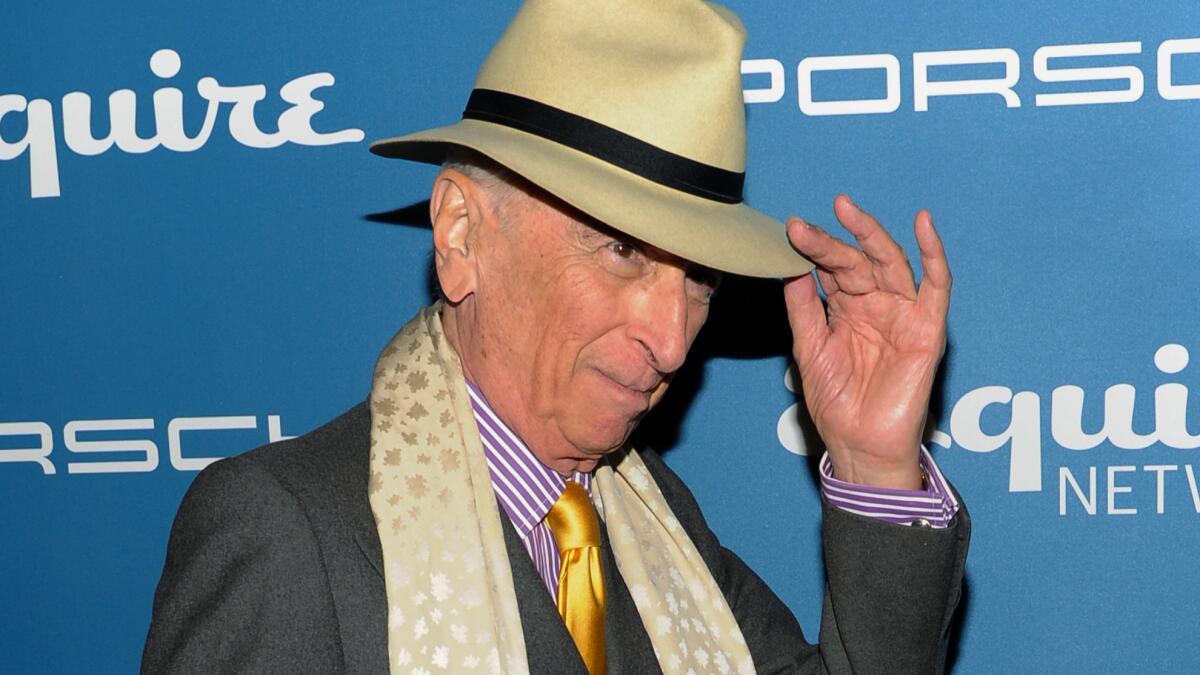

Gay Talese’s book ‘The Voyeur’s Motel’ got the author in hot water. But is it any good?

What happens to a book when the news about it — the side story — begins to overwhelm the sentences and paragraphs? That’s one of the dilemmas around Gay Talese’s “The Voyeur’s Motel,” which the author briefly disavowed recently after the Washington Post uncovered discrepancies in its chronology.

According to the Post, Talese’s subject, Gerald Foos, who spied on the sex lives of his guests for nearly 30 years through vents leading to a secret attic crawl space in his suburban Denver motel the Manor House, actually sold the motel in 1980 and reacquired it in 1988.

In response, Talese declared he wouldn’t promote the book, before backtracking the next day. In a statement issued by his publisher, Grove Press, Talese said he would stand by his work. “[Foos] could … at times be an unreliable teller of his own peculiar story,” he explained.

Talese is right: Among the tensions that mark “The Voyeur’s Motel” is that of Foos’ credibility. “Indeed,” the author writes, “over the decades since we met, in 1980, I had noticed various inconsistencies in his story: for instance, the first entries in his Voyeur’s Journal are dated 1966, but the deed of sale for the Manor House, which I obtained recently from the Arapahoe County Clerk and Recorder’s Office, shows that he purchased the place in 1969. And there are other dates in his notes and journals that don’t quite scan.”

So too the stories Foos recounts. Quoted extensively — so much so that in places, Talese’s writing comes off as little more than set-up for what Foos calls “The Voyeur’s Diary” — these read, for the most part, like perversion more than research, which is how he characterized his activities.

“Since Gerald Foos was frequently carried away by fantasies of his significant scientific status,” Talese tells us, “… his written reports often conveyed the professional tone of a sexual therapist or marriage counselor.” Indeed, this was how Foos approached Talese, just before publication of “Thy Neighbor’s Wife,” the latter’s extensive examination of American sexual practices and mores.

Talese, of course, is one of the innovators of what has come to be called New Journalism — the author of a dozen books, as well as a number of groundbreaking magazine pieces. His “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” written in 1966 despite Sinatra’s refusal to be interviewed, has become a staple in creative writing and journalism classrooms.

