When the call comes in the middle years

HUNTINGTON, N.Y. — For Robert Holz, the question always lingered.

He’d worked as an accountant for nearly two decades. He was basically happy. He was 40 years old.

Still, the question was there.

“Is God calling me? Or not?” he said.

Partly because he felt unfulfilled, partly in hopes of resolving that nagging question, Holz quit his job and inquired about becoming a priest. He has spent much of the last five years within the yellow brick walls of the Seminary of the Immaculate Conception, a sprawling estate on Long Island Sound where peaceful days are marked by tolling bells.

“The idea of the future is a lot bigger now,” said Holz, now 47 and in his final seminary year.

“You come into the seminary and suddenly you really start looking at eternity. As opposed to when I was younger: Is there enough in the IRAs to retire? What if this, what if that, is my house paid for?”

Holz is among a vanguard of older priests-in-training who are energizing an institution that has faced stiff recruitment challenges for decades.

He’s one of nine men expected to be ordained this June, in what church officials say is among the largest classes of incoming priests in the nation. At its low nine years ago, the Rockville Centre Diocese ordained one priest.

Bishop William Murphy declared the priesthood a priority when he came to Long Island in 2001, and now the number of Rockville Centre seminarians, once in the single digits, is up to 31. More than a third of those studying to be priests on Long Island are older, like Holz.

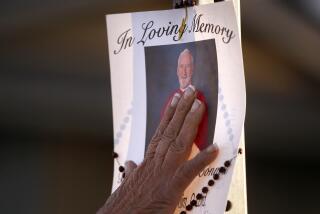

The Sept. 11 attacks helped to inspire some of these men to enter the priesthood; for others, the balance swung after an illness or the loss of a parent. Many said they considered the priesthood as young children but were distracted, uncertain or afraid.

“I was doing well; the companies I worked for were generous, so there were regular promotions, regular raises. But by the end, when I was earning this much more than when I started, I would have expected to be this much happier, and I wasn’t,” said Holz. “Looking for fulfillment is what brought me here.”

For the last decade, the median age for priests at ordination has hovered around 38; in the 1960s, it was 26.

Father Paul Sullins, a professor of sociology at Catholic University of America in Washington, said the trend is probably driven by modern priests’ additional years of education -- they generally finish seminary with a master of divinity degree, rather than a bachelor of divinity -- and the fact that people in general increasingly wait longer before settling on a single path.

New priests of any age are sorely needed. As the number of Catholics in the United States has risen, the number of priests has steadily dropped. According to the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, there are nearly 29,000 priests, about 20% fewer than 40 years ago.

But the worst is probably still ahead. The decline in the number of ordinations nationwide -- 475 in 2007, compared with 994 in 1965 -- and the aging of the current population of priests, whose median age is in the 50s, indicate that the priest shortage will grow more critical.

The decline in priests has led some within the Catholic Church to call for allowing women to be ordained or lifting the vow of celibacy.

While marriage and family are among the life possibilities sacrificed by younger men entering the seminary, it’s different for many of the older men. They said their biggest challenge was the loss of control over their own lives.

Seminarians are allowed freedom to come and go, and communicate with the outside world, but only to a point, said Msgr. James McDonald, rector of the Seminary of the Immaculate Conception.

Much of their day consists of reflection, prayer and study, punctuated by a midday Mass during which only male voices rise in song.

They may have their own bedrooms and bathrooms, but the dormitory-style setting would be familiar to a recent college graduate.

Seminarians at Immaculate Conception -- whose median age is around 34 -- come from career backgrounds as varied as farming, teaching, marketing and sales.

And in addition to work training and life experience, second-career priests said they understood the pressures of the secular world in ways that younger men might not.

Holz explained:

“I know what it feels like when your utilities go up by X percent and your salary goes up by less -- a lot of the things that aren’t necessarily spiritual questions originally, but become them very quickly when people start wondering, ‘Is this what my life is about?’ ”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.