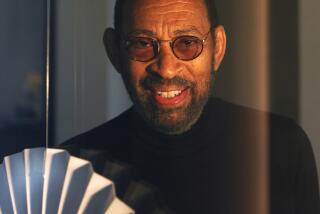

Fayard Nicholas, 91; He Was Elder Half of Tap-Dancing Nicholas Brothers

Fayard Nicholas, the elder half of the show-stopping Nicholas Brothers tap-dancing duo that thrilled audiences during the 1930s and beyond with their elegance and daring athleticism, has died. He was 91.

Nicholas, who had been in failing health since suffering a stroke in November, died of pneumonia Tuesday at his home in Toluca Lake, said Paula Broussard, a friend.

The self-taught Nicholas Brothers -- Fayard and Harold -- tap-danced their way from vaudeville and Harlem’s legendary Cotton Club to Broadway and Hollywood. Known for their airborne splits and acrobatics, the handsome, dapper duo is considered by many to be the greatest dance team ever to work in American movies.

The Russian ballet dancer Mikhail Baryshnikov once called them “the most amazing dancers I have ever seen in my life -- ever.”

When filmgoers saw the Nicholas Brothers’ dazzling acrobatic routine in the 1940 movie musical “Down Argentine Way” (starring Don Ameche, Betty Grable and Carmen Miranda), they were known to applaud and stomp their feet until the projectionist rewound the film and played the dance sequence again.

Fred Astaire considered the Nicholas Brothers’ “Jumpin’ Jive” dance sequence in the 1943, all-black musical “Stormy Weather” the greatest dance number ever filmed.

Miles Kreuger, president of the Los Angeles-based Institute of the American Musical, agrees.

“With its spectacular splits and leaps, their ‘Jumpin’ Jive’ number is easily the most exhilarating dance routine in all of cinema,” he said.

The show-stopping performance, set in a large cabaret with the Cab Calloway band playing, has the brothers jumping onto tabletops and leaping off a grand piano onto the dance floor in full splits.

The highlight of their breathtaking, synchronous routine occurs when they leap over each other in splits while descending an oversized staircase.

“That was one take, coming down those stairs ... jumping over each other’s heads,” Nicholas told The Times in 1989.

“It’s simply unbelievable,” Kreuger said.

Fayard Nicholas was born in Mobile, Ala., in 1914; Harold arrived seven years later. Their musician parents played in vaudeville pit orchestras, and Fayard learned to dance by watching the shows.

“One day at the Standard Theater in Philadelphia,” he told Associated Press in 1999, “I looked onstage and I thought, ‘They’re having fun up there; I’d like to do something like that.’ ”

So he copied what he saw, taught it to his brother and worked up a vaudeville act called the Nicholas Kids.

“We were tap dancers, but we put more style into it, more bodywork, instead of just footwork,” Harold Nicholas said in a 1987 interview.

Fayard, he said in another interview, “was like a poet ... talking to you with his hands and feet.”

In 1932, the two young performers made their film debuts in a short subject (“Pie, Pie Blackbird” with Eubie Blake) and the same year began singing and dancing at the Cotton Club.

They caught the eye of Hollywood producer Samuel Goldwyn, who hired them for their first major film musical, “Kid Millions” featuring Eddie Cantor (1934). “The Big Broadcast of 1936” followed.

The Nicholas Brothers appeared on Broadway in “The Ziegfeld Follies of 1936” and in 1937 they worked with ballet choreographer George Balanchine in the Rodgers and Hart Broadway musical-comedy “Babes in Arms.”

In 1938, the Nicholas Brothers used their engagements at the Cotton Club to refine and update their style, and they took that style back to Hollywood in a series of musical films made throughout the 1940s.

Among those films are “Sun Valley Serenade” (1941), in which they memorably performed the number “Chattanooga Choo-Choo” with Dorothy Dandridge, whom Harold later married and divorced; “Orchestra Wives” (1942) and “The Pirate” (1948), which was highlighted by their acrobatic routine with Gene Kelly in the “Be a Clown” number.

“We call our style of dancing classical tap,” Nicholas said in a 1991 Washington Post interview. “Some people think we’re a flash act. But we’re not. At the end of the act, we’d put those splits in, but we’d do them gracefully. You don’t just hit, bam and jump up. We tried to make it look easy. It’s not easy. But we tried to make it look that way -- come up and smile.”

After spending a year in the Army stateside during World War II, Fayard re-teamed with Harold. In 1946, Fayard had a featured role in the Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer Broadway musical “St. Louis Woman,” in which Harold had the lead. They then embarked on a series of international tours.

In 1948, they gave a royal command performance for the king of England at the London Palladium. Later, they danced for nine U.S. presidents.

Nightclubs, tours and television appearances dominated their performing schedule for the next decade, along with a number of projects away from each other.

With Harold working in Europe and Fayard in the United States, the Nicholas Brothers did not perform as a team for seven years.

The brothers reunited as a duo in 1964 for an appearance on “The Hollywood Palace” TV variety show.

But they lived on opposite coasts after that, Broussard said, and when not performing together they performed separately.

On his own, Fayard Nicholas took on a dramatic role in the 1970 movie “The Liberation of L.B. Jones” and won a Tony for his choreography for the Broadway revue “Black and Blue” (1989), which included a dance on stairs for three child tap dancers, one of whom was a young Savion Glover.

Among a string of awards in their later years, the Nicholas Brothers in 1991 received Kennedy Center Honors and were honored at the Academy Awards.

Broussard, who had been working with Fayard on a biography of the Nicholas Brothers in recent years, said he remained active after his brother’s death in 2000, dancing at tap festivals and giving lecture-demonstrations -- after having had both hips replaced due to arthritis.

“He was the consummate entertainer and just one of the nicest people I’ve ever met,” Broussard said. “He just always had a big smile on his face.”

Fayard Nicholas’ dance choreography and the brothers’ place in dance history were chronicled in the 2000 book “Brotherhood in Rhythm” by Constance Valis Hill.

The Nicholas Brothers also were the subject of a television documentary, “The Nicholas Brothers: We Sing and We Dance” (1992).

The late tap dancer Gregory Hines said in the foreword to “Brotherhood in Rhythm” that if Hollywood were to make a movie of the Nicholas Brothers’ lives, “the dance numbers would have to be computer-generated.”

Nicholas is survived by his third wife, Katherine Hopkins-Nicholas; his sister, Dorothy Nicholas Morrow; his sons, Tony and Paul; four grandchildren; and a great-granddaughter.

Services are pending.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.