Boeing manager tried to halt 737 Max production before fatal crashes, lawmaker says

A Boeing Co. manager sought to halt production of the 737 Max over safety concerns before the first of two fatal crashes that led to the jet’s worldwide grounding, a top House lawmaker charged Tuesday.

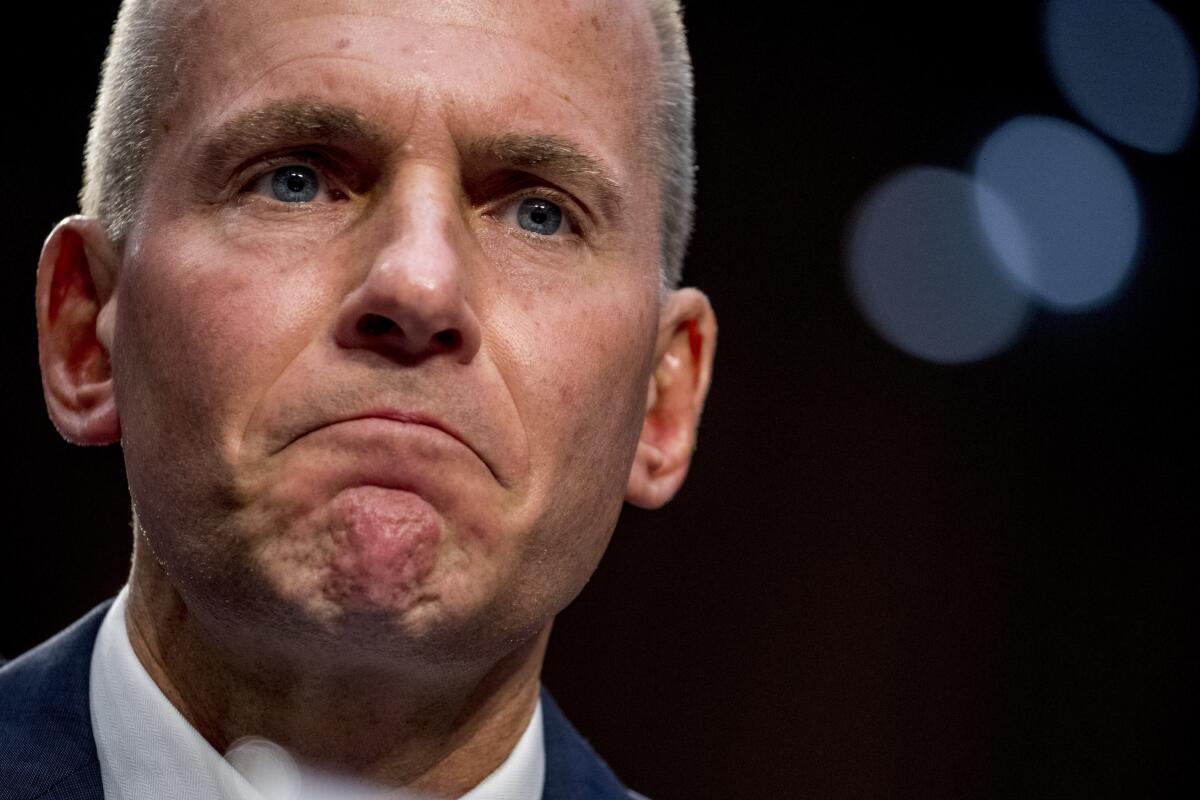

Rep. Peter DeFazio (D-Ore.), the chairman of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, included the new allegations in a prepared statement for a hearing Wednesday at which Boeing Chief Executive Dennis Muilenburg will testify. The CEO testified Tuesday before a Senate committee about the 737 Max, which has been banned from flying since March.

“We now know of at least one case where a Boeing manager implored the then-vice president and general manager of the 737 program to shut down the 737 Max production line because of safety concerns, several months before the Lion Air crash in October 2018,” DeFazio said in his prepared opening statement, which was released by the committee.

DeFazio’s accusations pile pressure on Muilenburg as the embattled CEO prepares for a second day of grilling on Capitol Hill. Muilenburg is fighting to save his job amid heightened scrutiny from Boeing directors. He’s also trying to salvage the U.S. industrial titan’s reputation after months of bruising disclosures about shortcomings in the design and certification of the Max, Boeing’s best-selling jet. The crashes — one in Indonesia last October and one in Ethiopia in March — killed everyone aboard the two planes, a total of 346 people.

