THE ERAS OF THEIR WAYS

A perfect season. Four championships in the space of seven years.

If the New England Patriots defeat the New York Giants in Super Bowl XLII next Sunday, they will arguably become the gold standard for professional football.

History will place them among modern dynasties in Green Bay and Pittsburgh, Dallas and San Francisco. They will continue to draw comparisons to the undefeated 1972 Miami Dolphins.

But any effort to measure the Patriots against such a far-reaching timeline ignores that football has always been an evolving game. Go back to the advent of the forward pass and modern helmets -- the changes of the last 30 years have been no less significant.

“It’s like going from kindergarten to being a graduate student at MIT,” said Gil Brandt, the former Dallas Cowboys personnel executive. “It’s a huge difference.”

That difference starts with the men playing the game. Don Shula, who coached the Dolphins to their perfect season, says “obviously the players are bigger, faster, stronger.”

In Shula’s days, players often went home at season’s end, taking jobs at car dealerships and insurance agencies. Months passed before they returned to training camp to get back in shape.

“When I coached the Dolphins, we had a Universal gym,” he said. “That was our weight room.”

Today’s players train year-round in elaborate team complexes staffed by nutritionists. The effect is measurable: The 1972 Dolphins offensive line averaged 255 pounds; this season’s New England line weighs in at 306 pounds.

“The biggest difference is off-season conditioning,” Shula said.

And with more time devoted to studying the game, those larger, quicker athletes are plugged into multifaceted West Coast offenses, spread formations and other pass-oriented attacks.

Consider that in Super Bowl VII, Dolphins quarterback Bob Griese threw only 11 times in a 14-7 victory over the Washington Redskins. Patriots quarterback Tom Brady attempted that many passes in the first quarter against San Diego last week.

“I can’t believe all the things that teams are doing,” said Brandt, who now works for NFL.com. “New England runs about five different offenses.”

The other highly visible change has been free agency, which came into the league in 1993, affecting the game in two ways.

Given the proper determination and cash reserves, franchises have the opportunity to assemble a winning team overnight. They can lose top players just as quickly.

“You can build a dynasty, but you can’t keep it,” said Ron Wolf, the former Green Bay Packers general manager. “You’ve got 17 or 18 players changing on your roster every year. It’s more or less like collegiate football with a graduating class that leaves.”

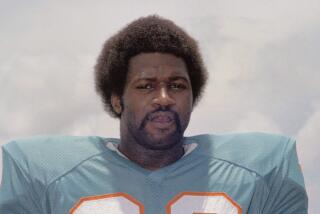

The Dolphins painstakingly assembled an all-star lineup with Griese at quarterback, Larry Csonka, Jim Kiick and Mercury Morris at running back, and Paul Warfield at receiver. Nick Buoniconti, Jake Scott and Dick Anderson led the defense.

Under the rules of that era, Miami did not have to worry about other teams poaching from its lineup. But, as Shula points out, when Csonka, Kiick and Warfield defected to the World Football League in 1975, “I couldn’t go out and get three players to replace them.”

If nothing else, the Patriots have impressed football people with their ability to adjust from one season to the next.

Wolf says the NFL went through a learning experience with free agency. Early on, some franchises spent freely but mortgaged their futures by running smack into the salary cap.

Now he sees New England as a model for dealing with the new economics, spending judiciously and making all the right decisions when it comes to letting players go and finding able replacements.

“That’s what makes the game so fascinating to me right now,” Wolf said. “You look at all the time and effort put into building and maintaining a franchise.”

This season, the Patriots fueled their winning streak by trading for receivers Randy Moss and Wes Welker in the spring, giving Brady two of the most dangerous targets in the league.

But not all of the changes in pro football are so clearly visible, said Sam Wyche, who coached the Cincinnati Bengals to the Super Bowl in 1989.

The game has experienced a technological revolution that has altered scouting and play calling. “It’s subtle, behind the scenes,” Wyche said. “It starts in a personnel office somewhere.”

Whereas franchises used to fit different types of athletes into one style of play, they now have the information to search for players who already fit their offensive or defensive schemes.

Shula recalls that when he started coaching, teams drew up scouting reports on yellow legal pads. Then came the era of the projector and the arduous task of cutting game film into different snippets for offense and defense.

Now, coaches and players call upon databases and digital videotape.

With a few keystrokes, an assistant can calculate how often the other team has run or passed out of a particular formation. A defensive lineman can watch every third-and-two situation his opponent faced the last three seasons.

Teams need larger coaching staffs just to handle the information explosion.

“In 1960, when we started with the Cowboys, we had a head coach and three assistants,” Brandt said. “This season Denver has 19 coaches.”

Yet, for all these changes, people in and around the game say one thing has remained constant: The best and fastest way to the Super Bowl is a talented quarterback.

The value of the position has grown along with the demands of the game, the intricate offenses and coaches sending in plays through a radio receiver in the quarterback’s helmet.

“He’s got to be smart,” Wyche said. “He’s got to get the information, assemble all that, make the call in the huddle and make sure everybody’s got the right look in their eyes. And when he gets to the line of scrimmage, he has to confirm the play or change to something better.”

Miami had Griese, and now the Patriots have Brady. Which circles back to the original question of comparing the teams.

Some former Dolphins players have been quoted as saying they couldn’t match up with the larger, faster Patriots. But Shula believes it’s like comparing apples to oranges.

“If the ’72 Dolphins were playing now, under the same set of rules and circumstances, they would be right there competing with the top teams of today,” the former coach said. “And if the Patriots had to play back in ‘72, this would still be a great football team.”

--

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

Dominating performances

Comparing the current

New England Patriots with

the 1972 Miami Dolphins, who finished with a 17-0 record. These statistics are for scoring offense and defense:

PATRIOTS’ OFFENSE WAS ...

69.6%

... better than average 2007 team

NFL average per game...21.7

Patriots...36.8

PATRIOTS’ DEFENSE WAS ...

21.2%

... better than average 2007 team

NFL average per game...21.7

Patriots...17.1

DOLPHINS’ OFFENSE WAS ...

35.5%

... better than average 1972 team

NFL average per game...20.3

Dolphins...27.5

DOLPHINS’ DEFENSE WAS ...

39.9%

... better than average 1972 team

NFL average per game...20.3

Dolphins...12.2

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.