On opposite coasts, two political stars are rising

ALBANY, N.Y. — They appear to have little in common, these two governors.

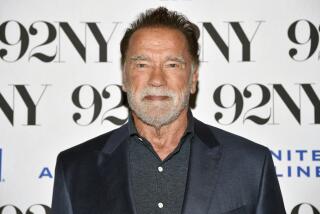

One is a pumped-up, Harley-riding movie star with a taste for Hummers, Armani suits and the Kennedy clan. The other is a rail-thin wonk with a perfect LSAT score who is far more comfortable jousting over budgets than making small talk.

One threw a $2.4-million party to celebrate his most recent electoral victory, an event televised nationally and paid for by big business. The other marked his win with an austere public meet-and-greet as corporate lobbyists fretted that his election would diminish their clout.

One is a Republican, the other a Democrat.

But Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger and New York Gov. Eliot Spitzer share more than an Austrian lineage. (Spitzer’s grandparents were from the old country.) Both have an appetite for big issues and big challenges. And both hope to leverage landslide victories in November -- and the public’s affinity for their ambition -- to transform the role of state government in public life.

And as they barrel ahead on issues that Washington can’t or won’t address -- global warming, universal healthcare, stem cell research -- both are prodding balky Legislatures to act.

“I don’t think we are moving with any greater speed than is called for by the circumstances,” Spitzer told a gaggle of reporters in Brooklyn, a couple of whom questioned whether he understood that the deliberative process involves, well, deliberating with lawmakers.

Spitzer has stepped into a national spotlight on state governance that until recently was directed almost entirely at Schwarzenegger. Like California’s governor, he came into office with a larger-than-life profile, having gained glory as the hard-charging state attorney general who took on Wall Street.

Before bumping into each other at a White House reception last week during a national governors conference, the two had talked only once, in a brief phone conversation in January.

“It was after he hurt himself,” Spitzer said in an interview in his Manhattan field office. “I told him I was ready to take him on the slopes.”

At the White House event, they chatted about the potential for launching policy initiatives together. A spokesman for Schwarzenegger said they agreed that doing so “could be good for the country.” They made plans to talk again soon.

“New York is an extremely important state. California is an extremely important state,” Schwarzenegger said in a recent telephone interview. “If we can form a partnership from the East to the West, that will rub off on other states.”

Spitzer, for his part, says there is much to learn by looking west -- especially in these early days of his administration, when it’s easy to overplay the hand dealt by a big win at the polls.

Spitzer is already at loggerheads with legislators bent on bringing him down to size. And he doesn’t pull punches himself, calling the New York Legislature -- rated in one academic study as the most dysfunctional in the country -- an institution regarded as “slow, loath to make tough decisions, hidebound, overrun by lobbyists and which has taken the state in a direction that hasn’t been terribly productive.”

It wasn’t long ago that Schwarzenegger was similarly frustrated.

“I’ve watched what happened in California,” Spitzer said. “Gov. Schwarzenegger came in and tried some things. They didn’t work necessarily. He redirected the ship, and he seems to be doing stupendously now. There are many lessons you can take from it.”

Spitzer’s agenda is ambitious and in some ways familiar to Californians: provide healthcare to uninsured children and adults, fund stem cell research, invest big in infrastructure, overhaul the way state aid to schools is doled out and restructure the property tax system.

Forgive him, he says, if he is in a rush. Like Schwarzenegger, he is fed up with the federal government. So Spitzer is doing what he did as an attorney general: finding ways to use untapped powers entrusted to the state.

“The whole country knows we are going through a time of stalemate and dysfunctionality in Washington,” said David Gergen, who was a senior advisor to former Presidents Reagan and Clinton. “When the economy is working well but the federal government can’t get anything done, there is room for creative governors to step up. Both are doing so boldly.”

Before moving into the governor’s mansion, Spitzer was hailed as perhaps the most effective state attorney general ever. Time magazine tagged him “Crusader of the Year.” He famously exposed Wall Street firms that were systematically skewing their stock market analyses to benefit big corporate clients.

As governor, he has to work with naysayers in the Legislature. He can’t just haul them into court.

Schwarzenegger’s advice to the New York governor: Try not to lose your cool.

Schwarzenegger confessed squandering a chunk of his first term. “I was too anxious to get things done,” he said. “I had the attitude: ‘Don’t do it my way and I will go to the people.’ I didn’t include the legislators. That was obviously the wrong approach.”