“Dear Mr. Talese,” Foos began their correspondence. (Later, he would insist Talese sign a confidentiality agreement.) “Since learning of your long awaited study of coast-to-coast sex in America, … I feel I have important information that I could contribute to its contents or to contents of a future book.”

Researchers, however, don’t routinely masturbate to the activities of their subjects, nor do they spy on people without their consent. Talese acknowledges that, although throughout “The Voyeur’s Motel,” he leaves it something of an open question as to how much he, or we, are meant to trust Foos — or perhaps more accurately, how much Foos can trust himself.

Foos’ original letter must have felt to Talese like a sort of gift: a one-of-a-kind character offering up his inner life.

— David L. Ulin

It all comes to a head on the night of Nov. 10, 1977, when Foos claims to have witnessed a homicide. The victim is a young woman, strangled by her drug dealer boyfriend, who decides she’s stolen his supplies.

Foos, however, is complicit — he admits, in his diary, having removed the drugs himself, as he routinely did when he observed their use or sale. That makes him an accessory, as does his unwillingness to reveal to law enforcement everything he knows.

Talese also admits feeling compromised after reading of the killing in Foos’ diary: “I spent a few sleepless nights asking myself whether I ought to turn Foos in or continue to honor the agreement he had asked me to sign.”

This material caused its own tempest when the New Yorker excerpted “The Voyeur’s Motel” in April; was Talese responsible, some readers wondered? Had he crossed into ambiguous moral territory, where journalistic ethics come up against (or even, potentially, into conflict with) those of the culture at large?

I don’t think so. Journalists traffic with unsavory sources all the time, and Talese, for his part, never endorses his subject’s behavior, even when (as he must) he goes along for the ride.

After Foos offers him a glimpse of his operation — they nearly get caught as the author’s tie slips “through the slats of the louvered screen” into a room where a couple is engaged in oral sex — he finds not titillation but something far more desperate. “As I looked through the slats,” Talese tells us, “I saw mostly unhappy people watching television, complaining about minor physical ailments to one another, making unhappy references to the job they had, and constant complaints about money and the lack of it, the usual stuff that people say every day to one another….To me, without the Voyeur’s charged anticipation of erotic activity, it was tedium without end, the kind acted out in a motel room by normal couples every day of the year, for eternity.”

And yet, what of that homicide? It’s a complicated question, although as “The Voyeur’s Motel” progresses, this recedes a bit, mitigated by our growing sense that the killing most likely never actually took place.

Talese doesn’t say so explicitly, but he reports finding neither police records nor coroner’s reports to match Foos’ account. The closest he comes is another unsolved homicide, “of a twenty-eight-year old Hispanic woman named Irene Cruz … [who] was found strangled to death on the morning of November 3 by housekeeping staff in a room at the Bean Hotel in Denver.”

Conflation, invention, the reassertion of Foos’ fantasy life, perhaps, taken to a larger, more existential dimension: “The Voyeur,” Foos explains in one revealing passage, “feels strong and brave in the observation laboratory, but doesn’t feel particularly overpowering anywhere else, and his strength and courage when he is not in the observation laboratory comes from the excess energy remaining from having just been there.”

What Foos is offering here is a self-portrait of pathology, which is really where “The Voyeur’s Motel” begins and ends. Or, perhaps it is a character study of a character who, like everyone, is deeply flawed.

That the book is flawed too should go without saying, although this is about more than its accuracy. Rather, Talese’s key error, I think, is his over-reliance on Foos and his diary as a central source — so much so that Foos was paid for the use of his material.

Still, I empathize. Foos’ original letter must have felt to Talese like a sort of gift: a one-of-a-kind character offering up his inner life.

There’s been a lot of talk, in wake of the Post’s revelations, about New Journalism and its fallacies, but it overlooks this larger point. New Journalism is not about making things up; it is not an attempt to fictionalize the news. Many of its key practitioners — Talese, Tom Wolfe, Joan Didion, even Hunter S. Thompson — were straight reporters first; they knew how to get the goods. What they were after were stories, narratives that would resonate with the depth of art.

“I always wanted to be a short-story writer,” Talese told me once in an interview. “To tell stories about characters, and develop them in terms of scenes.”

This, I’d suggest, is what Foos offered, a story that seemed too good not to tell. That in the end, Talese appears not to have parsed the details closely enough may have less to do with his failings, or those of journalism, than with his desire to believe.

Ulin is the author of “Sidewalking: Coming to Terms with Los Angeles,” which was shortlisted for the PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay. He is the former book editor and book critic of The Times.

::

Gay Talese

Grove Press: 240 pp., $25

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.