Column: Uber and Lyft increase traffic and pollution. Why do cities let it happen?

Uber and Lyft owe their great popularity to customer-friendly features such as short waiting times, low fares and the convenience of hailing a cab and paying by smartphone.

But with these virtues come multiple drawbacks, which state and local officials are struggling to deal with.

Recent studies have found that when Uber and Lyft enter a market, their fleets are more polluting than autos on average, contribute to more traffic congestion particularly in the central cities, undermine public transit systems and devastate the local taxi industry. The ride-hailing firms say that some studies have come to opposite conclusions or that those impacts are outweighed by the advantages they bring to local transportation markets.

We’re on the brink of the whole industry collapsing because there’s so little revenue.

— Leon Slomovic, veteran taxi driver

Yet government regulators have been hard-pressed to combat these problems, partially because they’ve tied their own hands.

“We’ve let them do what they want,” Paul Koretz, a Los Angeles councilman who has been concerned about the firms’ effect on taxi services, told me.

The issue is especially acute in California, where the Public Utilities Commission took the initiative in 2013 of carving out a separate regulatory regime for the ride-hailing industry, categorized as “transportation network companies.”

That forestalled local initiatives to equalize ride-hailing regulations with those of taxis. Cabdrivers are generally subject to more stringent background checks and vehicle inspections than ride-hailing drivers.

But the PUC has had difficulty overseeing the new industry, as commission President Michael Picker, who took office after the PUC’s action, later acknowledged, calling ride-hail regulation not “something we can do effectively.”

Let’s take a look at the key impacts confronting state and local officials when Uber, Lyft and other such services come into their markets.

Uber, Lyft and Doordash will spend $90 million to undercut a California employment law.

Start with congestion. A study by Gregory D. Erhardt and colleagues at the University of Kentucky in conjunction with the city of San Francisco found that average speed within the city decreased to 22.2 miles per hour in 2016 from 25.6 mph in 2010, and that “vehicle hours of delay” increased by 63% in that period.

Although there were myriad contributors to the change, including population and employment growth, the researchers blamed it chiefly on the entry of the ride-sharing firms. The worst increase in congestion occurred in the central business district, where Uber, Lyft and other services were prevalent.

Most trips on those services “are adding new cars to the road,” they found. Most ride-hail drivers, moreover, lived outside San Francisco, so their commute into the city was another factor.

A similar trend showed up in New York City, where Uber, Lyft and other app-based services added 50,000 vehicles to the roads, according to a study by transportation consultant Bruce Schaller.

The arrival of ride-hailing services in a city is generally accompanied by a decline in mass transit. Studies of public transit ridership in major cities published last year by Erhardt’s team concluded that once the services arrive in a market, rail ridership declines by an average of 1.3% and bus ridership by 1.7%.

The effect “builds with each passing year,” the researchers found, to the point where even significant expansion of transit systems isn’t enough to reverse the decline; after eight years, transit systems would have to expand service by 25% just to keep ridership from falling. “Transit agencies are fighting an uphill battle,” they wrote.

In Los Angeles, a rise in transit ridership that began in 2004 flattened out or reversed after Uber entered the L.A. market in 2012, especially in rail. (Bus ridership had begun to decline as early as 2007.) Total ridership declined more than 22% from its peak in 2013 through 2019, from 478.1 million riders to 370.5 million, according to the L.A. County Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

A 2018 study for the Southern California Assn. of Governments called the companies “a plausible culprit in transit’s decline” in the region, though not the sole culprit.

The ride-hailing companies maintain that their services actually can help local transit networks by ferrying passengers to transit depots. Uber and Lyft have begun to add maps of transit stops to their apps, ostensibly to help their passengers coordinate their car trips with transit schedules. Lyft has rolled out a limited program from Feb. 14 through April 30 offering discounts or credits for shared rides to L.A. Metro rail stations at rush hour.

The companies generally argue that their contribution to congestion is relatively slight. “While ridesharing is part of congestion, we believe our impact is on the margin of a vastly larger contribution from private vehicle use,” Uber told me by email.

Uber’s first-quarter earnings report released Thursday — its first since the ride-hailing company went public on May 10 — disclosed more than the financial condition of the company.

The company also said it believes that “stronger investments in public transportation can help ease traffic. If we can get people out of using their personal cars and into public transit or other active modes of transportation like bikes and scooters, we believe ridesharing can be an effective complement that helps ensure travelers always have means to get from point A to B.”

Lyft echoed those sentiments. “We remain focused on making car ownership optional, supporting transit, investing in shared rides, adding bikes and scooters, and partnering with cities on thoughtful policy solutions,” spokeswoman Campbell Matthews told me.

