Most of the jobs had already been taken, Wainwright told him. The best he could promise was yardwork at one of the housing projects.

Stacey shook his head. “Outside? Man, I need an inside job.... You know, a corporate job, with some air-conditioning. If I’m going to work outside, I might as well go back to the corner and make some money.”

He got up and headed for the door. Wainwright held out an arm and stopped him. “Get your documents and come back, man. I’ll see if I can find you something.”

Stacey nodded and eased out. But Wainwright knew he wouldn’t be back.

It would take a week of hauling trash on a Weed and Seed job to make what Stacey could make in one hour peddling rocks of cocaine and bags of weed.

*

It can be a short slide from seed to weed. Wainwright knows. He was a weed himself not too long ago.

He arrived in Los Angeles from Chicago in 1978 with a college degree, a solid resume and a plan to help his older sister launch a business of her own. But he fell for a woman who ran with a rough crowd and wound up using, then selling, drugs.

His downfall was swift and harsh. He spent the next 15 years cycling in and out of jail for “selling drugs, using drugs, cutting people, shooting at people.”

He embarrassed his siblings, disappointed his parents, exhausted the goodwill of his friends. By 2000, Wainwright had landed -- tired, discouraged and pushing 50 -- at the Nickerson Gardens housing project, sharing the apartment of a “lady friend” and passing his days smoking marijuana.

To fill his idle time, he started a reading class for neighborhood children and organized cleanup projects for teenagers. He went to meetings of the resident management council and began badgering community agencies to find jobs for the project’s aimless youths.

One group gave him 50 government-funded slots to fill, but no one expected much. Nickerson Gardens -- the city’s largest and most combustible public housing project -- is considered a no-man’s land, a place where swagger is a stand-in for success.

By summer’s end, Wainwright had put 50 young men and women to work cleaning up the project’s parking lots and yards.

And he had come to realize that his life also needed cleaning up.

“These kids I was passing out [employment] fliers to were the same kids who had seen me sitting out in front of the house smoking a joint,” he says now. “I knew then I had to change my ways.”

The next summer, in 2002, Wainwright hustled for more jobs and got 100 slots, 25 at each of Watts’ four housing projects. He went door to door and filled them all.

That caught the eye of LAPD Cmdr. Terry Hara, then a captain heading the department’s Southeast Division. Responsible for launching Weed and Seed in Watts, Hara had 90 days to fill 450 summer jobs.

“I knew he had the same vision for the community that I did,” Hara said. Hara didn’t have much in the way of salary to offer: $12,000 a year to head the program’s seeding efforts. But “when I asked him to come on board, he jumped.”

The assignment didn’t go over well with officers patrolling the housing projects. Wainwright was pushy, impatient, rough around the edges: a little too much like the project youths he was trying to help.

His bosses overlooked his lack of tact. “Michael is so passionate about getting these kids off the street, keeping them busy, keeping them in school, if he had to, he’d get on his knees and beg,” said Deputy U.S. Atty. Grace Denton, who supervises Los Angeles’ 11 Weed and Seed sites. “That community accepted us because of Michael Wainwright.”

Then a Department of Justice background check spit out two 8-year-old no-bail warrants, charging Wainwright with mayhem and drug trafficking.

Hara called Wainwright in to the office on a Saturday and told him to hand over his keys. Hara could have arrested him on the spot. Instead, he allowed Wainwright to turn himself in.

“I trusted him,” Hara says now. “I was willing to do whatever it would take to allow him to keep doing what he was doing for the community.”

Hara wrote a letter praising Wainwright’s work in Watts, as did Denton, several ministers and social service providers. Wainwright gave a passionate account of his transformation.

The judge was impressed. He recalled the warrants and expunged Wainwright’s record so he could keep his Department of Justice employment clearance.

Wainwright’s past still doesn’t sit well with some cops. “They look at him as an ex-con and a thug,” said LAPD Sgt. Jerome Walker, who shares an office with Wainwright and runs the law enforcement portion of Weed and Seed.

“I look at it differently. I’ve seen this man in tears, trying to get assistance for these kids. Here’s a man who’s made changes in his life. And he’s created over 300 jobs for the kids in this community.”

*

Hara sees Wainwright’s life as rehabilitation writ large, a lesson for young people facing temptations. “I hope they would learn from his problems and not repeat them,” he said. “And see that you can change and turn your life around.”

Wainwright sees himself not as savior but as soldier. “It’s repentance,” he says of his work. “Paying the Lord back for all those drugs I sold, all the food I took out of the mouths of kids.”

He seldom shares his story with strangers but speaks bluntly to young people who ask. “I let them know how stupid and ignorant I was.”

And for all his street sensibilities -- his baseball cap, baggy pants and gold rings -- the values Wainwright promotes are solidly old-school.

He was the youngest of eight children. His father worked seven days a week in a steel mill in Gary, Ind., to keep them all in Catholic schools. His mother rose early each day and made breakfast “cooked to order” for every child. But she was also handy with a belt. A whipping was in order for any child who talked back, brought home bad grades or mistreated a brother or sister.

“We had to say ‘good morning,’ ‘good night’ and ‘I love you,’ every day, to every sibling,” Wainwright recalled, “no matter how we felt.”

Wainwright got his first job at 14, and by 16, he was working in the steel mill weekends and summers. “I remember I made $35 every two weeks, and I had to give my mother $15 of that,” he said. “She wanted me to know what the real world was like.”

He tries to treat the teenagers he encounters with that same mix of tenderness and toughness. On orientation day at Nickerson Gardens, he circled the gym like a frazzled big brother, addressing young women as “little sister” and greeting streetwise boys with shameless hugs.

“This is not the place,” he scolded a group of trash-talking boys. “Stop disrespecting each other.” He put his arm around another boy’s shoulders and tried to steer him away from a knot of young toughs. He ordered a bare-chested young man to cover up. The young man muttered a retort under his breath but pulled on a shirt.

Boys heading for his office hike their pants up in the parking lot. “They know better than to come in here with their jeans sagging around their knees,” he says.

And Wainwright knows better than to pull punches when he sends young men and women out into the world.

You can’t get those corporate jobs you want if you can’t pass a drug test, he warns them. “Everybody knows that for $40, you can buy some stuff that’s supposed to clean [drugs from] your system. I tell them, ‘Forget about that. Just stop smoking weed long enough to pass the test.’

“The ones who are willing to stop for a while -- I can find jobs for them,” he says. The others? “I tell them, ‘If you can’t stop smoking for 30 days, you don’t need a job, you need a [rehab] program.’ ”

Still, Wainwright has been embarrassed more times than he can count. “I’ve had so many employers call me and say, ‘This one didn’t pass the drug test. That one didn’t show up on time.’

“Then they start in with the excuses.... ‘My baby’s mama didn’t wake me up ‘cause, see, I was spending the night at her house and she didn’t have no alarm clock....’ ” He waves his arm in disgust.

“Some of these kids come from families where nobody works. Coming to work on time, listening to authority, taking orders.... We have to start with the preliminaries,” he said.

Yet Wainwright is not afraid to take a chance, to hire a young father just out of jail to supervise teen workers at Weed and Seed. “I write to them [in jail]. I put money on their books. They come see me when they get out.”

He knows the line between weed and seed is fuzzy sometimes.

“Some of them just need second chances,” he said. “Some of them -- they’re not so different from me.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.