Marina Warner on ‘Gilgamesh,’ the flood and what remains

“Myths, like inquisitive children, keep asking: why?” Marina Warner observes in an essay posted at the London Review of Books. “They answer with stories of origin and destiny, luck and catastrophe.”

If anyone should know about this, it would be Warner. A professor at England’s University of Essex, she may be our foremost authority on fairy tales. This is not, lest we think otherwise, kids’ stuff; what Warner is after, rather, is what we might call the substance of our imaginative DNA.

“Stories come from the past but speak to the present (if you taste the dragon’s blood and can hear what they say),” she has written. “… I hope, I believe that literature can be ‘strong enough to help’, to borrow Seamus Heaney’s wonderful comment about poetry.”

I share that belief, in literature as a source of solace, understanding, even (or especially) when it seeks to disturb.

This is part of the point of Warner’s essay, which uses accounts of the flood in various cultures, from Mesopotamia to the Bible, to riff on what we leave behind us, on the value of what remains. That there are so many flood stories, she suggests, does not indicate “one single universal deluge — this is accepted now even by Biblical scholars.” And yet, in the overlap of narratives, we learn something about our desire for history to cohere.

Writing of George Smith, who discovered “The Epic of Gilgamesh” in the 19th century, Warner observes that “his joy was occasioned above all by the independent corroboration the poem offered to the historicity of the Bible. He was a fervent Christian and longed, as many did, for archaeology to prove the scriptures’ reliability.”

Now, however, “Gilgamesh” stirs a different sort of promise — that of rediscovery. When Smith first shared it with the public in 1872, Warner points out, it “was the first time the ‘Epic of Gilgamesh’ had been heard and understood after an interval of two thousand years: the longest sleeper ever among the world’s great poems.” What this means, she continues, is that we read it as representing a kind of “double history, as an ancient epic and a modern narrative poem.”

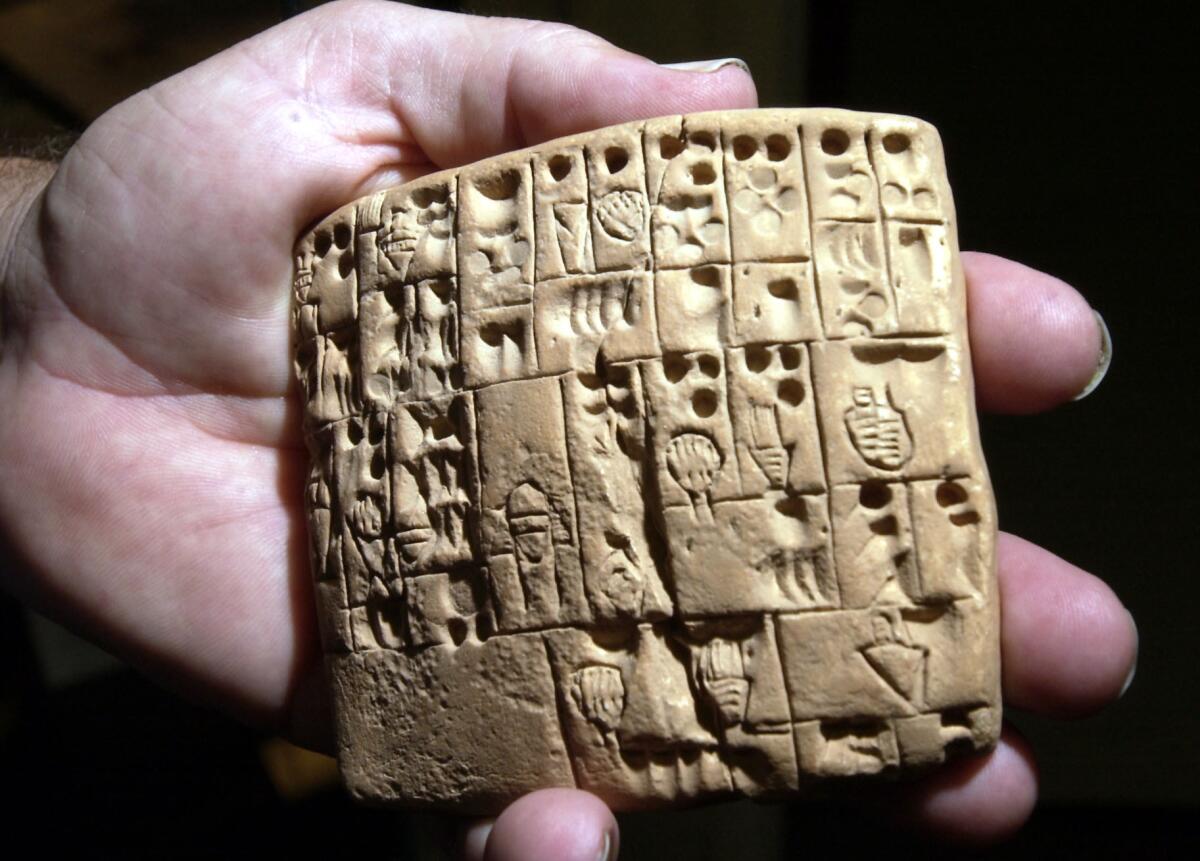

This is important, for it allows us imagine “Gilgamesh” as both story and artifact, to understand that its survival was not inevitable but a function of fortune, luck. That, in turn, reminds us of just how random our pattern making efforts are, reliant on a “jumble of stone bits and pieces,” on the serendipity of what survives.

What will linger after we have disappeared, Warner wonders, and what will it say about who we were?

“The tablets dug up at Nineveh happen in shape and size to resemble mini-iPads,” Warner notes. “If our ‘tablets’ are still there in the mud in four thousand years’ time, and humans are still around, they’ll have a hard puzzle in front of them, should they wish to recapture our words, our laments, our tweets.”

ALSO:

In praise of procrastination for writers

The great American novel? What’s that?

Writing of rain in Los Angeles -- and elsewhere

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.