But Uber also has made clear that it views itself as an alternative to public transit. In the registration statement it filed prior to its 2019 initial public stock offering, the firm stated that it competes with “traditional transportation services, including taxicab companies and taxi-hailing services ... and public transportation.”

Uber expressed the ambition to “rapidly scale our network in new cities by attracting consumers to our platform and away from personal vehicles or public transportation.”

Lyft, which has long sought to frame itself as the kinder, gentler ride-hailing service in contrast to Uber, downplayed the competitive aspect of its service in the registration statement for its 2019 IPO and played up its potential to enhance “multimodal” transportation.

Pollution is another issue, caused mainly by idling and cruising by ride-hail vehicles without a passenger. The California Air Resources Board calculates that even though vehicles used for ride-sharing tend to be newer and are mostly light cars rather than gas-guzzling SUVs, their emissions are 50% higher than California vehicles per passenger mile traveled.

Among the key factors are that the ride-share cars have lower average passenger occupancy than the statewide fleet, and spend nearly 40% of their time on the road without a passenger in the car — “deadhead miles,” in industry parlance.

By far the most immediate impact of the ride-hailing firms is on taxis. “We’re on the brink of the whole industry collapsing because there’s so little revenue,” says Leon Slomovic, 63, who has been a taxi driver since 2001 and is the spokesman for the Taxi Workers Alliance of Los Angeles.

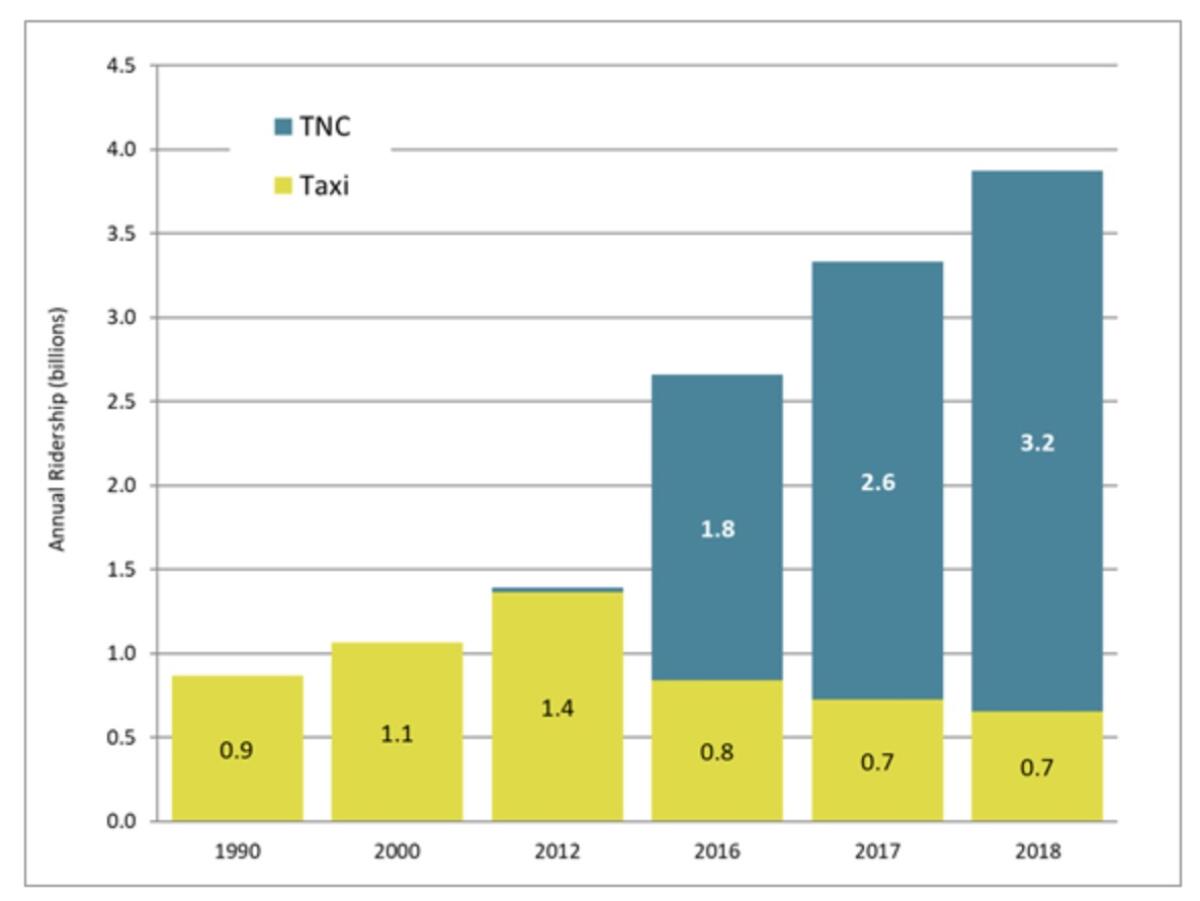

Taxi ridership in the city has declined by an estimated 77% since the advent of ride-sharing, according to a Los Angeles Dept. of Transportation study (Arguably the taxi industry was ripe for competition, saddled as it was with a reputation for poor service.)

