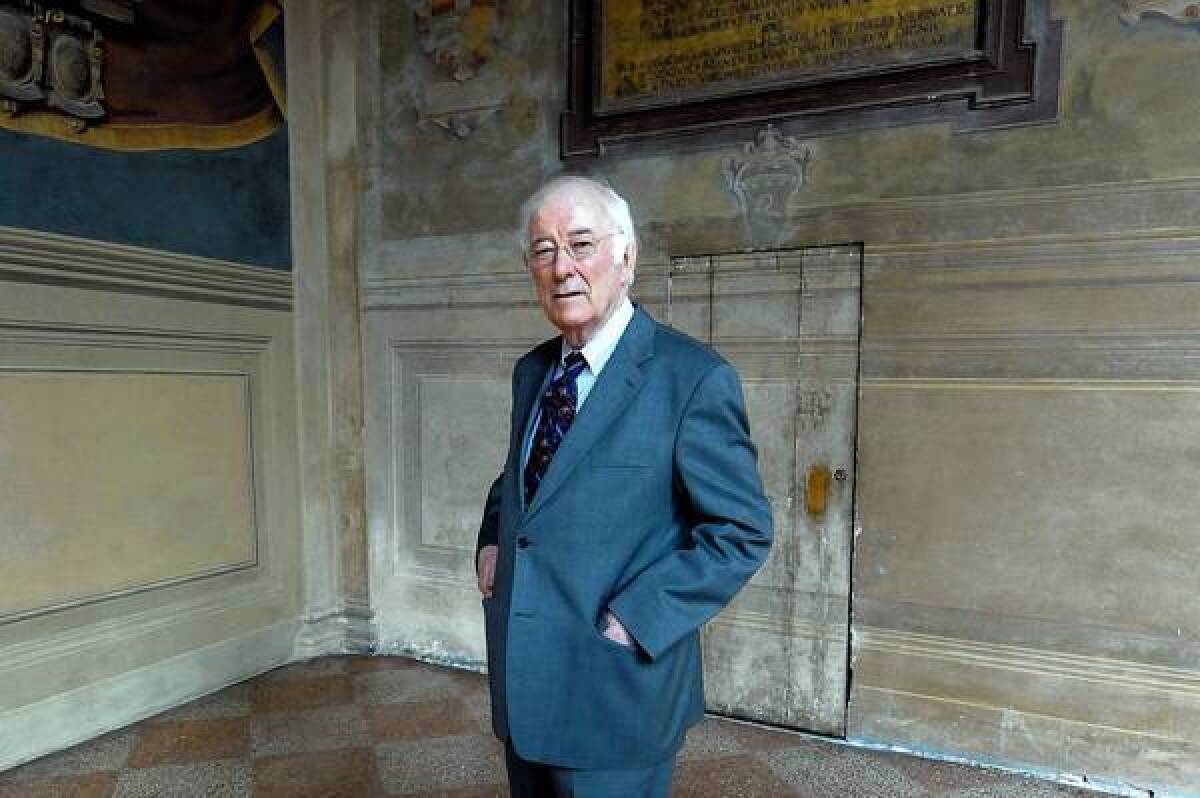

An Appreciation: Seamus Heaney, animator of words

Thirty years ago, I became a graduate teaching fellow in a popular undergraduate course at Harvard University called Modern Anglo-Irish Poetry. What made it popular? The subject matter was certainly rich. But the professor, Seamus Heaney, was the special attraction. He was already a major figure in the poetic landscape; we watched him artfully mapping its peculiar geography.

Heaney, who died Friday in Dublin at age 74, was powerful and widely read, receiving countless honors, including the Nobel Prize. With stunningly fresh language, his poetry dug deep into the roots of human attachments but also of human violence. The author of the stunning pastorals “The Glanmore Sonnets” also created the haunting Dantean poems of “Station Island.” His versions of Sophocles, “The Cure at Troy” and “The Burial at Thebes,” reached to the heart of human suffering and alienation. His work embraced a vision of hope and the possibility of seeing, as he titled one poem, “From the Republic of Conscience.” And he made a fool of Woody Allen (“Never take a course where they make you read ‘Beowulf’”) by making his version of the Old English epic a bestseller.

But Heaney was that rare thing, an unofficial international poet laureate who had become an ambassador for the entire institution of poetry.

Anyone could see that, although the mantle was something of a trial for him, he considered it an honor and a duty. Often grumbling about the need to hide, he was generous and energetic with his time. Heaney sometimes joked that he wasn’t sure whether he was a prognosticator or a procrastinator. But when invited to make judgments or pronouncements, he exhibited his flair for what he called “speaking with forked silence.”

In addition to publishing more than a dozen volumes of poetry, along with translations and several volumes of essays, Heaney spent much of the second half of his life teaching and lecturing around the world. While teaching at Harvard, he would arrange social gatherings for the teaching fellows, providing generous rounds of food and drink. He channeled our overheated graduate student intellectual energies into fun, encouraging us to sing songs or recite favorite poems. These sessions would go on for many fine hours flowing with all varieties of song and whiskey.

We both loved the work of Robert Frost, differently. There were sessions in Heaney’s apartment reciting Frost’s poems (along with Hardy, Hopkins and Yeats) and trying to figure out how best to say particular lines. It was fascinating to listen to him speculate about the right emphasis in “And to do that to birds was why she came,” the final line of Frost’s “Never Again Would Birds’ Song Be the Same.”

Few poets — even of visionary sensibility — could imbue lines with such a visceral, indelible sense of both diction and cadence. If there was a longing in his poetry, it was for a world transfigured into perfect sounds. Nothing was more moving than listening to Heaney recite one of his favorite Yeats poems, “Cuchulain Comforted.” In that poem, the wounded warrior in the underworld encounters figures who give advice, then stop speaking: “They had changed their throats and had the throats of birds.” Heaney wiped tears from his eyes when he finished and repeated softly, “I wonder what he meant. I wonder what he meant.”

Although Heaney’s reputation and fame grew considerably, he went out of his way to support poetry and poets. He also gave thousands of undergraduates his full attention in small, informal seminars. His readings were often unforgettable events, the perfectly pitched performances of a poet who wanted his words to resonate and be remembered.

He remained committed to poetry and to one of the things poetry can do: make our suffering almost bearable, whether, as he wrote in “St. Kevin and the Blackbird,” in a “land of dreams or a darkling plain.”

Faggen is the Barton Evans and H. Andrea Neves professor of literature at Claremont McKenna College.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.