Gig-economy giants ask California to save them from a ruling that may turn their contractors into employees

Leading gig-economy companies including Uber and Lyft are quietly lobbying California’s top Democrats to override or undermine a court ruling that could turn many of their contract workers into employees.

In April, the California Supreme Court issued a far-reaching ruling that could make it much harder for companies to claim their workforces of independent contractors are not full-fledged employees under the state’s wage laws. In the months since, business leaders have been pleading their case to state officials including members of Gov. Jerry Brown’s Cabinet, Brown’s presumed successor Gavin Newsom, and members of the state Legislature.

The business leaders are pushing to blunt the ruling’s impact, either through legislation or through executive action by the governor — moves that would reverberate across the national debate over the rights and roles of workers in the modern gig economy, and what Democrats’ posture toward tech companies should be.

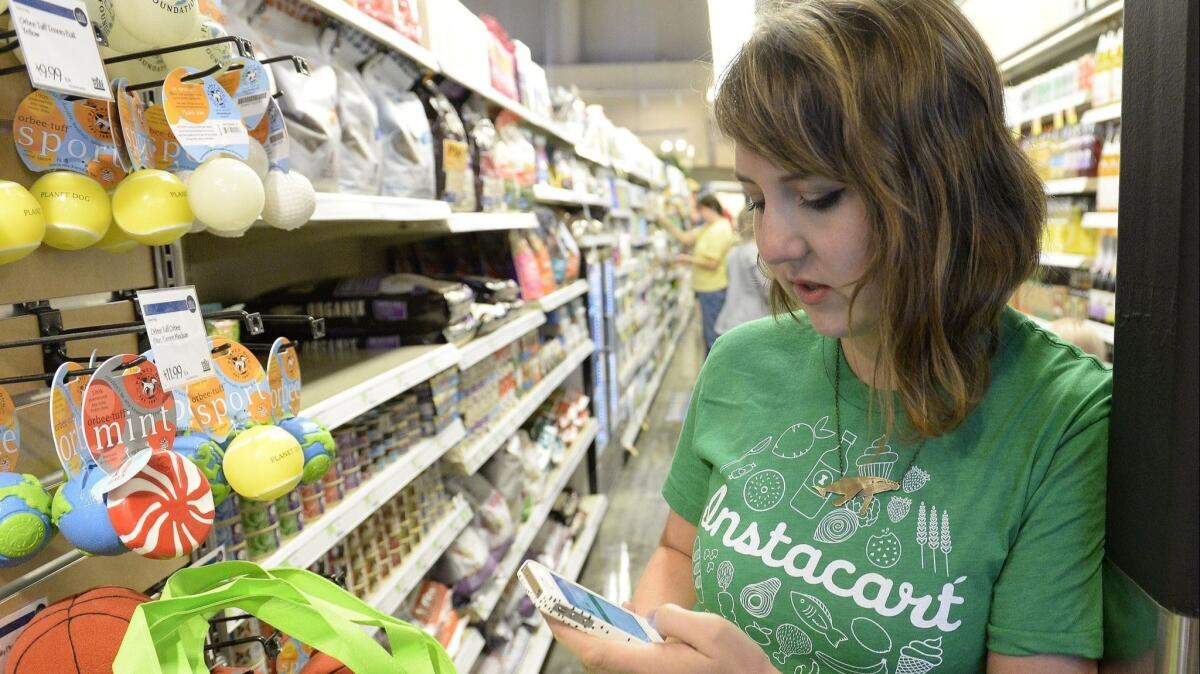

“The magnitude of this issue requires urgent leadership,” nine companies wrote in a July 23 letter reviewed by Bloomberg. The letter warns of the ruling “stifling innovation and threatening the livelihoods of millions of working Californians” and says that without political intervention it will “decimate businesses.” It was sent on behalf of Uber Technologies Inc., Lyft Inc., Instacart Inc., DoorDash Inc., Postmates Inc., TaskRabbit Inc., Square Inc., Total System Services Inc. and Handy Technologies Inc. It was addressed to the governor’s secretary of labor and Cabinet secretary.

A spokeswoman for the governor’s office declined to comment on whether Brown, whose final term ends in January, was thinking about granting the companies’ pleas.

An executive at one of the companies behind the push, speaking on condition of anonymity, said that because Brown and Newsom are both pro-tech and pro-worker, they are uniquely positioned to strike a compromise with the potential to be replicated. Forging a balance between the need for flexible, scalable work arrangements and workers’ rights shouldn’t just be left to the courts or calculated based on old models, the executive said.

Spokespeople for Lyft, Handy, TaskRabbit, Square, Postmates and Instacart declined to comment on the companies’ lobbying efforts. DoorDash did not respond to inquiries. Spokespeople for Total System Services and Uber referred requests for comment to the California Chamber of Commerce, which has been an outspoken opponent of the new requirements. “If you have a business model that doesn’t lend itself to the strict structure that an employer-employee relationship dictates,” said the chamber’s president and chief executive, Allan Zaremberg, then the ruling “puts you in a situation that it’s almost impossible to continue your business model.”

Zaremberg declined to comment on the prospect of executive action from the governor’s office, but said the chamber aims to get a legislative fix introduced and passed by the state’s Assembly and Senate before the legislative session closes at the end of the month. Without it, he said, workers and companies alike will be “hamstrung,” and whole sectors of California’s economy could be in jeopardy. “People depend very much now on an on-demand economy,” said Zaremberg. “In the worst-case scenario, it isn’t a viable business model anymore.”

