What the new, FDA-approved 23andMe genetic health risk reports can, and can’t, tell you

- Share via

Genetic testing firm 23andMe got approval from the Food and Drug Administration last week to sell reports that show customers whether they have an increased genetic risk of developing certain diseases and conditions.

The go-ahead is the first time the federal agency has approved such direct-to-consumer genetic tests and comes about three years after the FDA warned Mountain View, Calif.-based 23andMe to stop marketing its health reports because they lacked agency authorization.

The company removed health-related results from its genetic tests after this warning, providing only ancestry information and raw genetic data without interpretation.

This time around, the FDA said its review of 23andMe’s newly authorized tests determined that the company “provided sufficient data to show that the tests are accurate,” meaning they can correctly identify genetic variants from the sample and can provide “reproducible results.”

The company said its new genetic health risk reports will be available for sale at the end of the month for $199. 23andMe also offers a test that reports only ancestry-related results for $99.

“The mission of the company is to empower individuals with this information,” said Kathy Hibbs, chief legal and regulatory officer at 23andMe, of the firm’s direct-to-consumer focus. “The belief is that everyone has the ability to make that choice about whether or not this is information that will be helpful to them.”

But there’s a lot to keep in mind about what these reports will — and won’t — tell consumers.

What it tests for

The newly approved 23andMe reports focus on specific genetic variants related to 10 diseases or conditions.

- Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency (a disorder that could cause lung disease and liver disease)

- Late-onset Alzheimer’s disease

- Celiac disease (a digestive disorder in which people can’t eat gluten)

- Early-onset primary dystonia (a movement disorder that involves issues such as muscle contractions and tremors)

- Factor XI deficiency (a blood-clotting disorder)

- Gaucher disease type 1 (an organ and tissue disorder)

- Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (a red blood cell condition)

- Hereditary hemochromatosis (an iron overload disorder)

- Hereditary thrombophilia (a blood clot disorder)

