Gabriel Garcia Marquez was more than magical realism: An appreciation

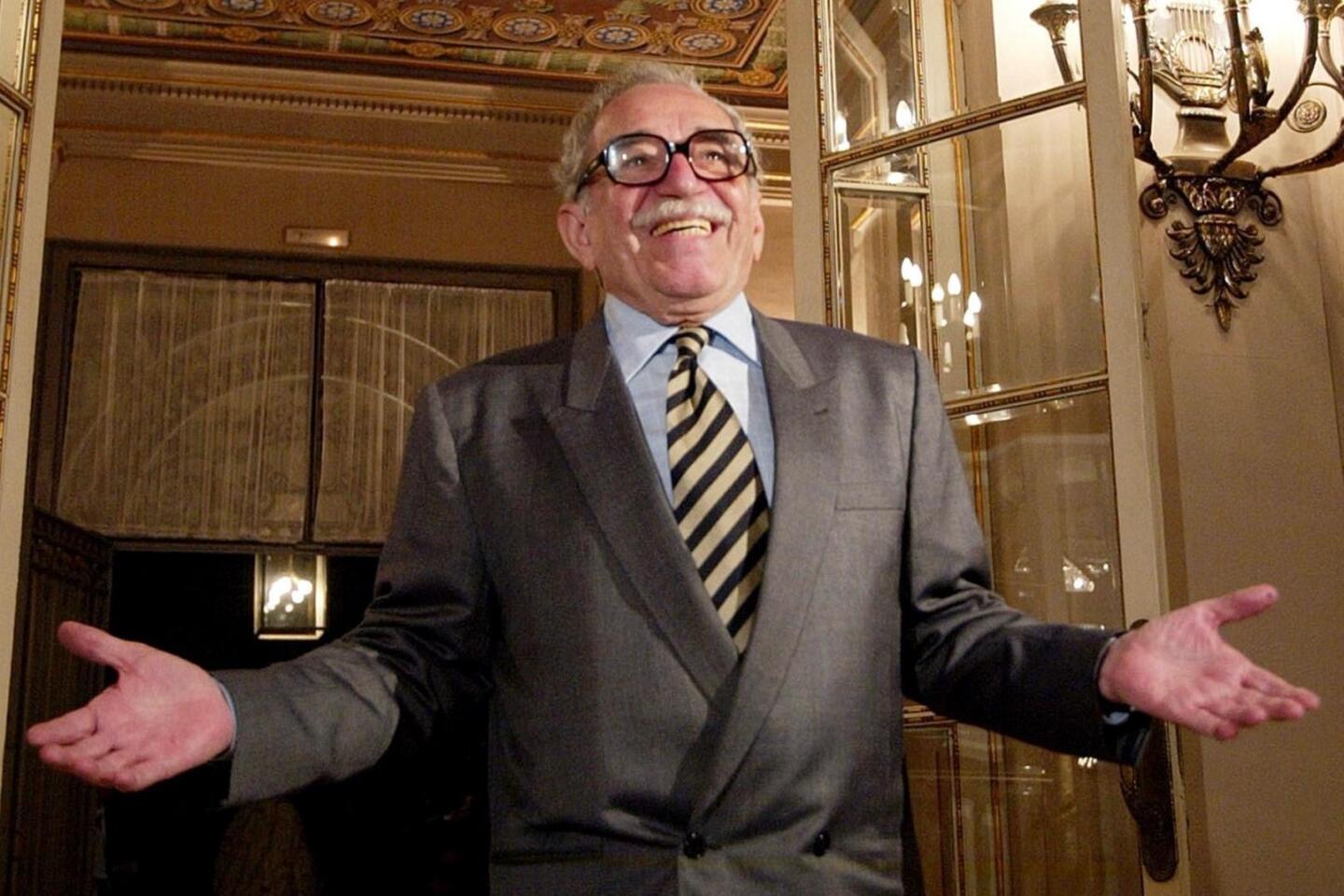

Gabriel Garcia Marquez was a charmer.

