‘Idol’? You sing like a donkey

ADDIS ABABA, Ethiopia — “Ethiopian Idols” is a far cry from the glamour and glitz of its U.S. and British inspirations.

Yellowed satin sheets and signs taped to the walls provide the backdrop for a set hastily constructed each week in a shabby hotel restaurant while waiters peer in. Performers have to contend with frequent power cuts, feedback from poor sound equipment and ringing cellphones.

But “Ethiopian Idols” has its own answer to Simon Cowell, the acerbic judge on the American and British versions. Feleke Hailu disses contestants by telling them they “sing like donkeys.”

The show has fast won the highest ratings on otherwise dull state-run TV.

Although “Ethiopian Idols” cannot promise the riches or fame enjoyed by American and British winners, it does offer hope in an impoverished country where most of the 77 million people cannot afford a TV set.

The show also has broken new cultural ground in the Horn of Africa nation.

Feleke’s catch phrase -- “alta fakedem,” or “you didn’t make it” in Amharic -- may seem positively meek compared with Cowell’s biting reviews. But it has caused a sensation in this tradition-bound culture.

“Most of the time I tell [contestants] to go back to their old jobs, forget about a career in singing,” the 46-year-old saxophonist said. “Or I tell them they sing like donkeys.

“Sometimes they get angry. The girls burst into tears, and a few weeks ago one singer threw a stick at me after I told him he had failed to get through to the next round.

“The problem is in our culture. It is not common to tell the truth or criticize. People cannot take criticism.”

Fan Ejigahu Melesse says at first she and her friends were astounded by the bluntness of Feleke and his three fellow judges.

“I couldn’t believe what they were saying to the singers,” said the 25-year-old shop assistant, who lives in the capital, Addis Ababa. “We just don’t do that here in Ethiopia. But gradually we became addicted because it was so refreshing. Now we don’t miss a show and think Feleke’s comments are hilarious.”

Although fans may be captivated, performers have been stung.

The judges “are criminals,” said Natinel Amsalu, a 17-year-old student and amateur crooner who was raked over the coals by the all-male panel after his croaky rendition of “My Love,” a local song made popular by Ethiopian star Theodros Kassahun Kassahun.

“I am a very good singer but the judges kept saying I had serious problems reaching the high notes,” said Natinel, who practices each day in front of a mirror. “They did not even listen to me. What they have done is a very bad thing. They made me look a fool.”

Natinel paid $10 of his hard-earned savings to travel 300 miles from Gonder in northern Ethiopia to Addis Ababa to compete.

Contestants like Natinel are drawn by the prospect of winning a local record deal and an as-yet-undetermined cash prize. The yearlong program, scheduled to end in September, was put together on a budget of $100,000.

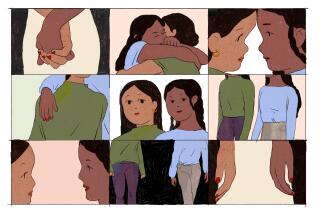

Medina Mohammed, a 17-year-old student who made it through one elimination round after traveling some 180 miles from the Afar region to compete, said her family watches the show in a bar. “We love it,” she said.

“Feleke wasn’t too tough, but his reputation made me nervous,” added Medina, who has tribal scars on her cheeks and performed in the multicolored beads and red cloth of her Afar ethnic group. She sang a traditional love song, “I’m So Glad You Came.”

Judges described her voice as “honey-like,” and her appearance was rebroadcast on a special for Ethiopian Christmas.

Some contestants tackle songs made popular by Whitney Houston and Britney Spears, but most sing local love songs and appear draped in the traditional national dress of white cotton or ethnic costumes.

After the four judges whittle down the original 2,000 contestants to 96, the winner will be decided by the public by a phone-in ballot. This is the first time such polling will be used in Ethiopia.