- Parkinson’s disease

How it works

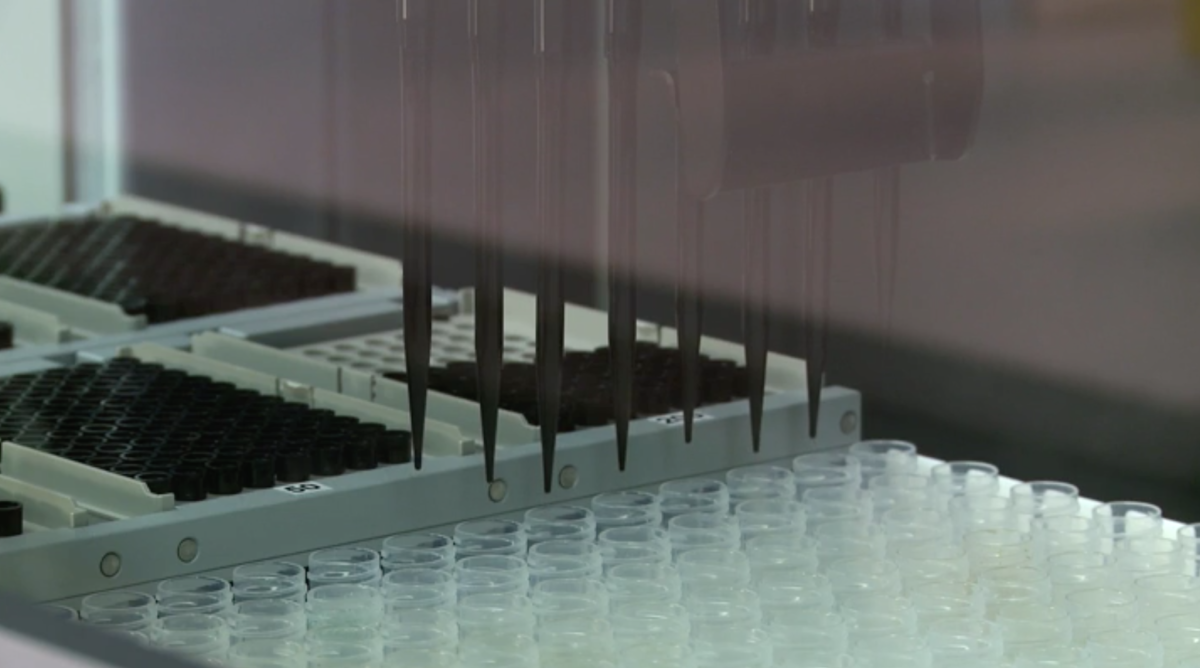

Using a saliva sample, the company looks for specific genetic variants in a customer’s DNA that are associated with increased risk of those diseases or conditions.

Customers then receive a report confirming whether they have variants associated with those conditions, or in some cases, will include the specific percentage describing lifetime risk.

These reports also include details on an individual’s ancestry, genetic traits and whether a customer is a carrier for certain diseases.

It can’t predict if you will get a specific disease

The mere instance of a variant does not mean an individual has a disease or is certain to develop it. Likewise, the absence of a variant doesn’t guarantee that someone won’t ever get that disease or condition.

The FDA was careful to make that point in its statement about the approval of the 23andMe tests.

The agency said the tests “are intended to provide genetic risk information to consumers,” but they “cannot determine a person’s overall risk of developing a disease or condition.”

“It is important that people understand that genetic risk is just one piece of the bigger puzzle,” Jeffrey Shuren, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in the statement.

One of the major worries with direct-to-consumer testing is that customers could interpret results as definitive answers, said Brent Fogel, associate professor of neurology and human genetics and director of the UCLA Neurogenetics Clinic. In the clinical world, he said, genetic risk is used only occasionally as supportive evidence.

“A concern is that people will make decisions based on these results, and they may never get the disease in question,” he said.

Genetics isn't the only factor

There are many things other than genetic variants that can contribute to the development of these diseases or conditions, including environmental or lifestyle factors. And these tests are looking only for specific variants — not all of which are associated with an increased risk of these diseases.

“Genetics isn’t destiny,” said Gregory Idos, assistant professor of clinical medicine at USC. “There’s a number of other factors that come into play when you’re looking at your susceptibility of getting a disease, and genetics is just one part of that.”

23andMe said it will explain to customers before and after purchase what the tests can and can’t confirm, and add context to the results. The FDA also has mandated that the company’s reports and pre-purchase pages include information explaining the limitations of the tests.

The reports’ relevance may vary

Not all of 23andMe’s reports will be relevant for all ethnic groups.

Many studies about genetic diseases have focused on specific populations, meaning that available data may be more relevant to people of those ethnicities.

For example, 23andMe tells customers beforehand that its report on the incidence of three variants for Gaucher disease type 1 is most relevant for people of Ashkenazi Jewish descent, while its report on Glucose-6-phosphate-dehydrogenase deficiency is more germane for people of African descent.

There could be an emotional toll

This is especially relevant for reports on variants associated with an increased risk of Parkinson’s disease or late-onset Alzheimer’s disease, both of which have no cure.

The Alzheimer’s Assn. cautions individuals to speak with a genetics counselor before and after undergoing genetic testing. Though a number of people with the disease have inherited one or two copies of the APOE-e4 variant, which is part of the 23andMe test, inheriting that form of the gene does not guarantee that a person will get Alzheimer’s.

23andMe addresses this by requiring that customers read an online disclaimer before they view results for Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s.

“This is an individual decision and not everyone necessarily is going to want this information, or they may want to wait to see that information,” said Hibbs of 23andMe.

What comes next

Idos of USC said customers should see the 23andMe reports as a steppingstone for further evaluation and discussion with a physician or genetics professional.

“It helps inform the evaluation, but you wouldn’t use it as the actual diagnostic standard test,” he said.

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.