The great Colombian novelist, who died Thursday, called Mexico City home for much of his life, and it was there that I met him, at a chi-chi Mexican restaurant where he agreed to a sitdown with a half-dozen Times foreign correspondents and editors in 2004.

Behind his thick glasses and looking frail even then, the author treated us as if we were the celebrities at the table. He’d love to visit our newsroom in Los Angeles, he said. But he was afraid that if he entered, “I’d never leave.”

Like Hemingway, “Gabo” was a newspaperman. He’d worked as a columnist in Colombia and his first book was born as a series of columns about a shipwrecked sailor. That thin little volume with an impossibly long title was the first book I read in Spanish, as a 19-year-old Angeleno undergraduate studying the language of my immigrant parents: “The Story of a Shipwrecked Sailor: Who Drifted on a Liferaft for Ten Days Without Food or Water, Was Proclaimed a National Hero, Kissed by Beauty Queens, Made Rich Through Publicity, and Then Spurned by the Government and Forgotten for All Time.”

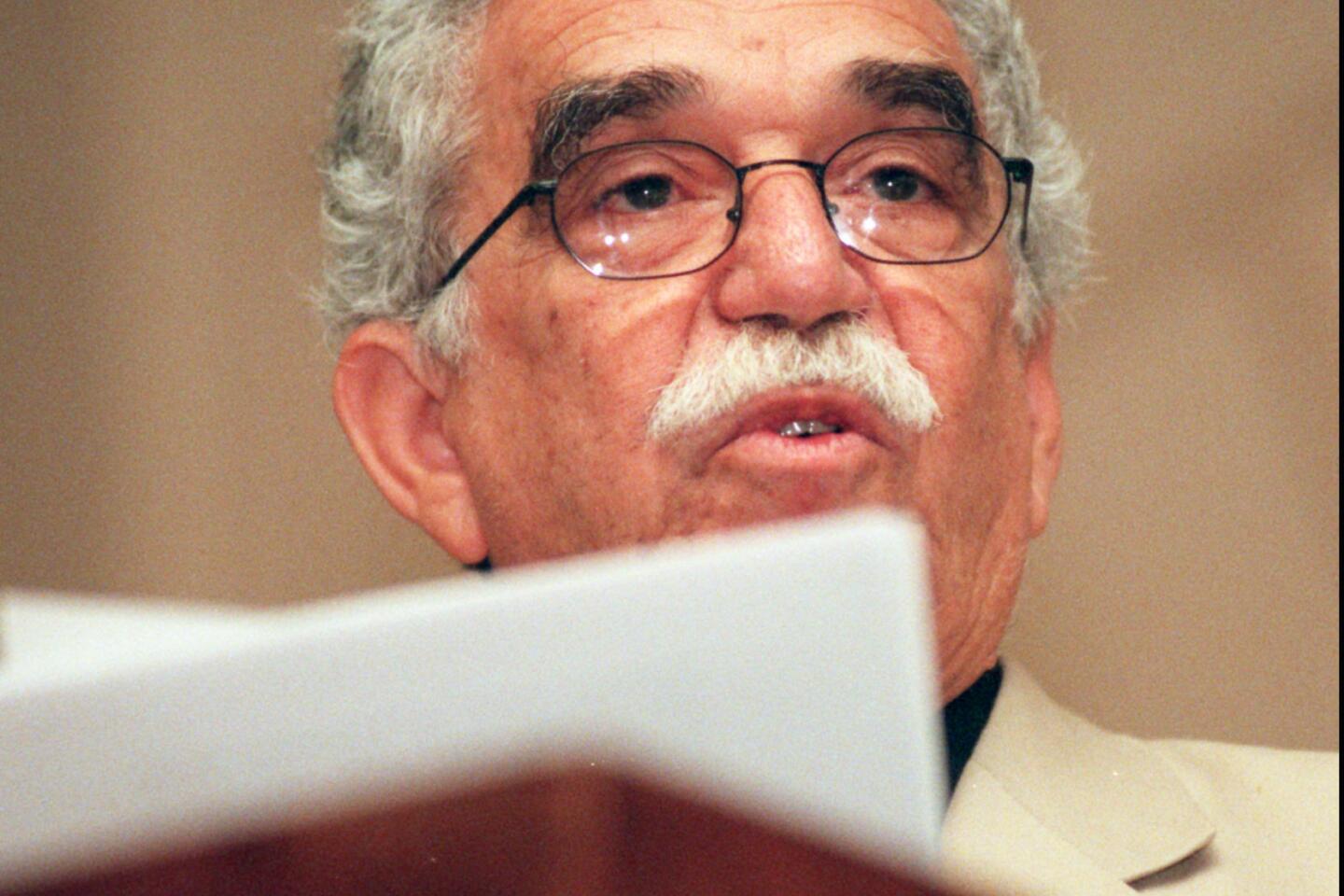

The young Garcia Marquez was a natural storyteller, a skill he attributed to his grandmother, and had a spare, lucid writing style. With a small group of other journalists with lofty writing aspirations, he began a deeper study of literature. Eventually he fused his journalistic skills to the literary voice of the American avant garde -- ”American” in the broadest possible sense of the word.

He read William Faulkner and was a younger contemporary of the writers of the “Latin American boom,” an all-star cast that included the Argentine Julio Cortazar and the Mexican Carlos Fuentes. Unlike Cortazar and Fuentes (but like Faulkner), Garcia Marquez was a provincial, from a small town.

In his greatest work, “One Hundred Years of Solitude,” he took the memories of his youth in Aracataca and the stories of his grandmother and created “Macondo,” a place where 20th century Latin American history unfolded as a series of magical and legendary happenings.

In one especially memorable scene, a group of traveling gypsies brings the first block of ice the locals have ever seen. To the people of Macondo, it’s “an enormous, transparent block with infinite internal needles in which the light of the sunset was broken up into colored stars.” One of the characters declares, “It’s the largest diamond in the world.”