Schwarzenegger is still going his own way in many respects. He recently unveiled a plan to require every Californian to have health insurance.

The proposal, which includes a new payroll tax on thousands of businesses and takes a share of doctors’ and hospitals’ earnings, has angered Schwarzenegger’s fellow Republicans and many of his business supporters. Months earlier, he took his own path by endorsing Democratic lawmakers’ efforts to curb greenhouse gas emissions.

“When you look around the nation and say, where has there been creativity, California and Schwarzenegger immediately come to mind,” Spitzer said, “both in terms of environmental efforts and recently in terms of healthcare. He has certainly been willing to say: ‘What works? How do we do it? Give it a shot and if doesn’t work, try something else.’ ”

“It is not so much a dedication to pure ideology as it is to getting results and testing different concepts. That is what we will be doing as well,” he said.

Spitzer is starting with a healthcare plan about which a key group of his natural allies -- labor -- is less than thrilled. His proposal would redistribute the way billions of Medicaid dollars are allocated, delivering a financial hit to scores of hospitals and other medical institutions. One result could be heavy job losses for the healthcare workers union, one of Albany’s most influential special interests.

Spitzer is unapologetic.

“Until you’ve said ‘no,’ you haven’t really figured out how to govern effectively,” he said. “We are saying ‘no’ to people who are used to hearing ‘yes.’ ”

Not everyone in Albany is going along willingly.

In a heated phone exchange with the Assembly Republican leader, reported by the New York Post, Spitzer referred to himself as a “steamroller” -- punctuating the point with an expletive -- and warning the lawmaker to stay out of his way. The dust-up was reminiscent of Schwarzenegger’s calling California lawmakers “girlie men.” It wasn’t long afterward that Schwarzenegger’s momentum faltered, and his standing with the public sagged.

The day after Spitzer released his proposed budget last month, New York Senate leader Joseph Bruno, a Republican with 30 years in the Legislature, shared a story about attempting to flatten fields on his farm with a steamroller. He got to the bottom of an incline, he said at a news conference, and the machine got stuck.

“Guess what? When the going starts to get a little bit tough, a steamroller spins, it doesn’t advance,” he said. “Negotiation is a fine art. When governing, it is all about compromise. People who draw lines in the sand don’t get on-time budgets. They don’t get results.”

Spitzer’s relationship with legislators is complicated by his anticorruption zeal.

He took the reins in Albany after 10 lawmakers had been indicted or convicted of criminal charges in recent years. The state comptroller recently resigned amid a scandal involving abuse of the perks of office. And Bruno’s business dealings are under investigation by the FBI. The senator has denied any wrongdoing.

Spitzer and Schwarzenegger part ways in the area of campaign finance reform. Schwarzenegger never delivered on promises to get money out of California politics. Rather, he has raised $114 million -- a gubernatorial record -- from special interests.

Spitzer says he is preparing to propose public financing of campaigns and does not accept contributions of more than $10,000. New York law permits donations of five times that amount.

“He came in as Mr. Clean, and the Legislature [is] the thing that needs cleaning,” said former New York Gov. Mario Cuomo. “It puts him in a very strong position.”

A few days after Bruno’s news conference, however, the Democrats who control the Assembly broke a deal they made with Spitzer to select a replacement state comptroller from a group of candidates suggested by an outside panel. They chose a fellow assemblyman who was not recommended by the panel, a move the governor called a triumph of cronyism.

The New York media had already declared Spitzer’s honeymoon over.

“I went on a seven-day honeymoon when I was married,” he said. “Four weeks is not bad from my perspective.”

*

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

Steamroller, meet the Terminator

Gov. Eliot Spitzer

* Grandfather was Austrian

* Faces a Legislature that one study called the most dysfunctional in the country

* Must work with a state Senate leader under investigation by the FBI

* Heir to a multimillion-dollar real estate fortune

* Became famous in his role as “sheriff” of Wall Street

* Elected with 68% of the vote

* Warned a New York lawmaker that he’s a “steamroller” -- punctuated with an expletive

--

Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger

* Emigrated from Austria

* Took office when fewer than 1 in 3 Californians had confidence in the government to do right

* Must work with a state Senate leader under investigation by the FBI

* Made millions in

Hollywood

* Became famous for his roles in “The Terminator” and other films

* Reelected with 56% of the vote

* Called California lawmakers “girlie men”

Source: Times reporting

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.