Column: Uber’s big report proves that the company still doesn’t understand its problems

- Share via

Uber and its fans hastened Tuesday to declare that, with the long-awaited publication of an investigation of its frat-boy office environment by former U.S. Atty. Gen. Eric Holder, the company was ready to move on. As board member Arianna Huffington told an all-hands staff meeting, “This chapter comes to an end today.”

Not so fast, Arianna.

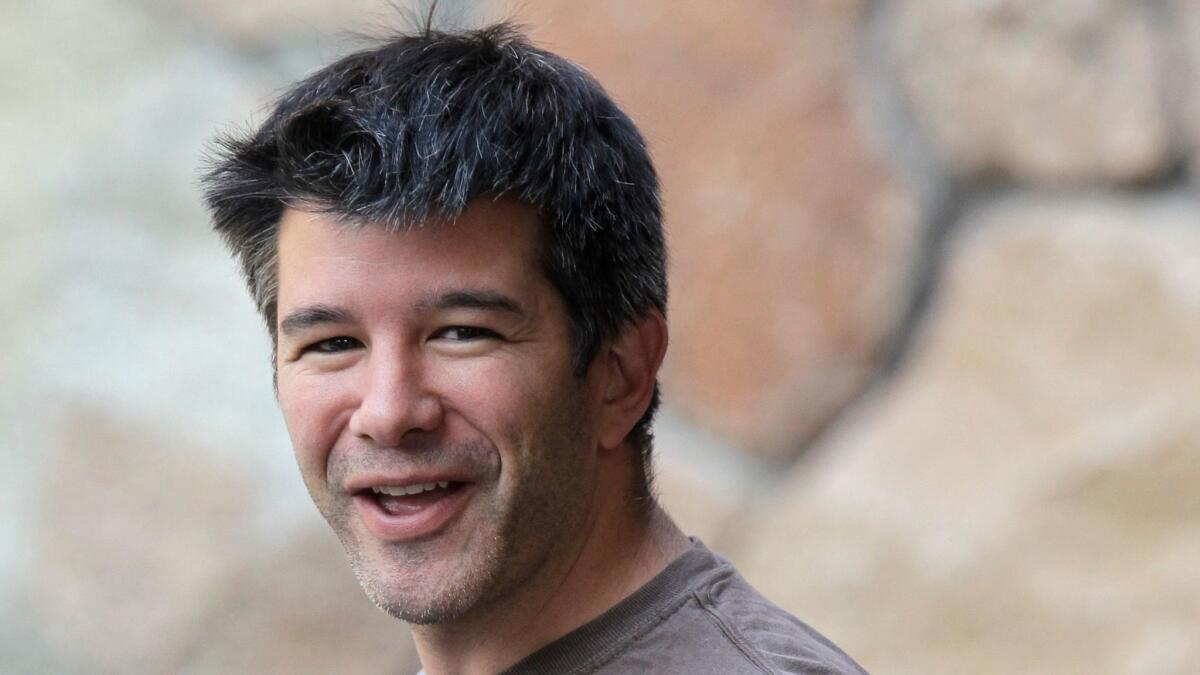

Yes, it’s true that Travis Kalanick, the Uber co-founder and CEO who is widely regarded as the sun from whom radiates the company’s bullying ethos, is taking an indefinite leave of absence. The company has fired more than 20 employees in connection with its investigation of sexual harassment claims. That process was launched in February after a former engineer, Susan Fowler, published a horrifying account of life in an organization in which sexual discrimination and harassment were accepted, even glorified, as part of the landscape.

This chapter comes to an end today.

— A very optimistic Uber board member Arianna Huffington

Yet the report by Holder and his law partner Tammy Albarran is merely a roster of 47 recommendations for fixing Uber’s dysfunctional management and employee culture. It doesn’t come close to addressing the company’s real problems.

People with a serious interest in seeing that happen are unimpressed. Fowler’s tweeted response was, “It’s all optics.” She added, “I’ve gotten nothing but aggressive hostility from them” since her account was published.

These are more fundamental than the atmosphere in the conference rooms and hallways, and raise real questions about its putative, and dubious, $70-billion valuation as a private company. They involve, first, essential questions about the economics of a company that still hasn’t demonstrated a path to profitability (see the analysis by transportation expert Hubert Horan here), but lives on the sufferance of its venture capital financiers. Uber, still a private company, has been giving the public a peek at its financials, which are swathed in red; last month it reported a loss in the first quarter of $708 million on revenue of $2.4 billion, which were both better than the previous quarter. But the company hasn’t released year-over-year comparisons, which would be more revealing.

Then there’s its relationship with its drivers who actually make its business go. There are an estimated 200,000 of them worldwide, compared with the approximately 12,000 engineers and support staff who work in Uber offices.

The latter are considered employees, the former are not. Instead, they’re classified as independent contractors. Even though Uber subjects them to its unilateral fare-setting and sets their working conditions, they pay their own expenses and have virtually no employment rights. They’re cheap labor, which may help make Uber’s economic prospects look better than they really are. As a result, says Nayantara Mehta of the National Employment Law Project, “even if the company makes all the changes it needs to make on sexual harassment, discrimination and other bad behavior, that doesn’t help the vast majority of Uber’s workforce.”