Dreams and ghosts fill the pages of “One Hundred Years of Solitude.” A woman flies up to heaven. In a 1982 interview with the New York Times, Garcia Marquez said that the “tricks you need to transform something which appears fantastic, unbelievable into something plausible, credible, those I learned from journalism .… The key is to tell it straight. It is done by reporters and by country folk.”

My father grew up in a town like Macondo -- Gualan, Guatemala. Coincidentally, the same American company that dominated life in rural Colombia (and that was fictionalized in “One Hundred Years of Solitude”) also dominated life in Gualan: the United Fruit Co.

“Macondo is Gualan,” my father told me when I was in my twenties, after I’d recommended the book to him and he’d read it. In Gualan, for my father, it was not a block of ice that made the ordinary seem real, but rather the first new American truck to drive into town. “It was so shiny and new and modern, I thought it looked like a spaceship,” my father said. When I first visited Gualan as an adult -- on a battered old train that evoked many of Garcia Marquez’s novels -- I couldn’t help but feel I was being transported into the realm of the “magic real.”

The railroad depot where my grandparents met was rickety, its paint chipping, but thanks to Gabo I could imagine it in its days of glory, and more easily see it for what it was -- a place of legendary happenings for the people who lived there.

Later, as a young journalist hoping to become an author, I studied Garcia Marquez’s technique and read interviews in which he discussed his work. What shined through was the same thing I’d see in person when I met him: his humility. To fill the gaps in an education that felt inadequate to him, Garcia Marquez told us, he collected reference books. And he always expressed a deep respect for his craft and its traditions.

“Ultimately, literature is nothing but carpentry,” he told the Paris Review in 1981. “Both are very hard work. Writing something is almost as hard as making a table. With both you are working with reality, a material just as hard as wood. Both are full of tricks and techniques. Basically very little magic and a lot of hard work are involved.”

