High-tech surveillance greets hockey fans

KENNEWICK, WASH. — The modest junior hockey arena in this small eastern Washington agricultural hub is an ideal gathering place for local families.

It’s also a crucial front in the Department of Homeland Security’s war against suicide bombers.

During the tests of crowd surveillance technology, an array of surveillance cameras, infrared cameras, and millimeter-wave radar is used to scan fans of the Western Hockey League’s Tri-City Americans, who play at the town’s 6,000-seat Toyota Center.

Software algorithms -- complex image-processing formulas called video analytics -- instantly analyze the data and images.

Privacy advocates and critics of Homeland Security spending object to the idea of training all that high technology on law-abiding citizens. But hockey fans in this languid Columbia River town near Oregon don’t seem to mind being test subjects.

“We’re trying to figure out how to protect large venues from terrorist attacks,” said Nicholas Lombardo, project manager for Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, one of nine Department of Energy national laboratories. The lab, in nearby Richland, is coordinating the testing, which initially focuses on pedestrians and will expand to include vehicles in coming years.

In general, the security technology is looking for three things: suicide bombers on foot, suspicious packages left behind and vehicles that may carry explosives. The goal is to identify assailants long before they reach fixed points, like box office windows or bag-search areas.

By pushing detection to 500 feet earlier than traditional checkpoints, the system is able to start tracking people approaching the building from a distance.

Another goal is to inspect every person in a crowd of thousands -- probing for heat generated by concealed explosives, scanning for weapons and analyzing odd behavior.

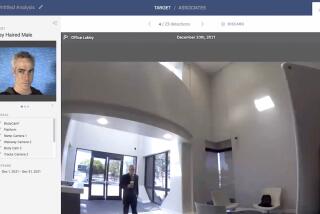

Video streams of crowd movements are fed into computers. If the program detects someone running away from the event or loitering or leaving a package behind, the behavior is highlighted for an operator.

The operators at the Kennewick arena are local law enforcement officers hired to run the equipment from inside a nearby trailer. Watching a wall of flat screens, they can focus all of the different types of cameras on a single person, then decide whether to stop and interrogate the person.

Lombardo hired mock suicide bombers to mix with hockey fans and sneak simulated explosives to the building. Early tests detected some small devices, but Lombardo declined to discuss specific results. Tests also netted two hockey fans, one for carrying a concealed beer can, another for wearing something suspicious that turned out to be a cast.

Potential customers for the new security system include the Transportation Security Administration, the Secret Service and the Department of Defense. The military deploys some similar technologies in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Most of the methods are already commercially available, but they have “not been fused together before,” said James Tuttle, Homeland Security director of explosives for the science and technology directorate.

But Kennewick and Richland, which along with Pasco make up what is known as the Tri-Cities, is near the huge Hanford Site, formerly the Hanford Nuclear Reservation, which was established in 1943 as part of the Manhattan Project. That background entered into the decision to allow the tests, said Jeff Kossow, the Toyota Center’s executive director.

“Because of what’s happened in our history, people here are more accustomed to higher levels of security,” he said.

Notices about the tests are posted in many places around the arena, though it’s hard to miss the roof-mounted cameras or the tripod-based infrared and wave radar devices. Patrons can enter a rear door if they object to being scanned.

Michelle McGuire is president of the Tri-City Hockey Booster Club.

Players in the team’s league are age 16 to 20, and the National Hockey League drafts out of it. Fans have not objected to being spied upon, McGuire said.

“No complaints,” she said. “I don’t have a problem with it.”

Although hometown hockey moms don’t object, privacy advocates cringe.

“This is a silly waste of money,” said Barry Steinhardt, director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s technology and liberty program. “It’s about turning the entire population into a suspect class. Everybody is a suspect.”

Steinhardt criticized Homeland Security for field-testing “exotic technologies” that often produce many false positives, divert security resources, and result in interrogations and searches based on the thin evidence.

Mass surveillance systems don’t work, said Simon Davies, director of Privacy International, a London-based advocacy group that focuses on surveillance and privacy issues raised by governments and corporations.

“Some of the technology being tested is of questionable value, and some constitute an outrageous invasion of privacy,” Davies said in an e-mail interview.

“The millimeter-wave radar is a fancy name for a device that electronically removes your underwear.”

Lombardo adamantly denies that. The images his equipment captures reveal “no modesty concerns,” he said.

--

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.