The California Labor Federation pledged Sunday to resist the efforts to suspend or reverse the ruling. “With income inequality at an all-time high and millions of working families struggling to survive in this unfair economy, why would our state’s leaders intervene to protect big corporations from paying the wages owed to their workers?” said the group’s legislative director, Caitlin Vega.

Federal and California laws entitle employees to a suite of rights including minimum wage, overtime pay, protection from sexual harassment, payroll tax contributions from employers and the chance to win collective bargaining. Those perks don’t extend to independent contractors, a category for workers with greater autonomy to choose the terms of their work. The boundary between an employee and a contractor can be fuzzy, though, and is defined differently under different laws. The question of who gets employee protections has been hotly contested in a slew of government agency proceedings and lawsuits around the country, frequently targeting app-based sectors such as ride-hailing as well as older industries such as trucking and healthcare.

The April ruling in the California case — Dynamex Operations West Inc. vs. Superior Court of Los Angeles — established what’s sometimes called an “ABC” test for enforcement of the state’s wage laws. Among the key elements of the new standard, which is more stringent than most states’ or the federal government’s, is the determination that people are employees of a company unless they are conducting “work that is outside the usual course” of the company’s business. For businesses whose core capacity is delivering a service to customers via an army of workers classified as independent contractors, that could be a challenging test to pass.

The court ruling applied only to California, but companies worry that, along with upending their operations in the nation’s most populous state, it could be a harbinger elsewhere. The week after the Dynamex decision, Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) introduced a bill — backed by a handful of fellow potential contenders for the Democratic Party’s 2020 presidential nomination — that would make an equivalent ABC test the standard for federal labor laws, like who has the right to unionize.

Rather than treating that as an idle threat, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce has already been lobbying congressional offices about the bill, according to federal disclosures. In meetings with U.S. Senate staff, business leaders have been emphasizing the downsides of Dynamex’s ABC test, according to a person familiar with the conversations. Getting Democratically controlled California to pump the brakes on its new court-decreed standard could also have a significant impact on national-level discussions.

In their letter to Brown, the businesses floated ways to curtail the ruling’s influence. Those included issuing an executive order barring state agencies from implementing the ABC test, reviving a defunct state commission that could amend it, and passing legislation that would suspend it. The companies cite an estimate by the pro-free-market research group R Street Institute that more than 300,000 California workers could be newly considered employees rather than independent contractors due to the ruling. Once the imminent damage from Dynamex is averted, the companies say in the letter, there could be “a robust legislative discussion about how we can collectively invest to protect worker voices and benefits” in the new economy, as well as a “balanced test” for who is an employee.

The companies have also met with the governor’s office to plead their case, according to a person familiar with the matter who asked not to be identified because the meetings were private. And they have discussed the issue with the Democrats who lead the state’s Assembly and Senate and with Newsom. Spokespeople for Newsom, Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon and Senate President Pro Tempore Toni Atkins declined to comment.

Gig-economy start-ups aren’t the only companies concerned. The “I’m Independent” Coalition, a project of the California Chamber of Commerce devoted to opposing the ABC test, also counts the Internet Assn. as a backer. The association’s members include Google, Amazon and Facebook, all of which also hire contractors.

Read more: Inside Google’s shadow workforce of contract laborers »

“The internet industry is concerned about the implications of the Dynamex ruling and its potential to jeopardize internet-enabled, freelance work,” the association’s California government affairs director, Kevin McKinley, said in an emailed statement.

The “I’m Independent” Coalition also includes the state associations representing restaurants, retailers, publishers, hospitals, shopping centers, child-care providers, farms, grape growers, manufacturers, trucking, taxis, ambulances and insurers. The coalition has gathered statements from workers about why they prefer to be classified as contractors, and is working to mobilize some for an Aug. 15 rally at the state Capitol in Sacramento.

Companies are also urging their own workers to join the cause. On Thursday, DoorDash sent an email to its “California Dashers” telling them that the Dynamex ruling threatens their “flexibility to choose when, where and how you want to work,” and providing a web tool to send their state legislators a message asking them “to help protect my freedom to choose the way I work.”

Shannon Liss-Riordan, an attorney who represents a worker suing DoorDash, responded by filing a motion Friday in federal court asking a judge to enjoin the company from “engaging in further coercive and misleading communications” that she alleged encourage workers covered by her putative class-action lawsuit to “undermine their claims” in the case. DoorDash did not respond to inquiries.

Workers’ advocates have argued that responsible companies should welcome the clarity of the court’s April ruling. “It’s been a bit of a free-for-all, particularly in California, where a whole economy of companies has risen up in recent years saying that they can build their workforce off of workers that don’t have any employment protections,” said Liss-Riordan, who also represents workers currently suing other gig-economy companies including Uber, Lyft and Postmates over alleged denials of employee rights (the companies have denied wrongdoing).

Labor advocates say there’s no reason for California to water down workers’ rights. “These companies continue to have choices about their business model,” union leaders from the state’s building trades, Teamsters union affiliates and AFL-CIO chapter told Brown and legislative leaders in a July letter reviewed by Bloomberg. “They can convert workers to employees and retain control over their work rules and their rates. Or they can contract with true independent contractors. The only thing they can’t do after Dynamex is have their cake and eat it too.”

Eidelson writes for Bloomberg.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.