Orange County, failing ‘housing scorecard,’ urged to build more homes

Long a land of plenty for home buyers and builders alike, Orange County is running out of room. If it hopes to keep growing, the vast suburbia needs to change its ways.

That’s the thrust of a new report out Tuesday from the influential Orange County Business Council, which estimated that the county of 3.1 million already faces a shortfall of 62,000 homes and apartments to meet the needs of its workforce.

If job and housing projections hold true, that shortfall will deepen to 100,000 by 2040, the report says, making it harder for young families to find a place to live and for businesses to find high-quality employees.

“We already lose more than we should,” said Wallace Walrod, the Business Council’s chief economic advisor and author of the report. “This has long-term consequences for our economic competitiveness.”

The study, the council’s “Housing Scorecard,” is the latest in a string of calls lately to create more housing in Southern California, which is among the nation’s least-affordable housing markets.

Late last year, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti announced a goal of adding 100,000 homes in the city by 2021. Last month, the state’s nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office issued a report saying 100,000 or more homes a year — mostly in coastal regions — are needed to keep already sky-high housing costs from dragging down California’s economy.

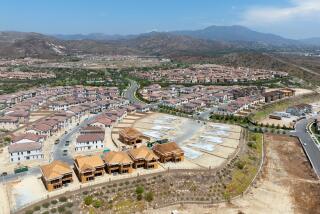

In Orange County, where home buyers have flocked for decades seeking a slice of the suburban life, the call to build more comes with a twist. There’s no longer enough open land to keep building vast tracts of single-family homes, the report says. The future lives in a town house.

“The era of big master-planned communities is not quite over, but it’s ending,” Walrod said. “The kind of development that’s going on in Orange County is fundamentally changing. It’s going to be more infill, mixed-use, high-density development.”

But in many parts of Southern California, high-density housing remains a tough sell. Orange County is no exception. The Business Council’s report cites environmental regulations and lawsuits as well as neighborhood opposition as two of the chief hurdles blocking more construction.

Winning local approvals for an “infill” project — typically denser redevelopment in an existing neighborhood — can take 18 months to two years, said Scott Laurie, chief executive of Olson Homes, a Seal Beach-based builder that specializes in those sort of projects. Picking the right site, winning over the neighbors and designing a project that makes sense economically all take time too.

“This is not the type of building that you see in outlying areas,” Laurie said. “This is a different business.”

But, he said, there is high demand. Olson Homes just sold out a development in Fullerton and is about to launch sales on 45 town houses in Huntington Beach, with strong early interest. Many buyers are willing to make trade-offs for a manageable commute and a good neighborhood.

“They’ll say, ‘I may not have a big house on a big lot,’” he said. “But I’m 15 minutes from work, I can walk to things and I have great schools.”

That’s the sort of thinking that led Roderick and Toni Ashford to The Groves, a new KB Home development in Fullerton. The couple recently relocated from Washington state for work, and were looking for someplace close to his job and their children’s school in Long Beach.

They looked at single-family homes in Orange County and around Long Beach, but soon tossed that idea aside. Everything was too expensive. Then they found a 2,100-square-foot town house in Fullerton for $540,000. They took it.

“It’s very expensive everywhere,” Toni Ashford said. “This is a good price for us.”

For some, the lure of a big house at a relatively low cost is still worth commuting from Riverside County, where the median home price in February was roughly half of Orange County’s, according to CoreLogic Dataquick. Maria Lopez, a real estate agent with Redfin in Chino and Corona, has seen a noticeable uptick lately of priced-out buyers moving east.

“For what you pay in Anaheim Hills or Yorba Linda, you can cross the 71 [Freeway] into Corona and get the same size property for a couple of hundred thousand dollars less,” she said. “People will make that trade for an extra 15 minutes’ drive.”

In the long run, though, that commute poses a big challenge for Orange County, said Esmael Adibi, an economist at Chapman University. If companies can’t find the workers they need, they’ll eventually move to where the people are, be that the Inland Empire or all the way to Texas. With an aging population, places like Orange County need to make sure they’ve got room to house the next generation.

“Everything else being equal, housing costs are a major, major factor to slowing down growth,” Adibi said.

And that’s what has the Business Council worried.

Orange County has already seen its age 25-to-34 population shrink 7% over the last 15 years, Walrod said. Nearly 40% of Orange County workers commute more than an hour a day. And at current trends, in 10 years half of the county’s homeowners will be over age 65.

If all that keeps up, Walrod said, Orange County won’t have the workers it needs to keep growing, unless it builds enough places for them all to live.

“If you look out five, 10, 20 years, the picture really becomes clear,” he said. Housing “can either be a huge positive for the area, or it can be our Achilles’ heel.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.