As the ride-hail apps made inroads into the Los Angeles market, local taxi drivers spent more time at LAX, where demand for their services remained robust. “Over the last five years, that became a crutch for the entire industry,” says Eric Spiegelman, chairman of the Los Angeles Taxicab Commission.

The crutch was kicked out from under the cabbies in last year, when the airport’s management ended curbside pickups of passengers inside the terminal area and moved the taxis and ride-hail cars to LAXit, a centralized pickup zone next to the Southwest Airlines terminal.

The move aimed to alleviate crowding caused by construction that had taken away two traffic lanes in the terminal access road, but the change eliminated the one significant advantage taxis had over Uber and Lyft — the ability to serve passengers hailing from curbside.

The long-anticipated initial public offering filing Thursday by uber-unicorn Uber, the big ride-sharing company, evokes two principles.

“I told LAX, ‘You’re putting an end to the taxi industry in Los Angeles,’” Koretz says. “I didn’t get a peep in response.”

Koretz noted that several classes of passengers find shuttling to LAXit unduly burdensome, including disabled passengers and those traveling with small children. The airport’s management has been considering whether to allow taxis to resume curbside pickups at selected terminals, including the Tom Bradley International Terminal, but the idea is still preliminary and no decision has been made.

The drawbacks from the growth of ride-sharing firms may seem remote to passengers reveling in the low cost and high convenience of Uber and Lyft, but they’re ignored at our peril. The Air Resources Board warns that the rapid expansion of ride-sharing will make their contribution to greenhouse gas emission ever more significant in the future, which “necessitates formulation of immediate policies.” ARB says that increasing occupancy through shared rides and decreasing deadhead miles have the most potential to reduce the services’ emissions.

New York and Chicago have implemented congestion fees to reduce traffic in their central cities; New York also has imposed a first-in-the-nation cap on new permits for ride-hail vehicles, while also mandating a minimum wage for their drivers. Taken together, those steps appear to have alleviated congestion, reduced the number of trips, and improved earnings for ride-hail and taxi drivers alike. They may not all be possible in other cities except those with strong public transit systems such as San Francisco, Schaller says.

Addressing the taxi crisis may be harder. To a certain extent, the industry itself has contributed to its problems. “They haven’t tried any kind of innovative thinking in the last six years to confront this threat head-on,” says Spiegelman. Some taxi co-ops have tried online apps similar to those of Uber and Lyft, but not much more.

In some cities, taxis have acquired a reputation for crumminess that may be hard to overturn. Even in New York, where taxis are plentiful and Uber and Lyft don’t enjoy a significant price advantage over them, “customers are still voting with their feet” and choosing the ride-hail services, Schaller says. “Taxis are not competing well on service.” Taxi services long have had a reputation for passing minority passengers by, while Lyft and Uber are thought to be less prone to discrimination.

Some experts believe that reducing taxi fares might make them more competitive. That’s an option explored by Christopher S. Tang of UCLA’s Anderson School of Business, who based his research partially on the impact of the ride-sharing service DiDi in China. He also suggests that public transit systems, taxi services, and the ride-hail firms work out single-ticket arrangements allowing passengers to reach their destinations via a combination of travel modes. “That could be a win-win,” he told me.

Slomovic is skeptical that taxi fares could come down enough in L.A. to compete with Uber and Lyft, without reducing cabdrivers’ income beyond unsustainable levels. Ride-hail fares are destined to rise as the companies reach for profitability. But they’re still capable of subsidizing fares with the billions of dollars they’ve raised from venture investors and stock sales. A taxi cost index used by the L.A. Taxicab Commission to set fares has risen over time, but taxi co-ops have asked the commission to avoid raising fares — they’ve been kept at $2.70 per mile for the last 10 years, but that’s still much higher than Uber or Lyft fares.

Saving the taxi industry is crucial. For one thing, they provide competition for the ride-hailing firms. “If Uber can squeeze out the taxis, they can become a more effective monopoly and raise their prices,” says Tang. “That may not be a good idea from the public’s perspective.”

As a regulated industry, taxis perform services that Uber and Lyft are free to shun. In Los Angeles, which issues franchises to taxi firms, they’re required to cover underserved communities such as low-income neighborhoods. Passengers who can’t use app-based services because they don’t have access to smartphones or don’t have bank accounts or credit cards that can be used for payment often rely on taxis instead, because they can pay with cash.

Uber, Lyft and services like them have been a boon for millions of passengers. But they’re not good for everybody.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.