Preston Gomez helped Angels’ Jose Arredondo solve control issues

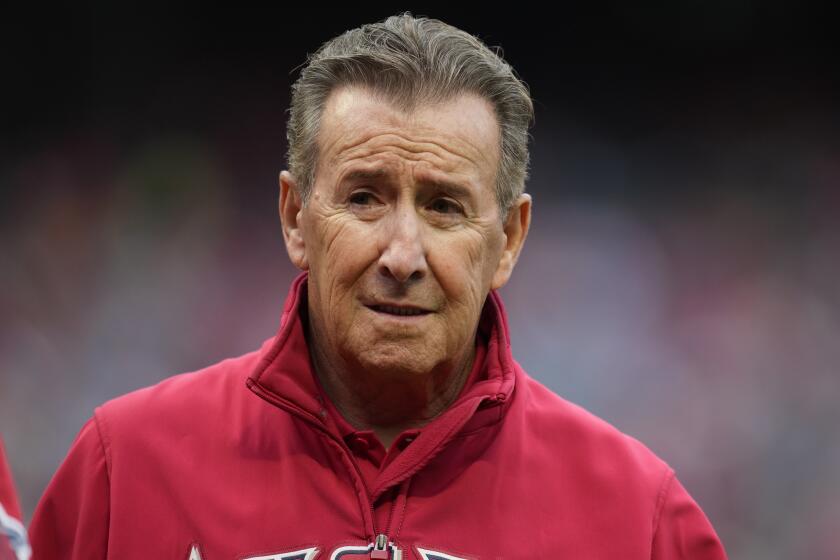

TEMPE, ARIZ. — The Angels this season will wear black diamond-shaped patches, inscribed with the name “Preston,” on the right sleeves of their jerseys in honor of Preston Gomez, the team’s beloved advisor, scout and coach who died in January at 86.

If it were up to Jose Arredondo, the hard-throwing 24-year-old reliever who had a breakthrough 2008 season for the Angels, the patch would be sewn over his heart.

“I love that guy,” Arredondo said, his soft voice barely audible amid the bustle of the team’s spring-training clubhouse. “He taught me everything.”

If Arredondo continues to dominate like he did as a rookie, when he went 10-2 with a 1.62 earned-run average and baffled hitters with a 95-mph fastball and a nasty split-fingered pitch, he will be Gomez’s parting gift to a franchise he served for 28 years.

Arredondo was a self-described “troublemaker” as he came up through the minor leagues, a prospect whose arm was clearly major league-caliber but whose temper threatened to derail him.

In June 2007, at double-A Arkansas, Arredondo threw a tantrum when he was pulled from a game and got into an altercation with veteran outfielder Curtis Pride, who was trying to calm Arredondo in the clubhouse afterward.

The Angels suspended Arredondo for a week and demoted him to Class-A Rancho Cucamonga, where he brooded his way to a 2-4 record and 6.43 ERA in 28 games.

Arredondo had also been at Rancho Cucamonga in 2006 when he and catcher Michael Collins got crossed up, the right-hander firing a fastball when Collins expected a changeup. They then argued and fought in the dugout.

A few days into spring training last February, Manager Mike Scioscia summoned Arredondo, who grew up in the Dominican Republic, to his office for a meeting with pitching coach Mike Butcher and Gomez, a native of Cuba who had a special knack for mentoring Latin players.

The conversation went on for hours, with Scioscia and Butcher, speaking in English, stressing the importance of being professional, of taking his job seriously, of being a good teammate.

But the most pointed words were delivered by Gomez in Spanish.

“He dropped the hammer on him,” Butcher said.

“Preston hit him right between the eyes,” General Manager Tony Reagins said. “. . . He made sure he was accountable for everything, on the field and off.”

Gomez spoke with Arredondo repeatedly that spring “about my discipline and controlling my temper -- he told me how things work in the big leagues,” Arredondo said. “He was all over me, trying to make me better.”

In late March, on the drive from Arizona to Southern California, Gomez stopped at a gas station in Blythe, Calif., and accidentally walked into the path of a pickup truck pulling up to the pumps.