Even as senators peppered Muilenburg with blistering questions, Boeing stock rose as investors seemed convinced that the testimony wouldn’t impede the Federal Aviation Administration’s review of whether the grounded Max can safely resume commercial flight after a redesign of flight-control software. The shares climbed 2.4% to close at $348.93, the third-best performance in the Dow Jones industrial average.

DeFazio didn’t detail the nature of the safety concerns raised by the Boeing manager or how the company responded. The Chicago-based plane maker didn’t immediately comment.

At least one whistleblower also told the committee that the company sacrificed safety for cost savings, DeFazio wrote. Boeing also considered adding a more robust alerting system for the feature involved in two crashes before ultimately shelving the idea, according to DeFazio.

“We may never know what key steps could have been taken that would have altered the fate of those flights, but we do know that a variety of decisions could have made those planes safer and perhaps saved the lives of those on board,” DeFazio said.

DeFazio’s statement is the first detailed look at findings by the House committee, which is conducting what the chairman called the “most extensive and important” investigation he’s seen during his time on the panel.

Some of the statement was crafted as questions for Muilenburg.

“There are areas we are exploring that remain murky, and we need to bring clarity to those issues,” DeFazio said. “But there is a lot we have learned over the past seven months, and we expect you to answer a number of questions to improve our understanding of what happened and why.”

A set of stairs may have never caused so much trouble in an aircraft.

About 20 relatives of crash victims attended Tuesday’s hearing before the Senate Transportation Committee, whose chairman, Sen. Roger Wicker (R-Miss.) opened the session by promising the inquiry would get to the bottom of what went wrong.

“Both of these accidents were entirely avoidable,” Wicker said. “We cannot fathom the pain experienced by the families of those 346 souls who were lost.”

A flight-safety feature known as MCAS, designed to lower the nose of the plane in some conditions, was activated in both fatal crashes as a result of a malfunction, and in both cases, pilots didn’t respond and lost control.

Boeing had successfully lobbied regulators to keep any explanation of the feature from pilot manuals and training. “Those pilots never had a chance,” said Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.). Passengers “never had a chance. They were in flying coffins as a result of Boeing deciding that it was going to conceal MCAS from the pilots.”

Muilenburg said Boeing had always trained pilots to respond to the effect caused by an MCAS failure — a condition called runaway trim — which also can be caused by other problems.

Muilenburg apologized directly to victims’ family members, many of whom had brought large photos of their loved ones, and said Boeing is committed to safety and to learning from the crashes.

We’ve been challenged and changed by these accidents. We’ve made mistakes and we got some things wrong,” Muilenburg said.

Boeing hopes that by year’s end, it will win the FAA’s approval to return the plane to flight. The agency is also coming under scrutiny for relying on Boeing employees to perform some certification tests and inspections. It’s an approach the FAA has followed for many years.

“We need to know if Boeing and the FAA rushed to certify the Max,” Wicker said.

The committee didn’t get an answer to that question.

Muilenburg sometimes fumbled his explanations of embarrassing internal messages and of the manufacturer’s close ties to U.S. regulators. And he didn’t rattle off changes made to improve safety with the aplomb and detail with which General Motors Co. CEO Mary Barra once addressed faulty ignition issues before lawmakers, said Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, senior associate dean for leadership studies at the Yale School of Management.

But Muilenburg avoided other traps, such as sounding defensive, dismissive or arrogant, Sonnenfeld said.

“I think he came across as genuine and contrite,” he said. “He wasn’t elegant, but he wasn’t arrogant.”

After the hearing, Muilenburg held a charged meeting with a group of victims’ relatives, his first such direct interaction since the accidents.

“It was very emotional in there to have the CEO of the company that had a substantial part in killing my daughter, Samya Rose Stumo,” Michael Stumo said in a news conference after the meeting.

“But he was there, he heard, and he expressed his sorrow appropriately, and expressed a desire to change the culture of the company to make it better,” Stumo said, vowing that the group would continue to press for legislation to change aviation safety rules.

The Associated Press was used in compiling this report.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.