His heart belongs to Dada

The job is gone, the 401(k) is gutted, college tuition is due, and “Grey’s Anatomy” is a shadow of its former self. Can’t decide whether to cry or laugh? Laugh at absurdity, laugh at hardship, laugh at poverty, says Andrei Codrescu in his maddening, enlightening, self-contradictory, highly amusing new book, “The Posthuman Dada Guide: Tzara & Lenin Play Chess.” It’s what dada -- the manic, prankish art-cult of wartime and depression -- advises.

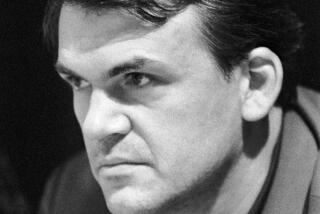

Codrescu, the NPR commentator and author, has rolled into one slim guide a postmodern self-help manual, a history lesson, a love letter to dissident poets, a hard jab at communism and a veiled autobiography. Dada was the name given to the collection of unholy noises, obscene poems and Picasso etchings displayed in Zurich’s Cabaret Voltaire in 1916 by a motley assembly of war refugees, among them French poet Tristan Tzara, Hugo Ball and his wife, Emmy Hennings. Marcel Duchamp, with his rotated urinal, became the most famous Dadaist, although he eventually renounced everything except chess -- a very Dada gesture itself.

Dadaists were anti-everything, including art, so it wasn’t much of a coherent aesthetic, and that was the point. Ideologies were out, flexibility, irony and free love were in. They were ur-bohemians, whose predecessors and heirs include Walt Whitman, Allen Ginsberg, yippies, hippies and punks. Dada, says Codrescu, still has much important nonsense to impart.

--

Tzara meets Lenin

Codrescu writes in the Dada spirit of self-contradiction. “It is and it was always foolish and self-destructive to lead a Dada life. . . . On the other hand, the accidental production of novel objects results occasionally from the practice of Dada.” Not every passage makes that much sense.

The guide is filled with random-seeming entries: “dada, bucharest” is here but not “dada, paris” or “dada, new york,” although the entry on Americanization lauds the transformation of European intellectuals who came here into open, self-actualizing, bold scavengers of high and low culture. Dada was against sentimentality, but Codrescu has a tendency to romanticize Tzara, Dada and America, in that order.

There is an actual plot embedded within the entries: Tzara and communist Russian exile Vladimir Lenin meet at another Zurich cafe in 1916 and take up a game of chess: At stake is the global state-of-mind for the next 100 years. During the game, Lenin strokes his pawns absent-mindedly, straight out of central casting for evil: His brain is a “basin full of maddened snakes furiously eating each other.”

The meeting and other fascinating facts are inventions, although much of Codrescu’s information is actually corroborated by history. Tzara was born Samuel Rosenstock in Moinesti, Romania, to a Jewish family in “an anti-Semitic town that to this day . . . does not list on its website the founder of Dada among notables born here.”

This leads to the emotional center of the book, an indictment of totalitarianism and anti-Semitism. The guide is, beneath it all, a mournful celebration of the achievements of pre-communist Romanian Jews, such as Tzara and modernist painter and architect (and Dadaist) Marcel Janco.

--

Romanian emigre

Codrescu himself immigrated to the United States from communist Romania in 1966. Within the curious entry for “jews,” he departs into autobiography, noting dryly that while 300,000 Romanian Jews, including his mother, lived through the Holocaust, 300,000 others were deported and killed.

Codrescu does not talk much about Hitler: He is battling the madness of all rigid philosophies through the embalmed body of Lenin. It’s giving away nothing to say that Lenin’s final move is easily countered by Tzara. And it’s infinitely entertaining to see how and with the aid of whom Tzara triumphs.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.