Column: Could Uber possibly be worth $70 billion? (We vote no.)

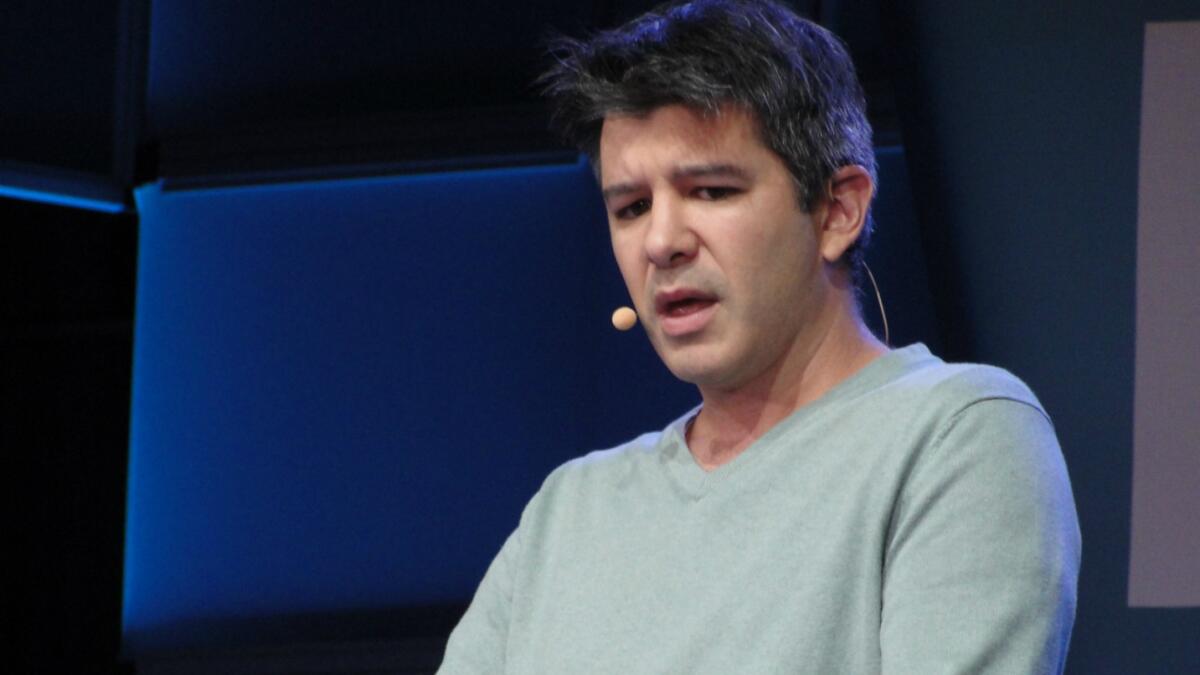

The $70-billion man? Uber CEO Travis Kalanick

In the summer of 2014, after investors bestowed $1.2 billion on the ride-hailing service Uber, some economic commentators ridiculed its then-valuation of $17 billion.

“Even smart investors can collectively make big mistakes, especially if they lose perspective,” argued finance expert Aswath Damodaran of NYU’s Stern School of Business. “The tech world is a cloistered one,” he wrote. “If history is any guide, tech geeks are just as capable of greed and irrational exuberance as bankers are.” He valued Uber then at around $6 billion, but he has since brought his number up.

Just 15 months later, Uber is reportedly on the verge of raising another $1-billion venture round in which it would be valued at up to $70 billion. Is this plausible? Among others, Timothy B. Lee of Vox says yes.

Color us skeptical.

Several threads have come together to weave the case for $70 billion. First is Uber’s unquestionably high rate of growth, which has been reported at about 300% a year. That’s based largely on its core business, which is connecting passengers and drivers via its mobile phone app, and on its frenetic pace of territorial expansion across the U.S.--more cities, and more suburbs--and into Europe and Asia. Uber and its supporters also talk about its expansion into new businesses, including carpooling and package delivery.

Then there’s the notion that Uber is poised to dominate, even monopolize, its markets. This is based partially on the “network effect” well known to high-tech experts: a network becomes exponentially more valuable as it grows, because users want to access the largest number of other users. According to this logic, both passengers and drivers will gravitate to Uber because, well, that’s where all the passengers and drivers are.

Finally there’s the “unicorn” thread, alluded to by Damodaran above. High valuations feed on themselves--if the last group of smart investors sees billions of potential in Uber, the thinking goes, who are we to scoff?

