Publishing’s panic seems to subside in 2013

Toward the end of September, I found myself in a meeting room at Brooklyn Borough Hall in New York with planners from a variety of book fairs (Miami, Trinidad, Texas, Australia) discussing audience and cooperation and outreach. It was the morning after the Brooklyn Book Festival, which had drawn tens of thousands, and the atmosphere was upbeat, marked by excitement, even relief.

Economics remained an issue (how to attract and pay for writers, how to advertise and promote) but there was no lamenting, no sense that things might be shutting down. Rather, with a number of new festivals represented, the conversation was expansive, peppered with optimism about the future of reading and books.

This is the story, for me, of 2013: that there is no story, or more accurately, that the panic that’s defined publishing for the last several years has calmed. Yes, uncertainties linger — about the relationship between print and electronics, about how writers get paid in an increasingly digital economy — but there is also the sense that we are settling into a tenuous new balance.

PHOTOS: David L. Ulin’s top books of 2013

Last week, Matt Pearce wrote in The Times about online outlets (Pitchfork, the Los Angeles Review of Books, the New Inquiry) that have begun to turn to print; in November, the British market research firm Voxburner conducted a survey in which more than 60% of respondents ages 16 to 24 preferred reading print on paper to pixels on screen.

Considered alongside information that e-book sales appear to have flattened, as Nicholas Carr has reported, at “a bit less than 25 percent of total book sales,” this suggests a more complicated story, in which it is diversity rather than dominance that resonates, and publishing starts to look more like an ecosystem than merely an industry.

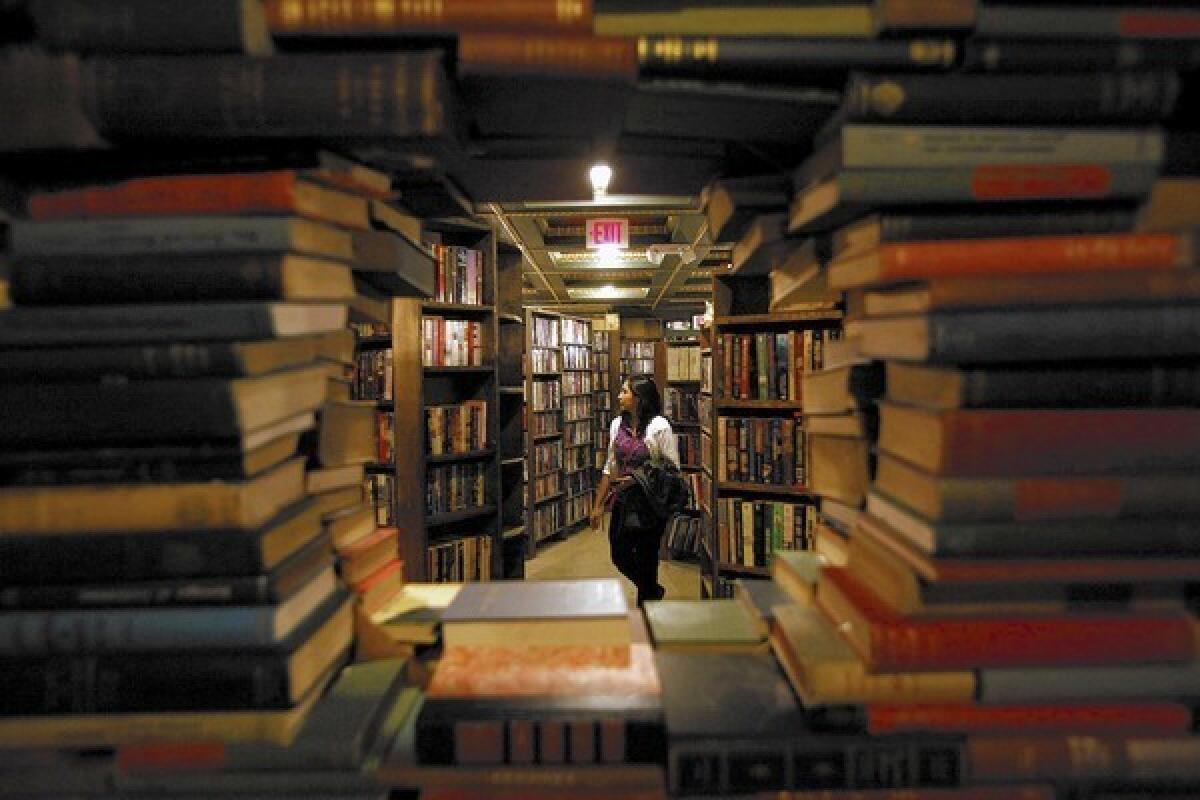

What’s most compelling about such an ecosystem is that it is not generally top-heavy but bottom-up. It begins with independent bookstores, which have seen a renaissance of sorts. According to the American Booksellers Assn., sales rose by 8% in 2012, and similar numbers are expected in 2013.

This may seem surprising in a landscape where Amazon’s recent announcement that it intends to use delivery drones qualifies as a buzzy story, but then Amazon has never been about book culture. Sure, it offers a way to get books fast when you know what you’re after or to buy a bestseller at a cut-rate price.

Most readers, though, want more than cheap books; we want conversation, community. Hence, Amazon’s purchase of Good Reads, for $150 million or so, at the end of March. And yet, this is where independent bookstores excel organically, in their relationship to neighborhood clientele.

“This bookstore was kind of a steppingstone to … integrate myself into the local community,” a customer named Jessica Brown told NPR last month, describing Seattle’s Mockingbird Books. There’s something touching about the interaction she describes.

Call it local, call it artisanal, call it slow reading: I call it a mechanism by which we are enlarged. That, in turn, goes back to why we read in the first place: not to be entertained or distracted but to be connected, to experience a world, a life, a set of emotions we might not otherwise get to know.

At the heart of this is, again, diversity — of voices, venues, points of view. That’s the promise of a digital universe, although a recent report from Digital Book World offers sobering perspective, noting that 19% of self-published authors “reported no annual income from their writing” and that as a group they “earned a median writing income of $1 to $4,999” — lower than their traditionally published counterparts, who “had a median writing income of $5,000 to $9,999.”

The good news is that, in a bottom-up infrastructure, independent publishers are increasingly able to break through. I think of D.A. Powell and Mary Szybist, both published by Minneapolis’ Graywolf Press, who won the National Book Critics Circle Award and the National Book Award in poetry, respectively. I think of Pulitzer finalist Lore Segal publishing her new novel “Half the Kingdom” with Brooklyn’s Melville House, or Hilton Als, whose magnificent “White Girls” came out from McSweeney’s in the fall.

That’s not a new development; indies have taken advantage of territory ceded by the majors for nearly two decades, and this has really exploded in the last five years. But in the context of this year, with its relative (dare we say it?) stability, it feels like a bit of reassurance, the whisper of a new normal, in which there may be room for everything, after all.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.