Gomez suffered severe head and internal injuries, and spent much of the next nine months in hospitals and rehabilitation centers. He never really recovered and died on Jan. 13.

In Arredondo, the Angels have tangible evidence of Gomez’s legacy.

After going 1-1 with a 2.12 ERA and 10 saves in 15 games at triple-A Salt Lake, Arredondo was called up on May 14 and gave up a home run to the first batter he faced, Nick Swisher.

But Arredondo did not allow a run over his next 12 innings and quickly emerged as the team’s No. 3 reliever behind closer Francisco Rodriguez and setup man Scot Shields.

Arredondo held opponents to a .190 average, giving up 42 hits, striking out 55 and walking 22 in 61 innings, and his 11 earned runs allowed were the fewest in franchise history by a rookie reliever.

Also significant: He never caused a problem or had a dispute with a teammate or coach.

“I don’t know if I’ve ever seen as dramatic a result from a meeting as Preston’s was with Jose,” Scioscia said. “That was probably the biggest contributor to this kid’s breakthrough and understanding the talent he had and what was at stake if he didn’t apply himself like he needed to.

“I think Jose has a lot of respect for what Preston did for him, and we want to keep that mind-set embedded in Jose.”

Arredondo, married and the father of a 7-year-old girl and 4-year-old boy, said he feels “smarter now, more confident, more relaxed. I used to be angry. Now, I’m a happier person.”

Bobby Magallanes, the Angels’ double-A manager, said the difference is “like night and day” from 2007, when “it was almost like he had a chip on his shoulder, like people were after him.”

Magallanes made the pitching change that sparked Arredondo’s meltdown at Arkansas in 2007.

“He met me by the first-base line, flipped me the ball, and his body language was poor,” Magallanes said. “He threw his hands up. He really let his emotions get the best of him.”

To compound matters, Arredondo then got into a fight with one of the nicest players in recent baseball history. Pride tried to counsel Arredondo, telling him he shouldn’t show up his manager like that, and Arredondo responded with clenched fists.

“Sometimes you get out of control for five seconds,” Arredondo said, “and that’s when you make a mistake.”

With guidance from Gomez, Scioscia and Butcher, Arredondo now channels that anger toward opposing batters.

“I wouldn’t want to face him,” Angels center fielder Torii Hunter said. “He throws 95 mph, then you tick him off and he throws 98. With the split and slider, the guy is awesome.”

The Angels believe Arredondo has the potential to be a closer, perhaps following in the footsteps of Troy Percival, who became a pitcher after he was drafted as a catcher.

Arredondo, who grew up in San Pedro de Macoris, cradle of shortstops, was signed in 2002 as a shortstop but hit only .250 with no home runs in his first three minor league seasons.

In 2004, Butcher, then a roving pitching instructor; Ty Van Burkleo, a roving hitting instructor, and Charlie Romero, who runs the team’s Dominican academy, were watching Arredondo work out.

“He could field the ball and had a live arm, and then we saw him hit,” Butcher said. “. . . We all thought he’d have a better chance of making it as a pitcher.”

The transition started in Orem, Utah, with the Angels’ rookie-ball affiliate, where Arredondo “had a feel for the strike zone right out of the chute,” Butcher said. “The rest was kind of raw, learning how to come set in the stretch, how to throw to the bases, how to field his position.”

With his power arm and huge hands -- “He’s like E.T., only he has five fingers,” Scioscia said -- the split-fingered fastball came naturally to Arredondo.

He split 2006 as a starter between Rancho Cucamonga and Arkansas and was converted to a reliever in 2007, the year his transgressions nearly got him released.

But the Angels, criticized for giving up too soon on relievers such as Bobby Jenks and Derrick Turnbow, stuck with Arredondo, counseled him, nurtured him, and are now reaping the benefits.

“The real litmus test is consistency over the long haul,” Scioscia said. “This guy faced hitters two or three times last season, and they were still not getting good looks at him. That makes us feel good about where Jose is now and his prospects for being a major part of our bullpen. He absolutely has closer stuff, closer mentality.”

And Preston Gomez closer to his heart.

--

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.