Amiri Baraka captured an outsider’s anger, giving it beauty

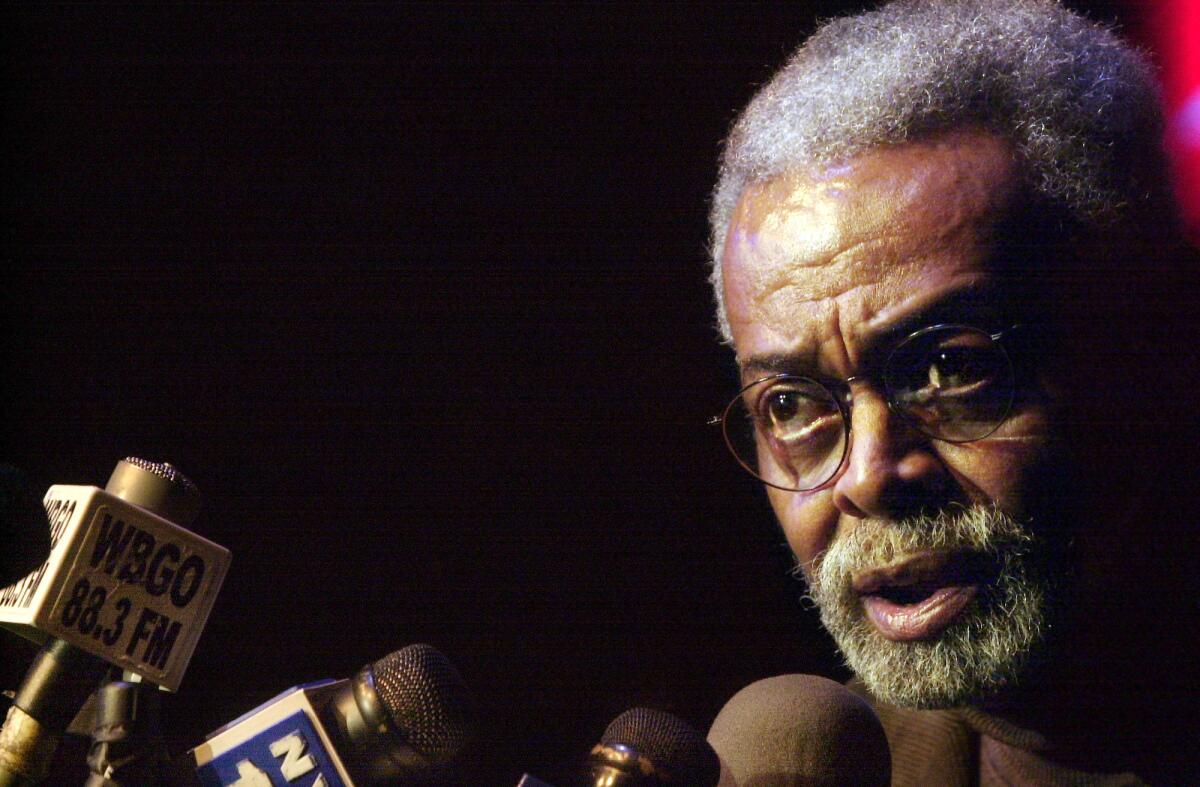

Once you had met him, the poet Amiri Baraka was a tough man to forget.

I saw Baraka read once, here in Los Angeles, at the Beyond Baroque literary center in Venice, circa 1990. He was already white-haired and white-bearded then, and he cut a not-especially-happy-to-there pose as he stood behind the lectern, reciting some of his newer work.

When he had finished, an enthusiastic member of the audience yelled out the names of some of his poems from the 1960s and ‘70s. I don’t remember which ones, but perhaps it was one like “An Agony. As Now,” written when he lived in New York, haunting jazz clubs, and when his goatee did not hold a hint of gray.

That poem begins with the writer in an existential crisis: “I am inside someone/who hates me. I look/out from his eyes. Smell/what fouled tunes come in/ to his breath. Love his/wretched women.” And it ends with the writer trying to fight his way out of it: “It burns the thing/inside it. And that thing/screams.”

A certain kind of American reader loved Baraka for capturing an outsider’s anger, and giving it form and voice and beauty. Even his name was a kind of poem: The former LeRoi Jones took a name that meant “blessed prince” in Swahili. His fans that night wanted Baraka to be that poet again. But Baraka didn’t like to think of himself as a performer. He looked up at us from over the tops of his glasses and gave us all an irritated look.

“I’m not reading any of those poems tonight,” he said, and that was that.

Baraka’s life carried him across a variety of American literary and social movements: from The Beats to Black Nationalism to Marxism. He “joined” each movement when it was still a dangerous and edgy thing to do, and floated away from each movement when it became more settled and mainstream. In his later years, he seemed to embrace being irascible and provocative for its own sake, as with the poem he wrote (as poet laureate of New Jersey, no less) following the 9/11 attacks. It repeated the canard that “4,000 Israeli workers” had stayed away from the World Trade Center towers because they had been forewarned of the attack.

I liked that Baraka wouldn’t cater to his audience that night at Beyond Baroque. But I wouldn’t have minded at all if he’d acquiesced and read some of those older poems too, because they joined together his anger with his humanity, compassion and love of language. His political statements, by contrast, had all the subtlety of pornography, with ample use of fascist and Third Reich analogies.

At Rutgers in the 1990s, he compared his academic foes to Goebbels. But his poetry could be magic, and called forth magic often, as in the beautiful manifesto of Ka’Ba.

“We have been captured,/and we labor to make our getaway, into/the ancient image; into a new/Correspondence with ourselves/and our Black family. We need magic/now we need the spells, to raise up/return, destroy, and create. What will be/the sacred word?”

ALSO:

Does grammar matter? Yes, it does.

Randall Mann and the poetics of desire

Long-lost Mary Shelley letters surface after more than 150 years

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.