Lil Wayne’s Rikers Island memoir ‘Gone ‘Til November’ is a missed opportunity

America is home to one of the world’s largest and most notorious penal colonies: Rikers Island in New York. In it sit more mentally ill individuals than all of the state’s psychiatric hospitals combined. Eighty percent of its residents have been convicted of nothing and cannot afford bail; 89% of them are black or Latino. In 2014 one such pre-trial detainee, homeless veteran Jerome Murdough, died of hyperthermia in a Rikers cell that was over 100 degrees. Kalief Browder was arrested at age 16 for allegedly stealing a backpack and imprisoned there for three years, sans conviction — then committed suicide in 2015. In addition to these deaths and others, scores of extreme assaults have been discovered by those investigating the facility, which has come under fire for its culture of brutality.

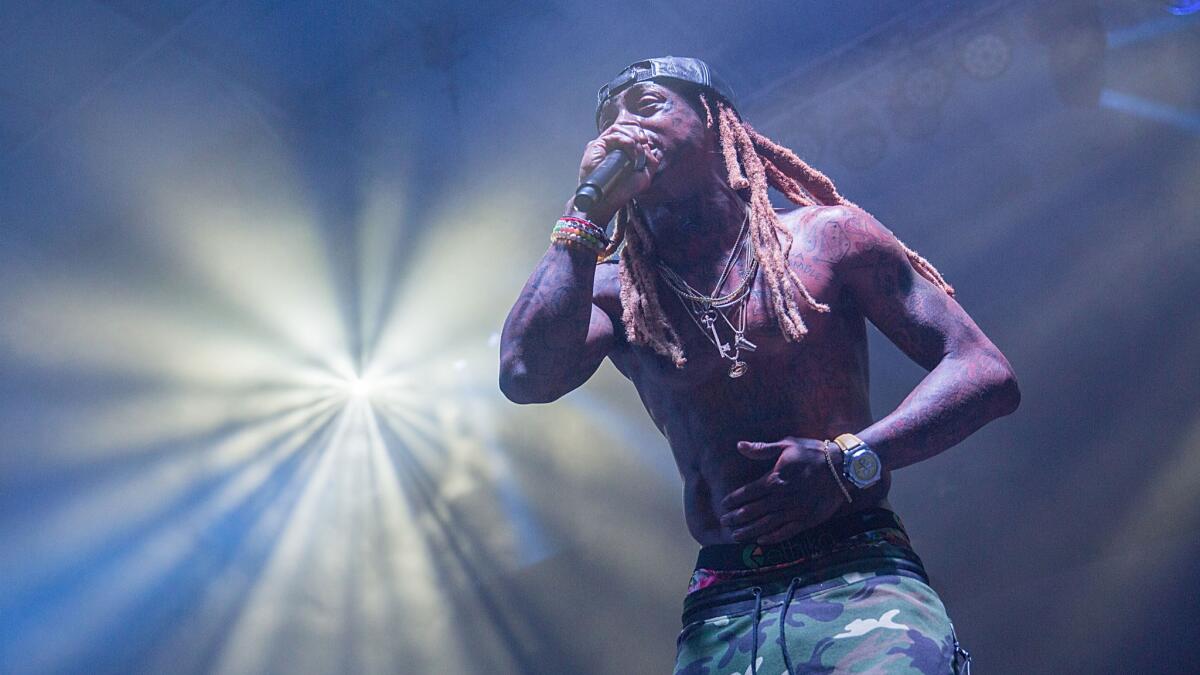

You would know none of this reading “Gone ‘Til November,” rapper Lil Wayne’s flimsy account of eight months incarcerated on Rikers some five years ago, for criminal possession of a weapon. Behold his greatest stresses: there’s a mouse on his tier, he oversleeps, he’s putting on weight, his neighbors fart all the time. The portrait of Rikers that emerges from his book, a series of insipid journal entries, is of a mildly unpleasant, vexingly dysfunctional place akin to, say, the DMV—or, as he puts it, “the music biz, only without the female groupies.”

Alas, it should not be so. “Gone ‘Til November,” is a flagrant missed opportunity, landing at a moment when mass incarceration is at the forefront of U.S. civil rights discourse and Rikers, in particular, is the subject of intense public scrutiny and a robust campaign, #CLOSErikers, demanding its closure.

U.S. Atty. Preet Bharara has blasted Rikers’ “systematic culture of violence,” saying the jail’s treatment of adolescent inmates is “more inspired by the ‘Lord of the Flies’ than any legitimate philosophy of humane detention.” One of the students in my Prison-to-College Pipeline program put it more bluntly — after a stint there during which he and hundreds more stood through the night because they feared being attacked in their sleep: “I was sure I’d die.”

Just as the 19th century produced powerful slave narratives that changed hearts and minds about that peculiar institution, now is the era of the prison narrative, with feted formerly incarcerated authors such as Shaka Senghor (in “Writing My Wrongs,” 2016) and Dwayne Reginald Betts (“A Question of Freedom,” 2009) putting a human face on the problem that is our prison system. An illustrious lyricist, Lil Wayne could have been the celebrity voice in this mix and the voice of hip-hop, a vital intervention given how many rappers — Foxy Brown, Shyne, Tupac Shakur, DMX, T.I., to name a few — did time but penned little about it.

Instead he gives us prison clichés: push-ups, phone calls, girlie magazines, culinary cell concoctions (Doritos burritos are a favorite), makeshift ingenuities (air freshener made from orange peels), commissary vexations, visits (from folks like Kanye West). In lieu of genuine pathos come a plethora of exclamation points and monosyllabic outbursts: “damn!” means he misses his mother; “yeah!” means his corrections officer friend “White” — “my dude,” he calls him — brings him extra sugar for his coffee. “The only time that I can have anything close to a normal conversation is with a CO,” [corrections officer] he writes, dismissing his incarcerated peers in one fell swoop. “I’ve never been this close to suicide before,” he declares, then follows that jarring statement with a happy ending, 20 pages later: “I’ve never felt more creative in my life!”

Murmurs of horrific Rikers realities are mere background noise, making them that much more pause-worthy. Wayne writes of “late-night screamers” keeping him awake, of showering in puddles of blood, of his friend “Jamaica” getting deported (“I guess he really did need a better lawyer. Damn!”) and, most appallingly, his job as a suicide prevention aide, for which he is paid $50 to stop a person from hanging and $25 to find him hanged (“you should see me with my little flashlight and all, haha”).

Ultimately, the one redeeming aspect of “Gone ‘Til November” is encapsulated by a seven-word chapter titled “Bad Day”: “No writing, prayer, Bible, sleep. Another one.” While the trauma of a prison stay is usually, and sensationally, depicted in terms of physical violence, prison’s psychological violence — the monotony, the loneliness, the isolation and depression — is occasionally captured by Wayne’s spare, mundane, repetitive language. “Jail is nothing but a whole lot of … nothing,” he writes with an expletive. In that “nothing,” though, is a whole lot of something; it’s a grand shame that a rapper as verbally dexterous as Lil Wayne did not elucidate it.

Dreisinger, a professor of English at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, is the Founding Academic Director of the Prison-to-College Pipeline and author of “Incarceration Nations: A Journey to Justice in Prisons Around the World.”

::

“Gone ’Til November: A Journal of Rikers Island”

Lil Wayne

Plume: 176 pp., $23

MORE FROM JACKET COPY:

In Connie Willis’ ‘Crosstalk,’ sci-fi meets romance in an overcommunication age

Maria Bamford’s favorite self-help books

Jay Z’s answer to police brutality against black men: compassion, not cameras

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.