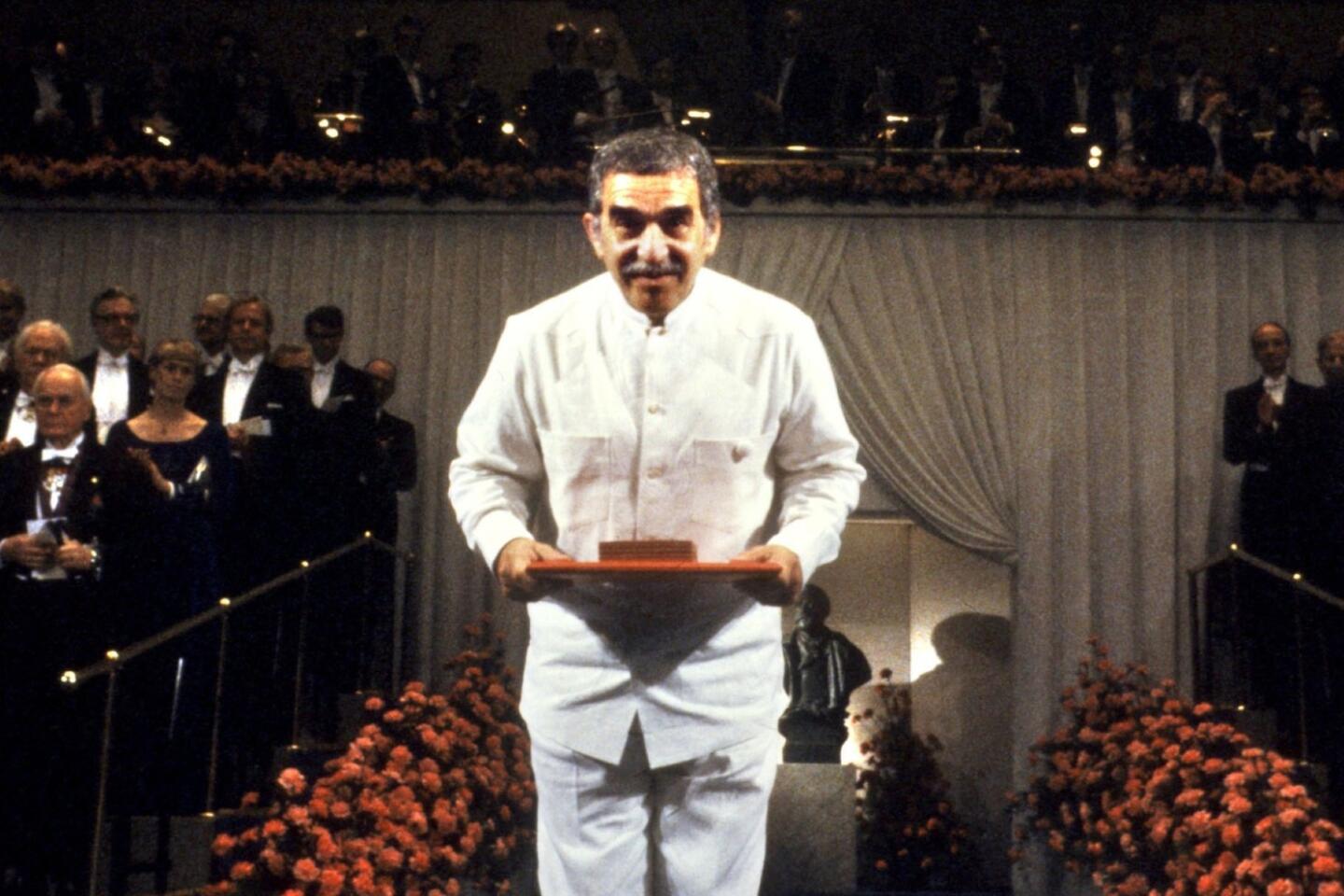

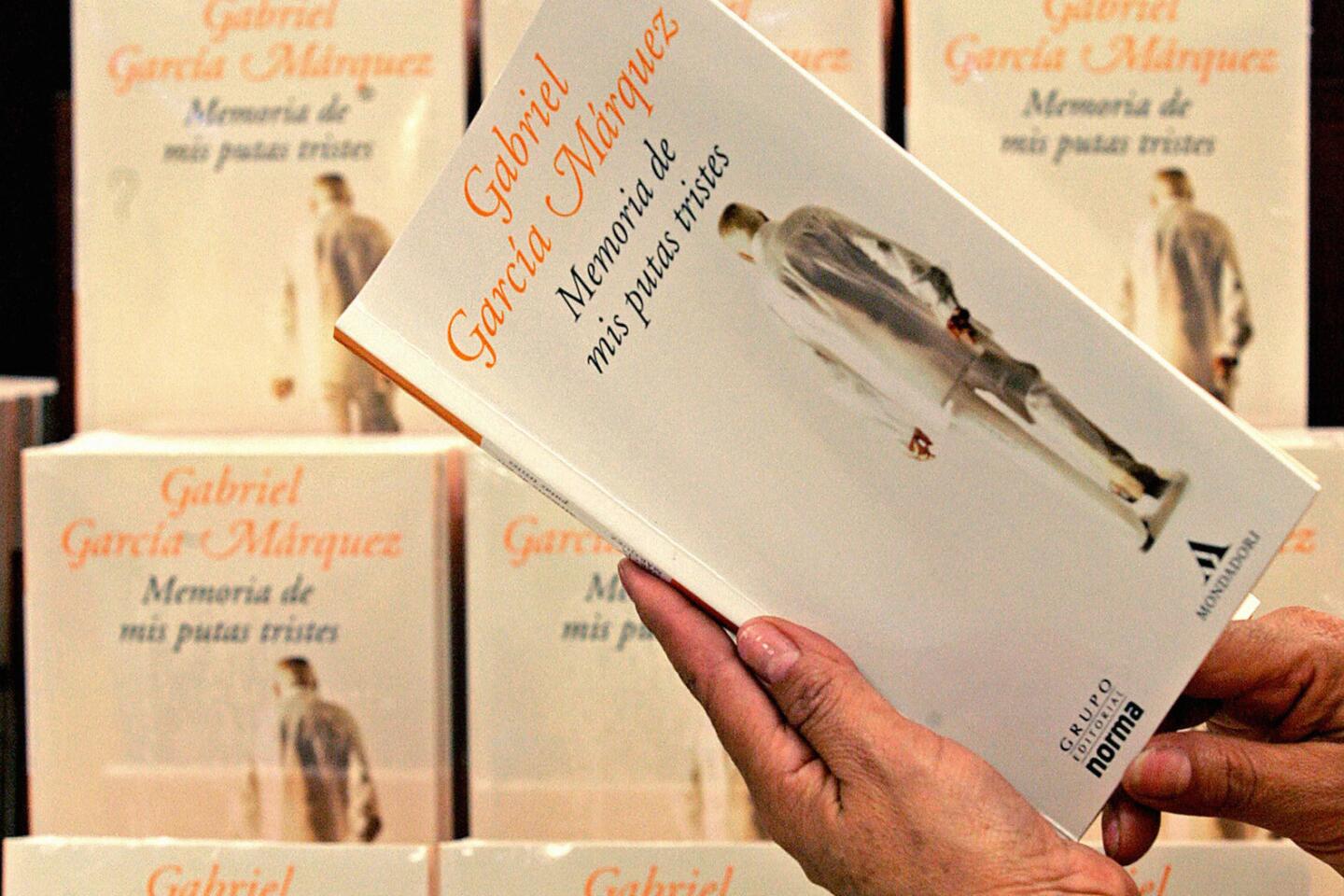

Garcia Marquez, the “carpenter,” built worlds that made the magical seem real. In so doing he sold millions of books in dozens of languages and won the Nobel Prize for literature. But more importantly, he brought the life and history of ordinary Latin American working people onto the stage of world art. And for that, this son of Latin America is deeply grateful.

hector.tobar@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.