But now let’s unravel the fabric a bit.

To begin with, the financial and market arguments are based on a lot of Ifs. No one is quite sure how to measure Uber’s core market. If it’s the existing taxi business, it could be anywhere from $20 billion to $100 billion.

What’s Uber’s potential share of this market? Take a wild guess, because that’s all anyone can do. If it’s 50% of the top estimate, then Uber would capture gross revenue of $150 billion a year; if it’s 5% of the lower estimate, Uber’s revenue would be $4 billion. The real number could be anywhere within that range or out of it.

It’s proper to note that not only Uber’s market share, but its potential profit, is all conjectural. As a private company, Uber doesn’t release financial results, but the few documents that have been leaked show that it has been very unprofitable. That’s not unusual for an early-stage venture-backed company, but it does complicate the task of making projections into the limitless future. The valuation is also conjectural, since it derives from the willingness of a cadre of private investors to plunge, rather than on the collective judgment of investors in the broad public stock market.

The higher market-share estimates presuppose that Uber’s ability to move into new territories and new markets is frictionless. That’s a bad definition of Uber, which under its CEO Travis Kalanick has displayed an unerring ability to exacerbate regulatory problems wherever it goes.

In general, Uber has been able to get what it wants, after a fair amount of noise and pushback, but the process is costly and time-consuming--in San Antonio, the company had to shut down for more than six months before returning in triumph--and leaves bad feelings that could hurt the company when it needs an accommodation from City Hall (as it almost certainly will, sooner or later).

Another question is Uber’s ability to continue capturing its 20% share of its drivers’ earnings. This comes off the top of Uber fares. Drivers have to cover their own expenses such as gas, maintenance, and insurance. After all that, many discover that they’re barely earning minimum wage.

Studies point to a massive churn rate among drivers for Uber and other similar services such as Lyft, with the vast majority serving for a year or less. The reason could be that the ride-hailing services are still scaling up, so a driver force made up mostly of novices would be expected. but it could also reflect disaffection among the workers, who learn as time goes on just how little they’re earning for the effort.

That’s an opportunity for rivals to undercut Uber and a potential expense for the company, which may wind up having to bid for drivers by cutting its take below 20% or shouldering more driver expenses. Another red flag is the increasing interest of federal, state and local labor regulators in the exploitative potential of Uber’s treatment of drivers as independent contractors.

Already the California labor commissioner has ruled that Uber drivers are employees, and the National Labor Relations Board is taking a good hard look at independent-contractor claims in several industries. The NLRB doesn’t like what it sees. To the extent Uber’s valuation is based on the assumption that it can continue to collect economic rents from drivers while sticking them with all the bills, it might be way too high.

Can Uber solidify its dominant position in ride-hailing? If it can’t much of its business model begins to look shaky. As venture investor Fred Wilson observes, running at a loss to build yourself up only works “if you obtain a monopoly position in your market and you are the only game in town for your customers and suppliers.” That’s harder than people think, he says, though he doesn’t rule out that Uber might end up with most of the market, or even enough to remain dominant.

The final consideration is the venture investor market. It looks to be getting very overheated, especially in bidding for the so-called “unicorns,” which are companies valued at $1 billion or more. It may be at the stage where valuations become more and more exuberant--dangerously so.

Experts within and outside the venture funding community have been sounding the alarm about excessive valuations, as we pointed out last week. Venture capital investor Mark Suster blames an influx of “non-VC” investors such as “corporate investors, hedge funds, mutual funds and crowdsourcing” for the “less rational view of historical prices” showing up in recent valuations, though he doesn’t mention Uber. (See graphic below.)

So what’s the bottom line? NYU’s Damodaran acknowledges that he might have been too pessimistic when he placed a $6-billion valuation on Uber. He now thinks it’s worth $23.4 billion, or about one-third of its putative market value. His conclusion perfectly captures the uncertainties of valuing private venture-backed companies: “This may very well be a reflection that my vision is still too cramped to capture Uber’s possible businesses,” he writes, “but it is what it is.”

Keep up to date with the Economy Hub. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see our Facebook page, or email michael.hiltzik@latimes.com.

ALSO

Toyota shoves Volkswagen aside, takes global auto sales crown

Does playing fantasy sports amount to gambling? Debate intensifies

Climate change will be an economic disaster for rich and poor, new study says