Movie review: ‘Carlos’

Into a bit-stream world of 140-character communiqués, where two-hour movies are deemed tedious before the house lights go down, comes a defiant “Carlos.” This hypnotic and sprawling five-hour-plus piece of cinematic genius from master French filmmaker Olivier Assayas lets its socio-geo-political tensions twist through two decades, beginning in the ‘70s, when the infamous, Venezuela-born international terrorist Ilich Ramírez Sánchez, code name Carlos, stalked his way across Europe.

Rooted in a rich blend of historical fact and Assayas’ imagination, the film unfolds in three parts and was designed from the outset to have a life both on the big screen and small. To that end, it will begin a run Monday on the Sundance Channel, and have a theatrical release at the Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood beginning Oct. 22, in its fully concentrated, five-and-a-half-hour form (there is an intermission roughly two-thirds of the way in).

FOR THE RECORD:

“Carlos”: In the review of the film “Carlos” in the Oct. 11 Calendar section, a passage was jumbled during production. As printed, the sentences read: “It ends just as the most infamous of his operations —taking the OPEC ministers hostage in 1975 -- is a brilliant dissection from inside, capturing the cross-currents of fear and feigned camaraderie. Increasingly bloated and dissipated, physically and mentally, the hunter has become the hunted, and neither Carlos nor the film are as comfortable with that state.” The passage should have read: “The most infamous of his operations -- taking the OPEC ministers hostage in 1975 -- is a brilliant dissection from inside, capturing the cross-currents of fear and feigned camaraderie. As we reach the movie’s end, the once taut terrorist is increasingly bloated and dissipated, physically and mentally -- the hunter has become the hunted and neither Carlos nor the film are as comfortable with that state.”

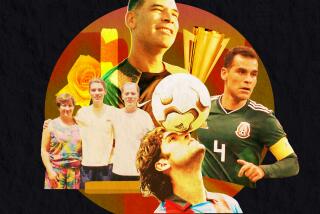

Whatever format you choose, make time for the chilling intellectual and emotional provocation of this film, though, having seen it both ways, I’d argue for taking the theatrical plunge, for “Carlos” is made for the immersive experience. Assayas has created something so alive that in the communal darkness of a theater you almost choke on the cigarette smoke that thickens the air; the sexual encounters are so visceral, the sweat and stink is palpable; and the brutality is so fueled by rage your own blood runs cold as someone else’s pools. And you can watch undistracted the singular transformation of actor Edgar Ramirez (“Che,” “The Bourne Ultimatum”) as he crawls so deeply inside Carlos’ skin that you understand why he needed therapy after a grueling shoot that stretched over seven months.

In the end the collaboration between Ramirez and Assayas creates a fiercely astute portrait of a terrorist that neither romanticizes nor demonizes him, but rather dismantles the myth to take some measure of the man underneath. It also brings a searing insight into the early days of the guerrilla-warfare-writ-large style of attack that would evolve into the sort of terrorism we fear most today.

Though based in fact and researched and written by Assayas and Dan Franck, over two years in which the director broke to make 2009’s “Summer Hours” (a beautifully constructed set piece on family, death and the push-pull of old traditions in modern times), “Carlos” is a fiction. Assayas calls it a novel. (The real man is now serving a life sentence in a French prison and had no involvement with the film.)

From the first frame, Assayas drops you into the world that inflamed Carlos’ political passions. A car bombing in Paris kills Mohammed Boudia, thought to have run the Black September cell behind the 1972 massacre of Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics. Cut to Carlos in Beirut, possibly tailed, shifting from taxi to motorcycle as he makes his way into the underground resistance to jockey for position with Wadie Haddad (an excellent Ahmad Kaabour), head of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, who makes him the PFLP’s No. 2 in Europe. He is a cocky 24 at the time and has been only loosely associated with the PFLP while he studied economics at the University of London.

The film follows Carlos’ rise within the organization as he orchestrates and executes a number of brazen attacks, some bungled but still enough of a shock to the vox populi to get the news coverage necessary to stoke fear. The most infamous of his operations — taking the OPEC ministers hostage in 1975 — is a brilliant dissection from inside, capturing the crosscurrents of fear and feigned camaraderie.

Increasingly bloated and dissipated, physically and mentally, — the hunter has become the hunted and neither Carlos nor the film are as comfortable with that state.

The task is complicated by having to set the political context while introducing a huge cast of characters, more than 120 from 10 different countries, most critically Lebanon, France, Germany, Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Hungary and Sudan. The central ensemble that washes in and out of his life is exceedingly well-drawn and much of what we learn of the man and his politics comes from those interactions.

Working with cinematographers Yorick Le Saux and Denis Lenoir, Assayas keeps the pace fast and the intensity at an unsettling high as the film shifts between terrorists’ actions, news reports, political debates, personal relationships and the evolving strategist that Carlos is becoming. He is both player and playboy, and Ramirez’s sheer charisma on screen makes you regret the few frames he’s not there to fill. It is a testament to the interplay of the images and the dialogue, which never fail to illuminate and yet never state the obvious, that despite the complexity, you never lose your way in the maze of arms trading, political maneuvering and death, always death.

During Carlos’ particular terror season, pre- 9/11, it is chilling to see how easy it was for those with mayhem in mind to walk into airports with rocket launchers barely concealed in duffel bags, or carry weapons, money and explosives on flights, plant car bombs and walk away undetected. It was an era when countries did still negotiate with terrorists, a bargaining chip Carlos used most visibly in the OPEC incident, demanding and getting a DC-9. that ultimately flew both terrorists and hostages from Algiers to Tripoli then back to Algiers, as Carlos searched for asylum.

The narrative moves from language to language as Carlos travels from country to country. Ramirez, who is fluent in five languages, uses his Spanish, French, German and English, as well as the Arabic he learned for the production, so seamlessly that you absorb without remembering just how.

Whatever there is to be learned about the terrorist mind, what Assayas has done more tellingly is remind us of the sheer immersive force of the historical epic, a genre that has all but disappeared from the big screen. “Carlos” is already destined to stand alongside the greats, where substance and artistry trumped length — “Lawrence of Arabia,” “Doctor Zhivago,” “Reds.” My hope is that it won’t be the last, but the beginning.

betsy.sharkey@latimes.com

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.