Uber’s attitude toward its drivers parallels its approach to laws and regulations, which is that it’s above them. Whenever a municipality pushes back, Uber reacts as though that’s an affront to the free enterprise — witness its attack, abetted by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, on a Seattle law granting its drivers the right to unionize. (A federal judge has temporarily placed the law on hold.)

Interestingly, the published version of the Holder-Albarran report doesn’t mention the drivers even once. According to a tape and transcript of Huffington’s remarks at Tuesday’s staff meeting, she made a single glancing reference to “our driver partners.”

None of this is encouraging, especially the Holder report’s focus on Uber’s internal policies, when the company also needs to rework its external relationships, says Catherine Bracy, executive director of the Bay Area’s TechEquity Collaborative. That includes “rethinking how it treats its drivers, taking a more collaborative approach to working with government, developing deep and trusted partnerships with communities, or developing other better business practices,” Bracy told me by email.

The Holder report’s recommendations are mostly cosmetic changes to hiring and human resources procedures, board structures, “cultural values,” etc., etc. “Increase the profile of Uber’s head of diversity,” “create an oversight committee” of the board (isn’t “oversight” the board’s whole job?), “devote adequate staff and resources to Human Resources” — these are ideas that come right off the “20 ways to make yourself a better manager” bookshelf. Except for five recommendations that involve hiring consultants, these are the sort of recommendations that come free — they cost the board almost nothing to implement, some should have been done years ago and the process of enforcement is deliberately left vague.

Only two seem to have any concrete relationship to the problem at hand. One is to bar romantic or sexual relationships between supervisors and their staffers, which might help to suppress the sexual trawling that Fowler reported, both to HR and to the public. Another is to put a cap on alcohol and drug-taking at work. (Lordy, how much of that has been going on at Uber’s San Francisco HQ? The report doesn’t say.)

Holder’s “full report” on Uber, which is how this document is billed, compares unfavorably to the last internal investigation released by a major corporation, the report on Wells Fargo’s retail banking scandal. We labeled the April 10 report a “whitewash” because its authors at the law firm Shearman & Sterling gave their clients, the board of directors, a pass. But in all other respects it left the Uber paper in the dust. Running 113 pages, compared with Uber’s 13, it laid out in painstaking detail the misdeeds of employees and the supervisors and explained how CEO John Stumpf and his management team created the conditions leading to the scandal.

The report placed blame where it belonged. Stumpf “rightfully acknowledged that he made significant mistakes and helped create the culture that resulted in sales practice abuses,” it said, specifying penalties that would cost the ex-CEO some $69 million in compensation.

That investigation gave Wells Fargo’s board and management significant information they needed to fix the bank’s problems and to do better in the future. Not the Uber report. It mentions Kalanick on only one page, in connection with a vague recommendation that the board “review and reallocate” his responsibilities. It doesn’t delve into Kalanick’s voting power over the board, which has been reported to be unassailable; the failure to acknowledge that makes its recommendations for board restructuring pointless. Even separating the CEO and chairman’s positions, a common proposal among corporate good-governance advocates, is proposed as something the board “should consider.” You can’t get much more mealy-mouthed than that.

Holder’s failure to lay out exactly what has been happening at Uber leaves the unmistakable impression of an effort to sweep the facts under the rug. Fowler’s post indicated that managers countenanced and engaged in overt sexual harassment, HR personnel were complicit, and the company threatened to fire Fowler for complaining, which is retaliation and illegal. It’s doubtful that any of this could happen without the approval, implicit or otherwise, of Kalanick and his management team.

We’re left to wonder how deeply Holder examined Kalanick’s role. We’re left to deduce it, reminding us of how the great muckraker Ida Tarbell described the Standard Oil trust: “You could argue its existence from its effects, but you could not prove it.”

In his staff message announcing his leave of absence, Kalanick still seemed to be dodging responsibility; he attributed his leave largely to his need to mourn his mother, who recently died in an accident (we don’t doubt his grief is heartfelt). He said he would take the time “to reflect, to work on myself, and to focus on building out a world-class leadership team.”

That’s not significantly different from what Kalanick often says when he and his management bros are caught doing something obnoxious or potentially illegal, a role that includes invading passengers’ privacy, deceiving driver recruits, verbally abusing an Uber driver, secretly undermining rivals and allegedly lying in a federal court proceeding. He pledges to do better, next time.

But what signs are there that Uber really is capable of change? Huffington’s statement that Uber is embarking on a “journey to being a company that always puts you, our driver partners, and our riders first” is, just yet, indistinguishable from PR. The company has been coasting on that $70-billion valuation, as though it should answer all questions about its methods and its executives’ behavior.

But Uber is worth $70 billion only as long as its venture investors are willing to pay up to be part of its club. That willingness could vanish in an instant. Unless the company grows up, fast, its value, and its future, both could be as evanescent as the tobacco cloud in a men-only cigar bar.

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email michael.hiltzik@latimes.com.

Return to Michael Hiltzik’s blog.

UPDATES:

This article was originally published at 1 p.m.